![]()

Chapter 1

It Matters How Students Learn Mathematics

Berinderjeet KAUR

This introductory chapter details the emphasis of the 2012 school mathematics curriculum in Singapore and also provides an overview of the chapters in the book. The chapters centre around three main areas: fundamentals for active and motivated learning, learning experiences for developing mathematical processes, and the use of ICT tools for learning. It ends with some concluding thoughts that readers may want to be cognizant of while reading the book and also using it for reference and further work.

1 Introduction

This yearbook of the Association of Mathematics Educators (AME) in Singapore focuses on Learning Experiences to Promote Mathematics Learning. Like all of the past yearbooks, Mathematical Problem Solving (Kaur, Yeap, & Kapur, 2009), Mathematical Applications and Modelling (Kaur & Dindyal, 2010), Assessment in the Mathematics Classroom (Kaur & Wong, 2011), Reasoning, Communication and Connections in Mathematics (Kaur & Toh, 2012) and Nurturing Reflective Leaners in Mathematics (Kaur, 2013), the theme of this book is also shaped by the foci of the school mathematics curriculum developed by the Ministry of Education (MOE) and the needs of mathematics teachers in Singapore schools.

The 2012 syllabus for mathematics in Singapore schools (MOE, 2012a; 2012b) places heightened emphasis on the role of learning experiences for mathematics learning. It states that:

Learning mathematics is more than just learning concepts and skills. Equally important are the cognitive and metacognitive process skills. These processes are learned through carefully constructed learning experiences. For example, to encourage students to be inquisitive, the learning experiences must include opportunities where students discover mathematical results on their own. To support the development of collaborative and communication skills, students must be given opportunities to work together on a problem and present their ideas using appropriate mathematical language and methods. To develop habits of self-directed learning, students must be given opportunities to set learning goals and work towards them purposefully. A classroom rich with these opportunities, will provide the platform for students to develop 21st century competencies (MOE, 2012a, p. 20; 2012b, p. 20).

