Economic Analyses Using The Overlapping Generations Model And General Equilibrium Growth Accounting For The Japanese Economy: Population, Agriculture And Economic Development

Population, Agriculture and Economic Development

- 356 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Economic Analyses Using The Overlapping Generations Model And General Equilibrium Growth Accounting For The Japanese Economy: Population, Agriculture And Economic Development

Population, Agriculture and Economic Development

About this book

This unique book contains novel and in-depth research regarding economic development in Japan. The authors examine economic development in Japan from both theoretical and empirical perspectives. Using general equilibrium growth accounting and the overlapping generations model, they analyze the relationships between population, agriculture and the economy. The research results are unprecedented and show the effects of increased adult longevity on national savings and the effects of demographic change on the industrial structure; the push-pull effects of technical change in agricultural and non-agricultural sectors and the positive effects of population on technical change and economic development.

Contents:

- Basic Considerations in the Analysis of Economic Development

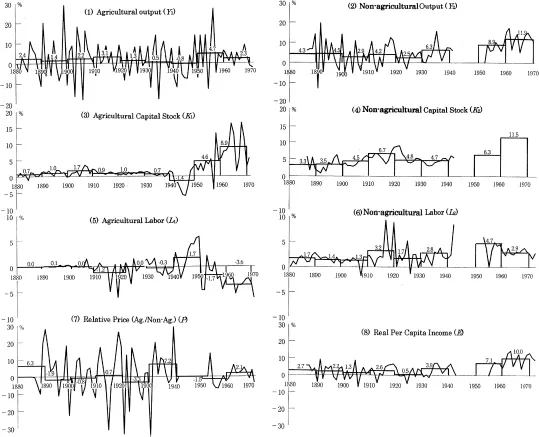

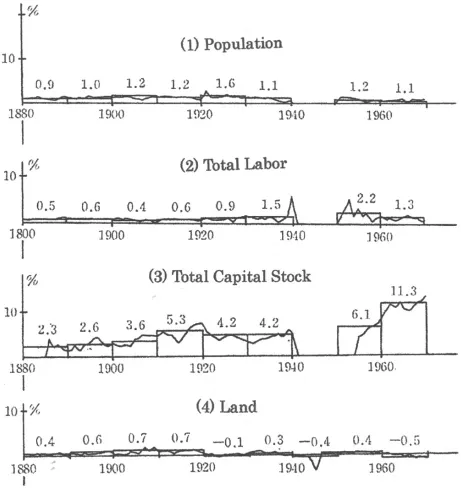

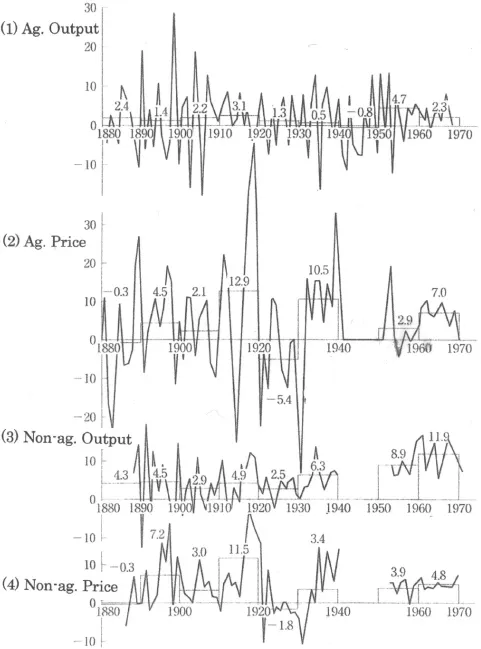

- General Equilibrium Growth Accounting for the Japanese Economy

- A Graphic Model of the Effects of Sectoral Technical Change

- Factor Mobility and Surplus Labor in the Japanese Economy

- Agricultural Surplus Labor and Growth Accounting for the Thai and Chinese Economies

- Interrelationship between Population and Economy

- A Consideration of the Positive Effects of Population

- The Effects of Adult Longevity on the National Saving Rate

- Two Demographic Dividends, Saving, and Economic Growth

- The Effect of Demographic Change on Industrial Structure

Readership: Students and researchers who are interested in Japan's economic development.

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Information

Chapter 1

Basic Considerations in the Analysis of Economic Development

Introduction

1. Theoretical Considerations of Agriculture, Population and Technical Change

1.1. Historical Growth Patterns in the Japanese Economy

1.2. Theoretical Consideration of Agriculture

1.2.1 Definition of “agriculture”

1.2.2 Characteristics of agriculture

| 1. | Definition of Agriculture: |

| Agriculture is defined as an order (or system) of human behavior with the objective of deriving an economically productive organic living. It is also objective behavior which is developed on the order of life extension. | |

| 2. | Characteristics of Agriculture: |

| (1) Main characteristics of demand for agricultural goods: (a) Small income elasticity (∵ stomach size is finite) → Engel’s law → The phenomenon of disproportional development between agriculture and non-agriculture. (b) Small price elasticity → Instability of agricultural prices and peculiar phenomena such as poverty during times of a good harvest. | |

