![]()

Part I

Beyond the Standard Trade Model

![]()

Chapter 1

Free Trade and Its Alternatives*

Sven W. Arndt

Abstract

Free trade as the widely preferred policy regime has enjoyed a very long and largely successful run. In recent years, however, political support for it has cooled substantially, especially in the arena of multilateral trade negotiations. Its wide acceptance was in part nurtured by memories of the devastating protectionism of the interwar years. Interestingly, the strongest and most unequivocal intellectual support for it comes from a model whose assumptions are more than a little at odds with modern reality. The case for free trade becomes more ambiguous under circumstances involving product differentiation and intra-industry trade, economies of scale, imperfect competition, and externalities.

Nevertheless, while introduction of greater realism weakens the universality of the case for free trade; it does not add up to an argument for protectionism. When markets are free, it can readily be shown that trade should also be free. In the years since World War II, trade barriers have been reduced significantly, while many markets have become less free, with greater concentration of economic power and rising volumes of transactions that do not take place in markets at all. This is particularly true in the financial services industries. Hence, the alternatives to free trade are not just simply a return to protection, but strengthening competition in markets that are encumbered by public and private distortions.

JEL Classification: F11, F12, F15

Keywords: Free trade; Protection; Market distortions

1. Introduction

The era of free or freer trade is now well over half a century old. Trade in goods, as well as services is significantly less encumbered than at the end of World War II and most of the world’s economies are more open and more fully integrated into the global system than ever before. World trade has grown more rapidly than world production and many traded goods and services have become internationalized as cross-border production networks have multiplied. Even non-tradables are feeling the winds of foreign competition, as some of their parts and constituent activities and tasks have become tradable.

The belief that free trade is superior to its alternatives has enjoyed wide and robust support in many parts of the world and has served as the guiding principle for the series of multilateral trade negotiations that began shortly after the war, but are currently stalled in the Doha Round. Yet much of the theoretical case for free trade is based on a model which assumes an economic world in which markets are perfectly competitive and free of distortions and populated by firms that are small and not too-big-to-fail. There are no externalities or scale economies in this world; all goods and services are tradable, trade is always balanced and economic growth just happens.

This view of the world is more than a little at odds with reality. While reduction of trade barriers and opening of national economies have brought fresh winds of competition, market structures in many parts of the world have evolved in the opposite direction, with fewer firms and more concentration of economic power, with capture of economic policy by private interests in a variety of instances, and with non-trivial information asymmetries and assorted externalities. There may be grounds for arguing that freeing markets from the trade restrictions that remain may be less urgent than freeing markets from the welter of other distortions and barriers to efficient utilization of the world’s productive resources.

This chapter begins by reviewing the basic case for free trade in terms of the workhorse factor-proportions model. The conclusions of this “benchmark” model are then stress-tested by removing each of the key assumptions in turn. Not surprisingly, the case for free trade becomes less airtight, as a variety of specific market situations arises in which trade-based barriers such as tariffs or non-trade interventions such as production and other subsidies can produce superior welfare outcomes. But these theoretical findings of superiority do not necessarily translate into interventionist policy prescriptions, because in many cases the costs associated with practical implementation may exceed the expected benefits.

2. The Benchmark Model

The benchmark model assumes perfect competition in all markets, constant returns to scale and no externalities or market distortions of any kind. It focuses on “comparative advantage” based on differences across countries in resource endowments and across industries in factor intensities. Countries are assumed to be differentially endowed with the main factors of production—land, labor (skilled and unskilled) and capital—and technologies are assumed to differ across products ensuring that the factors will be combined in different proportions at given relative factor prices.

The essential conclusion of this model is that the economic welfare of each country is best served when it focuses on producing goods and services that make intensive use of the factor or factors of production with which it is relatively well-endowed. Each will then produce more than it consumes of goods and services in which it has comparative advantage, while producing less than it consumes of goods in which it has comparative disadvantage. Each exports its excess production of the former, while importing the latter in order to bridge the shortfall of domestic production relative to consumption. It is within these conditions that the welfare results of free and restricted trade are compared.