2 Learning Experiences in the Mathematics Syllabuses

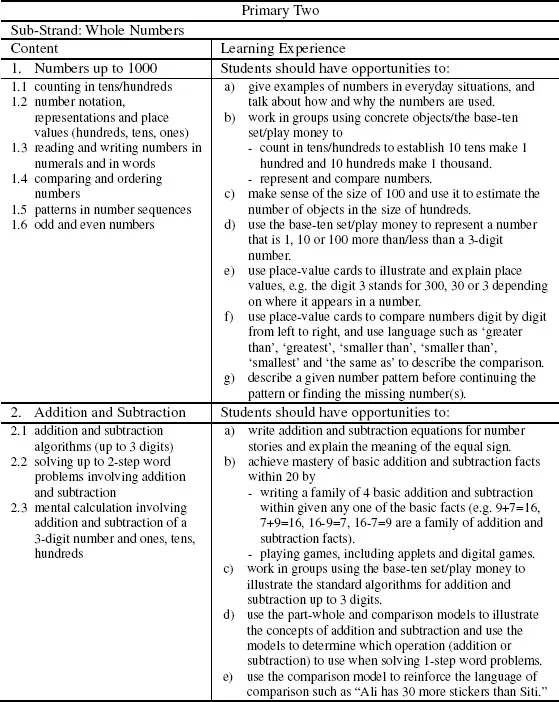

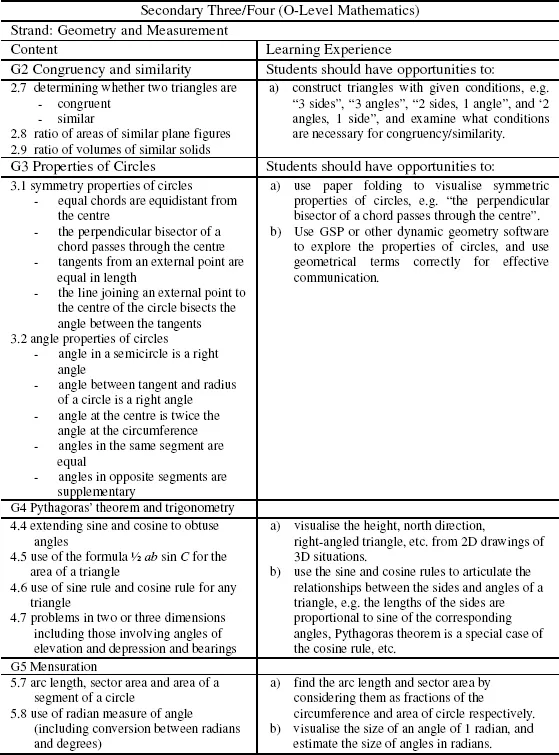

In the 2012 mathematics syllabuses for schools in Singapore “learning experiences are stated in the mathematics syllabuses to influence the ways teachers teach and students learn so that the curriculum objectives can be achieved” (MOE, 2012a, p. 20; 2012b, p. 20). Figure 1 shows an excerpt from the primary school syllabus and Figure 2 shows an excerpt from the secondary school syllabus. From both figures, it is apparent that statements expressed in the form “students should have the opportunities to …” focus teachers on the student-centric aspect of learning mathematics. The statements describe actions that would allow students to i) engage in co-creation of knowledge ii) make sense of the knowledge they acquired and iii) work collaboratively and communicate their reasoning using mathematical vocabulary.

The syllabuses, an intended curriculum, serve as a guide for teachers to undertake school-based curriculum innovations and customisations in line with the broad aims of mathematics education in Singapore. The aims are to acquire and apply mathematical concepts and skills; develop cognitive and metacognitive skills through a mathematical approach to problem solving; and develop positive attitudes towards mathematics (MOE, 2012a, p. 7; 2012b, p. 7).

Figure 1: An excerpt from the primary mathematics syllabus (MOE, 2012a, p. 37)

Figure 2: An excerpt from the secondary mathematics syllabus (MOE, 2012b, pp. 57-58)

In addition the syllabus documents outline three principles of mathematics teaching and three phases of mathematics learning in the classrooms. The three principles of teaching are as follows:

Principle 1 – Teaching is for learning; learning is for understanding; understanding is for reasoning and applying and, ultimately problem solving.

Principle 2 – Teaching should build on students’ knowledge; take cognizance of students’ interests and experiences; and engage them in active and reflective learning.

Principle 3 – Teaching should connect learning to the real world, harness ICT tools and emphasise 21st century competencies (MOE, 2012a, p. 23; 2012b, p. 21).

The three phases of mathematics learning in the classrooms are as follows:

Phase I – Readiness

Student readiness to learn is vital to learning success. In the readiness phase of learning, teachers prepare students so that they are ready to learn. This requires considerations of prior knowledge, motivating contexts, and learning environment.

Phase II – Engagement

This is the main phase of learning where teachers use a repertoire of pedagogies to engage students in learning new concepts and skills. Three pedagogical approaches, activity-based learning, teacher-directed inquiry, and direct instruction, form the spine that supports most of the mathematics instruction in the classroom. They are not mutually exclusive and could be used in different parts of a lesson or unit. For example, the lesson or unit could start with an activity, followed by teacher-led inquiry and end with direct instruction.

Phase III – Mastery

This is the final phase of learning where teachers help students consolidate and extend their learning. The mastery approaches include: motivated practice, reflective review and extended learning. (MOE, 2012a, p. 24-27; 2012b, pp. 22-25).

The learning principles and phases of learning in the Singapore school mathematics syllabus documents signal very clearly the need for teachers to engage their students in active learning and learning for understanding in contexts that are motivating and help them develop 21st century competencies. To address the challenge faced by teachers, in Singapore schools, in harnessing appropriate learning experiences to engage students in their learning of mathematics the theme of the 2013 conference for teachers, jointly organised by the Association of Mathematics Educators (AME) and the Singapore Mathematical Society (SMS), was appropriately Learning Experiences to Promote Mathematics Learning.

The following 13 peer-reviewed chapters resulted from the keynote lectures delivered and invited workshops conducted during the conference. The authors of the chapters were asked to focus on evidence-based practices that school teachers can experiment in their lessons to bring about meaningful learning outcomes. The chapters centre around three main areas, namely fundamentals for active and motivated learning, learning experiences for developing mathematical processes and use of ICT tools for learning through visualisations, simulations and representations. It must be noted that the 13 chapters do give a reader some ideas about meaningful learning experiences that promote mathematics learning. However, in no way are the 13 chapters a collection of all the know-how of the subject.