| (2) Characteristics of supply and production for agricultural goods: (a) Agriculture uses considerable land area as an input, but the limitation of land results in the law of diminishing returns. (b) The production period and working process in agriculture are restricted to a specific natural period → In agriculture, it is impossible to rearrange all sequences of production time to a simultaneous production (because of the organic living) as opposed to the industrial sector → The amount of demand for labor and capital changes from season to season. These factors and the law of diminishing returns mean that large-scale production is unprofitable in agriculture. For example, most of the Japanese farmers work on a small scale. (c) An agricultural good has a long lifecycle and is, hence, vulnerable to the changes of climate. As stated above, agricultural prices fluctuate largely owing to low price elasticity. In addition, as most agricultural goods are perishable, it is not easy to maintain their freshness. Therefore, the price elasticity of agricultural supply is also small. Owing to these supply and demand characteristics, the growth rate, and partial productivity of land, labor productivity, capital productivity, and total productivity in agriculture are lower than in non-agricultural sectors. Therefore, agricultural labor declines relatively and absolutely depending on the time. We can also observe the disproportional development between agriculture and industry. | |

| 3. | Contribution of Agriculture to the Economy: |

| (a) Agriculture supplies food and raw materials. (b) Agriculture supplies the source of capital stock through land tax and other taxes which are absorbed from the agricultural sector. (c) Agriculture supplies labor to the non-agricultural sector. (d) Agriculture obtains foreign currencies. (e) Agriculture provides a domestic market for non-agricultural products. Recently, the following three contributions were evaluated in Japan. First is the contribution of agriculture to public wealth, given a large external economy connected with agriculture. Second is the contribution of agriculture in maintaining social balance. Agriculture is a basic industry in the rural areas of Japan → Agriculture keeps people in rural areas and maintains a social balance between urban and rural areas. Third, is the contribution to the ethos of a community, society, and nation. Festivals, temples, and shrines have their origin in agriculture. These three contributions are especially important in the present world, judging from the prevalent environmental problem. |

| 1. | Definition of Population: |

| Population is defined as the total number of people who live in a certain place. | |

| 2. | Characteristics of Population: |

| (a) Other than quantitative characteristics, population also has quality dimensions such as age, occupation, and gender. (b) Population shows a social, organic, and reproductive movement, and birth and death rates change the size and structure of population. (c) Population has a very gradual and long-term movement. For example, the gestation period for human beings is nine months, and the minimum age to enter the labor force is 15 years or more. (d) Population is closely related to the economy. | |

| 3. | Contribution of Population to Production: |

| (1) Negative contribution of Population to the Economy: (a) Population could decrease per capita income (by definition), other things being equal. (b) Population could change the age structure and decrease the ratio of economically active members in the total population. Therefore, per capita income decreases. (c) Children increase the marginal utility of money and increase consumption. Therefore, household savings would decrease. (d) Per capita public service would decrease. | |

| (2) Positive Contribution of Population to the Economy: (a) As labor is drawn from the population, it contributes to production. Moreover, several studies reveal that parents have a tendency to work harder when they have children. In addition, labor contributed by children is important in an agricultural society. (b) The benefits of economies of scale and division of labor appear when there is a large population. | |

| (c) Necessity is the mother of invention. (d) With a large population, diversity in knowledge and skill sets allow for the development of novel techniques in using resources. In case of a large population, the number of geniuses is also larger and contributes more to the economy. | |

| (3) Contribution of Population to Consumption, Culture, Education, and Miscellaneous Fields: (a) Youths are more flexible and adapt to new occupations with more ease. This results in optimal allocation of labor. In addition, as they produce more than they consume, they save more. (b) Population growth and higher population density makes a positive contribution to the creation of infrastructure, such as roads, transportation, sanitation, and education. Overhead cost becomes relatively cheaper for a large population. A higher population growth rate leads to higher irrigation rates and higher investments in agricultural infrastructure as well. |

1.2.3 Contribution of agriculture to the economy

...Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Preface

- About the Authors

- Chapter 1. Basic Considerations in the Analysis of Economic Development

- Chapter 2. General Equilibrium Growth Accounting for the Japanese Economy

- Chapter 3. A Graphic Model of the Effects of Sectoral Technical Change

- Chapter 4. Factor Mobility and Surplus Labor in the Japanese Economy

- Chapter 5. Agricultural Surplus Labor and Growth Accounting for the Thai and Chinese Economies

- Chapter 6. Interrelationship between Population and Economy

- Chapter 7. A Consideration of the Positive Effects of Population

- Chapter 8. The Effects of Adult Longevity on the National Saving Rate

- Chapter 9. Two Demographic Dividends, Saving, and Economic Growth

- Chapter 10. The Effect of Demographic Change on Industrial Structure

- Appendix

- References

- Index