![]()

CHAPTER 1

Biodiversity of Medicinal Plants

Kirsten Yacoub, Katharina Cibis and Corinna Risch

ABSTRACT

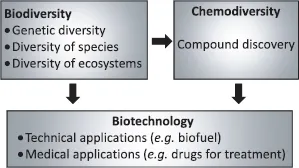

Biodiversity describes the universality of all life forms, i.e. plants, animals and microorganisms, and the variety of ecosystems they live in. There are three classes of biodiversity, namely genetic diversity, species diversity and ecosystem diversity. Biodiversity is associated with chemodiversity, which plays a significant role in the discovery and development of drugs and medical pharmacotherapies. In addition to medical applications, biodiversity of microorganisms plays a crucial role in biotechnology and industrial biocatalytic processes. It is expected that in the future, biotechnology will produce high-quality bioproducts, which could replace fossil fuels. In this context, it is important to note that biodiversity is being threatened by the human species. Biodiversity is being destroyed by global environmental changes, such as changes in the atmospheric composition land degradation, depletion of fisheries and shortage of freshwater. Reduced biodiversity may lead to fewer natural chemical substances and hence reduced potential for medical and biotechnological applications.

1.INTRODUCTION

The term“biodiversity”describes the universality of all life forms, i.e. plants, animals and microorganisms, and the variety of ecosystems they live in. It also encompasses the differences in the genetic make-up and the numerous ecological processes therein.1 Biodiversity is divided into three classes (Fig. 1). The first class is referred to as genetic diversity, and describes the variability of the genetic make-up between and within species. The second class is the diversity of species and the third class is the diversity of ecosystems.1 Biodiversity contributes greatly to the chemodiversity of pharmaceutical substances, many of which originate in nature and are significant for human health.1 Modifications and changes in biodiversity can have an extensive impact on humans and their environment.2

Figure 1 From Bio-and chemodiversity to biotechnology.

2.CLASSIFICATION OF BIODIVERSITY

There is a widely held belief that biodiversity refers to the enormous number of plant and animal species. However, biodiversity in fact is much more than that. It corresponds to the complex natural living system, its structure and diverse levels of organization.1 The three classes of biodiversity mentioned earlier i.e. genetic diversity, species diversity and ecosystem diversity are described in detail in the following sections.

2.1.Genetic Diversity

The genetic code is universal; it applies to all species. Genetic diversity does not only refer to individual variation in genomes within a species, but also to genetic variation between different species.1 To date, scientists have identified about 1.7 million species on our planet.3 The genomes of various species, including both eukaryotic and prokaryotic organisms, have been sequenced. There are currently fully-sequenced genomes of 2927 different species. One hundred and forty-six of them are archeal, 2615 are bacterial and 166 are eukaryotic genomes.4 Among these sequenced genomes are those of the archea Methanococcus maripaludis X1,5 the bacteria Escherichia coli6 and the eukaryote Homo sapiens.7

Based on the presence of homologous genes in different organisms, it is possible to estimate how closely related two species are from a phylogenetic point of view. In this way scientists have been able to prove that humans, yeasts and sunflowers are closely related. The use of genetic data has revolutionized the evaluation of phylogenetic relationships, as using phenotypic details sometimes leads to inaccurate assumptions of evolutionary relationships.8 Archaeal and eubacterial genomes can be sequenced much faster than eukaryotes, because of their smaller size.8 Information about complete genomes, chromosomes or large segments of DNA is collected in databases (e.g. Ensembl, NCBI (National Center for Biotechnology Information), GOLD (Genomes OnLine Database)).4

The benefits of DNA sequencing are numerous. Taxonomists do not have to identify species by morphological features any more, which are not always indicative of relationships between species. Using cutoffs in genetic variation provides a more subjective way to define a species.