3 Fundamentals for Active and Motivated Learning

Learning results from students’ active participation in activities that provide learning experiences. In the classroom, teachers guide students in their learning through instructional activities. Often teacher’s knowledge and beliefs guide them in shaping the activities. So, for designing learning experiences that are relevant and engaging, some necessary fundamentals are explored in this book. Wong in chapter 2, notes that motivating students to learn mathematics with active engagement is a tough challenge for some teachers, especially so when the topics do not have obvious daily applications due to their abstract nature. He draws on theories and research in the literature related to motivation and derives a framework of motivation to learn called M_Crest. The framework covers six motivators: Meaningfulness, Confidence, Relevance, Enjoyment, Social relationships, and Targets. In the chapter mathematical examples are provided to illustrate the implementation of these motivators. Suggestions for teacher research to investigate the effects of the motivators are also discussed.

In chapter 3, Toh draws on the works of Taba (1962) and Tyler (1946) in the fields of curriculum design and development. He illustrates how each of Tyler’s five principles for selecting appropriate learning experiences may be drawn upon when designing learning experiences for effective instruction. He uses examples from secondary mathematics. Kwon, Park and Park, in chapter 4, note that learning by doing is an effective method of learning and authentic learning is a proponent of such a method. Drawing on Herrington and Herrington’s (2006) principles for designing authentic learning environments, they show how teachers may provide students with authentic learning experiences through 3 D printing technology.

Although research has shown that Pedagogical Content Knowledge (PCK) of teachers did predict student achievement, it was also found that teacher’s PCK is dependent on their Mathematics Content Knowledge (MCK) (Baumert et al., 2010). Beswick in chapter 5 uses items, measuring MCK and PCK, from an on-line survey to illustrate how these items may be used for professional learning and the kinds of knowledge teachers might need in order to use these sorts of items to create learning experiences that promote meaningful mathematics learning.

4 Learning Experiences for Developing Mathematical Processes

The seven chapters in this area provide teachers with ample examples of learning experiences that lead to the development of mathematical processes: thinking and reasoning skills. According to Fawcett (1938/1995) definitions and propositions socially constructed by students and their teacher facilitate “critical thinking”. In chapter 6, Shimizu illustrates how defining, extending and creating mathematical relationships offer students rich and meaningful learning experiences. He draws on a teaching experiment in Japan with grade 10 students on the topic of kite and “boomerang” and demonstrates how teachers may engage students in examining a definition, extending it and creating new ones. Cheng, in chapter 7, draws on the four teaching phases, developed by White and Mitchelmore (2010), and shows how mathematical abstraction may be facilitated in primary 5 classrooms. She also affirms that student-centred activities offer students with opportunities to be pro-active in their learning. They also enjoy working in groups, and communicating their ideas. The sequence of three activities, in the appendix to the chapter, provides teachers with an example of a learning experience for abstraction developing the concept percentage.

In the primary levels, learning what numbers mean, how they may be represented, relationships amongst them and computing with them are keys to developing number sense. McIntosh, Reys and Reys (1992) developed a framework comprising three broad categories and identified six related strands that provide a structure for designing learning experiences that facilitate the development of number sense. In chapter 8, Yeo illustrates how each of the strands may be developed in primary mathematics lessons through learning experiences which are outlined in the chapter. Hodgen, Küchemann and Brown, in chapter 9, note that when the teaching of algebra emphasises procedural manipulation of symbols over a more conceptual understanding learners see it as a system of arbitrary rules. Drawing on their experiences from the Increasing Competence and Confidence in Algebra and Multiplicative Structures (ICCAMS) study and they show how learning experiences may be planned to develop algebraic thinking amongst learners.

In chapter 10, Brown, Hodgen and Küchemann note that successful progress in learning mathematics depends on a sound foundation of the understanding of multiplicative structures and reasoning. This includes not only the properties and meanings of multiplication and division, but also their many links with ratio and percentage and with rational numbers - both fractions and decimals. As primary teaching can sometimes emphasise facility in calculation rather than the building of conceptual connections, these connections which take time to establish are neglected. This chapter draws on their experiences from the (ICCAMS) study and discusses how learning experiences can be planned to develop multiplicative reasoning using models to foster understanding. Mathematical induction (MI) is a technique that high school students may need when constructing proofs for mathematical assertions. In chapter 11, Tay and Toh, illustrate how the pedagogy of the technique of MI may be set within the natural environment of problem solving. They show how teachers may teach MI while engaging students in authentic problem solving. Zhao, in chapter 12, laments that the teaching of mathematical proofs lacks adequate emphasis in the A-Level curriculum for Singapore schools. He shows how appropriate scaffolding can be crafted ...