![]()

PART I

Diplomacy for Science:

Facilitating International Science

Co-operation

![]()

CHAPTER 2

US Science Diplomacy with Arab Countries

Cathleen A. Campbell

In Cairo, Egypt in June 2009, US President Barack Obama delivered a pivotal speech in which he outlined a ‘new beginning’ in US engagement with the Muslim world. He announced a wide range of initiatives that included a commitment to expand science and technology engagement. President Obama specifically called for the creation of centres of excellence and for increased cooperation in health. He urged partnerships and investment to assist entrepreneurs to create new businesses and jobs. He also announced the appointment of US ‘science envoys’ to collaborate with Muslim countries on programs related to energy, agriculture, information technology and water (Obama, 2009).

At first glance, President Obama’s call to action appears similar to previous US presidents’ calls for increased international cooperation in science and technology. Presidents and prime ministers often urge cooperation in science during overseas speeches. International summits and ministerial meetings often result in new agreements in science and technology. In this particular instance, however, the push for more science and technology engagement with Muslim countries was indeed tied to the desire to improve relations with those countries. A report issued in February 2009 by WorldPublicOpinion.org, based on the results of in-depth surveys in three countries supplemented by worldwide polling, showed strong negative views of the US government within Muslim countries. The study found that then ‘…the US is widely seen as hypocritically failing to abide by international law, not living up to the role it should play in world affairs, disrespectful of the Muslim people, and using its power in a coercive and unfair fashion’ (Kull et al., 2009). Polling done by the Pew Centre consistently showed strong admiration for US science and technology, even in countries where the overall views of the United States are low. For example, in a 2007 survey, 83 percent of Malaysians, 68 percent of Jordanians, and 67 percent of Palestinians expressed a positive view of US science and technology (Kohut and Richard, 2009). Expansion of cooperation in an area where there is respect for US progress and a desire to learn from the US experience provided an opportunity — at least in principle — to help improve the perception of the US in Muslim majority countries. Scientists and policy leaders in the region also recognize this potential. In October 2011, the Islamic World Academy of Sciences (IAS) convened its 18th international conference in Doha, Qatar under the theme: The Islamic World and the West: Rebuilding bridges through science and technology. One of the three conference objectives focused on hearing from the over 200 participants about ‘…ways to bridge the divide between the Islamic World and West, particularly through science and scientific and technological collaborations’ (IASWorld, 2012: 3).

President Obama’s June 2009 speech raised expectations about the potential of science engagement to improve relations. As in many complex situations, the reality is much harder to achieve. The difficulty of turning President Obama’s grand vision into actual programs, the challenge of mobilizing resources in times of financial constraints, and the complexities inherent in trying to implement programs in countries experiencing ongoing political and economic turmoil, have resulted in slower implementation than many anticipated.

In his Cairo speech, and in follow-up actions, the Obama Administration has focused on improving relations with Muslims worldwide, including those living in Asia, the Middle East, Africa and Europe. The Muslim world encompasses more than fifty countries that vary greatly in population, economic output, natural resources, education and scientific output. This chapter will focus on a subset of countries that due to longstanding political and economic relationships, as well as the legacy of 9/11, have special significance to the United States. This chapter will address US science diplomacy with 20 Arab countries1 in the Middle East, Africa and the Gulf region. Other Muslim-majority countries, such as Indonesia, Pakistan, Iran, and Malaysia will not be discussed in depth. However, they may be referenced for comparison or be included in selected data sets.

Defining Science Diplomacy

Recognition of science diplomacy as an important component of international relations is growing. Policymakers around the world are referencing science diplomacy in speeches; experts are convening conference panels or workshops on the topic. Press interest is growing; and there is a new journal devoted to the topic — Science and Diplomacy, published by the Centre for Science Diplomacy of the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS). This recent surge in writing and analysis is welcome, particularly if it helps to shape a common understanding of science diplomacy, enable those involved in science diplomacy to document and share lessons learned from their experiences, and lay groundwork for establishing a common framework for assessing science diplomacy’s impact.