2.2.Species Diversity

The second kind of biodiversity is species diversity.1 At least half a billion species have existed on earth. Currently, there are probably about 20–80 million species, with many of them listed as endangered.9 About 1.4 million species have been morphologically described,8 265,000 of which are flowering plants.1 The extinction rate at present is estimated to be about three species per hour.9 Natural selection has resulted in a huge genetic variation favoring the generation of new species.9 The actual number of species in a given geographic region depends on speciation, extinction, and immigration and emigration rates of the species in the area.10

2.3.Ecosystem Diversity

The third kind of biodiversity is ecosystem diversity, which refers to the variety of habitats that exist. Ecosystem diversity refers not only to abiotic conditions such as climate, soil, etc., but also to the communities of organisms and ecological processes, which play a major role in defining an ecosystem.1

The fact that many species are still unknown and have not been morphologically or genetically described necessitates further systematics and taxonomy. Biodiversity research is important not only for the discovery and classification of new species, but also for the preservation of species.9

3.BENEFITS OF BIODIVERSITY

Humanity benefits greatly from biodiversity in many ways. Three of the most important advantages derived from the earth’s vast biodiversity are the use of chemical substances from nature, innovations in biotechnology and the impact of biodiversity on nutrition and health. Each of these three advantages is explained in the following sections.

3.1.Chemical Substances from Nature

The natural compounds produced by many plants play a significant role in drug discovery and development. Roughly half (49 percent) of the new small-molecule chemical entities introduced between 1981 and 2002 were chemical substances of natural origin, semi-synthetic or synthetic substances based on natural products.11

3.1.1.Definition

Natural products include extracts, mixtures of many compounds, and their isolated chemical constituents that are naturally biosynthesized.12 Valuable natural products can come from terrestrial or marine life forms, e.g. plants, fungi, bacteria, protozoans, insects, other animals or humans.12 Natural products can be subdivided into primary and secondary metabolites. Primary metabolites are indispensable for nutrition of the organism that produces them, and are universal in nature. On the contrary, secondary metabolites have beneficial features such as protection against parasites or predators or attracting pollinators, but are not essential to growth and reproduction of the producer. In general, secondary metabolites display larger chemical diversity.12

3.1.2.Advantages and disadvantages of natural products over synthetic substances

Chemical substances of natural origin differ from synthetic ones in that they display much greater structural diversity. Natural products typically have an increased steric complexity and a higher number of chiral centers than synthesized chemicals. They frequently bear a higher number of oxygen atoms and solvated hydrogen-bond donors and acceptors. Natural products have greater molecular rigidity, a broader distribution of molecular mass, a higher octanol-water partition coefficient, and a greater diversity of ring systems.11

The great chemical diversity of natural products is a result of evolutionary pressure, which acts on every organism. The biosynthesis machinery of an organism is subject to continuous mutation, which allows it to adapt to changing environments. In the course of evolution, an enormous variety of chemical substances has developed.12 The architectural complexity of natural products compared to synthetic substances makes subsequent modifications of natural molecules difficult and expensive.11 Furthermore, this complexity results in difficulties in the procedures for total chemical synthesis. As a result, many commercially available natural products are biosynthesized in the living organism or, if possible, in cell cultures. For example, isolation from Papaver species is still the most economical way of obtaining alkaloids such as morphine or codeine.12 Another benefit of natural products is their increased compatibility and stability in biological milieus.11

In summary, chemical substances of natural origin are preferable molecules for the development of new drugs.11 The plant kingdom still holds huge potential because only 10 percent of higher plants worldwide have been analyzed for chemical ingredients and biological activity. Furthermore, only half of the about 100,000 secondary metabolites that were discovered to have biological activity have already been investigated.11

3.1.3.Examples of drugs from nature

Alkaloids such as morphine, narcotine, emetine, strychnine, chinine, cinchonine, caffeine, atropine, etc., represent a highly potent class of drugs derived from nature.12 The antimalarial drugs quinolin and related aryl alcohols are based on quinine, an ingredient of Cinchona bark.11 Artemisin, an ingredient of the herb Artemisia annua, is effective against fever. Several semi-synthetic derivates of artemisin are used as antimalarials.11 Macro-cyclic spermine alkaloids isolated from the stem bark and leaves of Albizia adinocephola interact with the antimalarial target plasmepsin II.11

Vinblastin and vincristin from Catharanthus roseus are important anticancer drugs....