- 268 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Dark Energy

About this book

This book introduces the current state of research on dark energy. It consists of three parts. The first part is for preliminary knowledge, including general relativity, modern cosmology, etc. The second part reviews major theoretical ideas and models of dark energy. The third part reviews some observational and numerical works. The aim of this book is to provide a sufficient level of understanding of dark energy problems, so that the reader can both get familiar with this area quickly and also be prepared to tackle the scientific literature on this subject. It will be useful for graduate students and researchers who are interested in dark energy.

Contents:

- Preliminaries in a Nutshell:

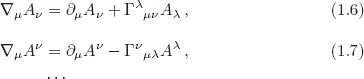

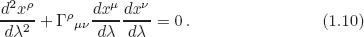

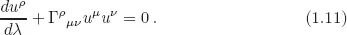

- Gravitation

- Matter Components

- Cosmology

- Theoretical Aspects:

- Introduction to Dark Energy

- Weinberg's Classification

- Symmetry

- Anthropic Principle

- Tuning Mechanisms

- Modified Gravity

- Quantum Cosmology

- Holographic Principle

- Back-Reaction

- Phenomenological Models

- The Theoretical Challenge Revisited

- Observational Aspects:

- Basis of Statistics

- Cosmic Probes of Dark Energy

- Dark Energy Projects

- Observational Constraints on Specific Theoretical Models

- Dark Energy Reconstructions from Observational Data

Readership: Graduate students and researchers interested in Astrophysics and Cosmology.

Key Features:

- This book presents comprehensive overview of theoretical and observational aspects of research on dark energy.

- Almost all of major works on this area are introduced.

- Students and Researchers can use this like a handbook

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Part I

Preliminaries in a Nutshell

1

Gravitation

1.1The Curved Spacetime

1.2The Curved Spacetime: An Example

Table of contents

- Cover page

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Foreword

- Preface

- Contents

- Part I Preliminaries in a Nutshell

- Part II Theoretical Aspects

- Part III Observational Aspects

- Index

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app