While progress is being made in documenting and sharing lessons learned, less progress is being made in reaching a common definition of science diplomacy and developing a common framework for assessing its impact. To some, science diplomacy refers to any type of international science cooperation, including well-established government-to-government cooperation between allies or any multilateral science cooperation such as that taking place at the Large Hadron Collider in Europe where nearly 8,000 scientists and engineers representing 60 countries are working. Indeed, the Large Hadron Collider project — particularly the intergovernmental involvement in negotiating the large-scale collaboration, can be viewed as an example of ‘Diplomacy for Science’, which AAAS and the UK Royal Society define as the process of facilitating international science cooperation through diplomacy’. Two other dimensions of science diplomacy, as defined by AAAS and the Royal Society, include ‘Science in Diplomacy’, which is ‘informing foreign policy with science advice’, and ‘Science for Diplomacy’, which is ‘the process of using science cooperation to improve international relations’ (The Royal Society, 2010).

Others have adopted this broad-brush approach to science diplomacy. In an August 2013 speech, the Science and Technology Advisor to the US Secretary of State defined science diplomacy as: ‘(1) science and technology aiding diplomacy (for the many diplomatic issues where scientific and technological information is critically important and even for those cases where science and technology engagement can open doors for dialogue on other issues); (2) diplomacy advancing science and technology (such as by negotiating multinational arrangements for building large facilities and gaining access for research in unique locations) and (3) science and technology helping to solve national, regional and global problems (such as by creating new options and paths for making progress on the “wicked problems” too difficult for politicians to resolve alone)’ (Colglazier, 2013).

The AAAS Centre for Science Diplomacy, established in 2008, takes a more nuanced approach. Its website clearly highlights the relationship-building benefits of science diplomacy. Further, it notes the Centre’s interest in science diplomacy serving ‘…as a catalyst between societies where official relationship might be limited and to strengthen civil society interactions through partnerships in science and technology’ (AAAS, 2014). It is this potential to improve relations through science engagement that gives special meaning to science diplomacy and sets it apart from more traditional international science and technology cooperation.

However, this approach to science diplomacy makes it difficult to monitor and evaluate its outcomes and impacts. An important value of science diplomacy is building trust and confidence between countries, particularly those in conflict or with strained relations. But trust is difficult to measure and the impact that those trusted relations have on improving relations between countries more broadly is even harder to measure. Advocates of science diplomacy often cite the dialogue between US and Soviet scientists during the Cold War as an example of science diplomacy. Scientists and engineers involved in that dialogue — both American and Russian — believe that the relationships and understanding developed during those years enabled the two communities to successfully collaborate on key science and security challenges after the collapse of the Soviet Union. Equally important was the fact that some of these scientists (particularly in Russia and other Eurasian countries) had reached high-level government positions and the experience they had working with US counterparts paved the way for compromise and collaboration on key issues. But this process and these relationships evolved over many years, suggesting that any potential impacts of science diplomacy efforts with Arab countries will take years, if not decades, to realize.

Potential for Science Diplomacy with Arab Countries

Although the US has cooperated with many Arab countries for years, there is considerable room to expand existing collaboration and to use science diplomacy to engage countries with which connections are weak and to work collaboratively to solve common challenges. Arab countries share strong cultural and linguistic links but vary greatly economically, politically, socially and, of course, scientifically. While there are some exceptions, Arab countries generally lag behind other countries in terms of science infrastructure, investment, output, and collaboration with other countries. Working in partnership with these countries to help build indigenous science and engineering capacity and increase global integration represents a significant science diplomacy opportunity.