The small country in partial equilibrium

There are two widely used approaches to the analysis of economic welfare in this context. One, the so-called partial-equilibrium approach, focuses on the market for a single good or service, while the other — the general-equilibrium approach — considers economy-wide effects. In both cases, the welfare results depend on whether a country is small or large vis-à-vis the rest of the world, where smallness means that the country has no influence on the world price of any product.

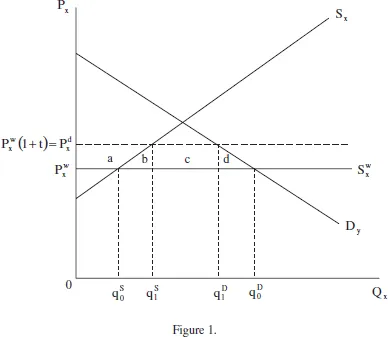

On the import side, the partial-equilibrium version of the small-country case is depicted in

Figure 1. The smallness assumption ensures that the country faces a horizontal world supply curve,

, and given world price

. At that price, domestic production is at

, domestic consumption is at

, and imports of

cover the gap between domestic demand and supply. Imposition of an import tariff works like a tax by raising the tariff-inclusive price to

, which is equal to

+ t if the tariff is a “specific” tariff or

(1 +

t) if the tariff is an ad valorem tariff. At this price, domestic production expands to

, while consumption shrinks to

. Imports fall to

.

The concepts of consumer and producer surplus are used in this context to assess the welfare effects of the tariff. Consumer surplus shrinks by area a + b + c + d; producer surplus expands by area a and government collects tariff revenue equal to area c. It is clear that the bulk of the tariff’s effect is to redistribute income or economic wellbeing from consumers (who are the losers in this case) to producers and the beneficiaries of government expenditures funded by tariff revenue.

In order to assess the overall welfare effect, the benchmark model makes an assumption that may not always be true in the real world: it assumes that winners and losers attach equal value or utility to the transferred amounts. Hence, the loss of area a is worth as much to consumers as its gain is to producers. The same calculation is applied to area c, which transfers income from consumers to government. Under this assumption, the winners’ gains “cancel” the losers’ losses, implying that this income redistribution has no net effect on “national” welfare.

That leaves the effects captured by triangles b and d, known as the efficiency or “deadweight” losses. The first is the result of “trade diversion” from lower-cost world producers to higher-cost domestic firms and the second represents the loss of consumption brought about by the price increase. The net effect of the tariff is thus a welfare loss to the nation equal to area b + d. In the absence of the assumption of equal marginal utilities, the net result will be more or less negative, depending on whether consumers attach greater or lesser value to the transfer than the recipients.

The tariff creates welfare losses for the economy because it reduces the efficiency of resource utilization. It is an inefficient means of supporting home production, because it burdens consumers with higher prices. Any alternative policy that can achieve the same increase in domestic output without raising the price paid by consumers will be superior. As we shall see later, a per-unit production subsidy, equal to

, the gap between the world price and the tariff-inclusive domestic price, achieves the same increase in production at lower welfare cost. The subsidy is a more efficient method of achieving the domestic policy objective, but it is also more transparent than the tariff and hence is politically less appealing.

Just because winners and losers value the transfer equally does not imply that the potential losers should not oppose the policy. Consider the following bargaining scenario. Could the losers compensate the winners in order to make them indifferent between the two trade regimes and still come away “better off” with free trade than with the tariff? Could the winners, on their part, compensate or “bribe” the losers to accept the tariff and still be better off with the tariff than with free trade?

In order to make producers and government outlay recipients indifferent between the two trade regimes, consumers would have to offer them compensation in the amount of areas a and c, respectively. Maintaining free trade would thus cost consumers area a + c, while the tariff regime costs consumers a + b + c + d. On the other side, producers and the government would have to pay consumers a + b + c + d in order to make them indifferent between the two trade regimes. Clearly, this would be an inferior solution by the amount b + d. This “double-bribe criterion” is another way of showing the superiority of free trade.

The large country in partial equilibrium

The large country is able to influence world prices by changes in its behavior. It is a price “maker” rather than a price “taker” in ...