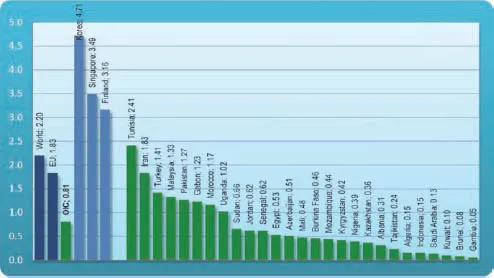

Arab countries comprise a very small share of global expenditures on research and development (R&D). At the individual country level, R&D intensity (the gross domestic expenditure on R&D as a percentage of GDP) generally falls far below the world average (2.2 percent). Figure 1 shows that only Tunisia exceeds the world average and only Tunisia and Morocco have met the 1 percent target established by the Organization of Islamic Cooperation (OIC) for its members (all of the 20 Arab countries featured in this chapter are members of the OIC).

Figure 1. R&D Intensity (in percentage).

Note: Data for the most recent year available between 1999 and 2010. Image taken from OIC (2011: 4–6).

Similarly, R&D expenditures per capita lag other regions. Among Arab nations, Tunisia ranks highest, at US$100.5million. The second highest Arab country — Kuwait — spends considerably less per capita (US$31.5million). All other Arab countries fall below the OIC average of US$27.7milliom, and far below the world average of US$219million and the EU average of US$601million (OIC, 2011: 6).

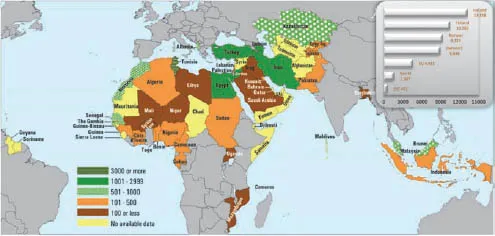

The number of scientific researchers as a percentage of the total population is also quite low. For all OIC countries the average number is 451 scientists per million people, which compares poorly against the global average of 1,507 per million inhabitants. Figure 2 shows significant disparity among Arab countries. According to the UNESCO Science Report 2010, which used survey data to estimate the number of researchers based on full-time equivalents, Jordan and Tunisia have the highest number of researchers among the Arab countries (Badran and Zou’bi, 2010: 261).

One of the key indicators used to assess research productivity is the number of scientific articles published in indexed journals. Scientific publications per million of the population in the Arab world reached 13,754 in 2008, led by Kuwait, Tunisia, Jordan, Qatar and UAE. This almost doubles the number of publications (7,446) in 2000, but is well below that of global leaders, including the US (323,000), China (137,000) and Germany (85,000) (Organisation of Islamic Cooperation (OIC, 2011: 12).

Figure 2. Researchers per million people.

Note : Headcount data for the most recent year available. Image taken from (OIC, 2011: 2).

Science is increasingly a global enterprise and global integration is a necessary component of strong national science systems. Success in publishing research results in international, peer-reviewed journals is one indication of global integration. According to the US National Science Foundation, the share of the world’s science and engineering articles with international co-authors grew from eight percent in 1988 to 23 percent in 2009. For some countries or regions, the percentages were much higher. For example, the share for the US grew from about 11 percent in 1989 to 31 percent in 2009; EU grew from about 18 percent to 42 percent in 2009; and China grew from about 23 percent in 1989 to 26 percent (National Science Board, 2012).

The UNESCO Science Report of 2010 shows an increase in co-publications involving scientists from the region. Citing data from Thomson Reuters Inc., the report notes that between 2000 and 2008 there was a steady increase in the number of Arab scientists collaborating with the diaspora. For example, approximately one third of the 3,963 articles published by Egyptian scientists in 2008 were co-authored by scientists outside Egypt. Similar trends were seen in Tunisia, Saudi Arabia, Algeria, UAE, Jordan and Lebanon (UNESCO, 2010: 264–267).

The above data demonstrate that, despite some progress in the last decade, Arab countries lag significantly in their production and use of indigenous science and technology knowledge. Across the board, Arab countries that are interested in creating a knowledge-based economy need to invest more in education, research and entrepreneurship, and in creating the necessary infrastructure and policy frameworks to support science, technology and innovation. These are areas where the United States, with its unique experience in fostering science and technology based economic growth, can utilize science diplomacy to improve relations with the Arab world. However, US science diplomacy efforts must be carefully aligned with the interests, capabilities, and absorptive capacity of the partner country. The increased attention that many Arab...