![]()

Chapter 1

What is a Laser?

Lucile Julien

Professor, Université Pierre et Marie Curie,

Laboratoire Kastler Brossel, Paris, France

Catherine Schwob

Professor, Université Pierre et Marie Curie,

Institut des NanoSciences de Paris, Paris, France

The first laser was built more than 50 years ago, in May 1960: it was a pulsed ruby laser. It was a simple laboratory curiosity and nobody knew what its usefulness could be. Other devices were rapidly demonstrated, and the variety and number of lasers in the world increased at a huge rate. Currently, the annual laser world market is worth about 6 billion dollars. Thanks to the remarkable properties of laser light, laser applications increase steadily in the domains of industry, building, medicine, telecommunications, etc. One can find many lasers in research laboratories, and they are used more and more in our everyday life and almost everybody has already seen a laser beam. The goal of the first chapter of this book is to explain simply what a laser is, how it is built and how it operates. Firstly, let us point out the outstanding properties of the laser light.

1.1. A Device Which Provides a Quite Distinctive Beam

1.1.1. The laser beam

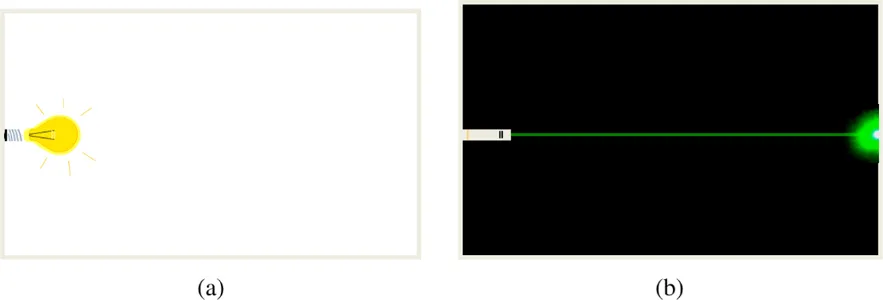

A laser beam can be recognized at first glance since it differs from ordinary light. Physicists say that it is a beam of coherent light. We will see here that its properties are different from those of light emitted by ordinary lamps, that we will call “classical lamps” in the following. Such lamps are of different types: incandescent light bulbs, tube lights, and light-emitting diodes. But they all emit light in all directions, which is convenient to light up a room or a given space, as shown in Figure 1.1. On the contrary, a laser emits a narrow beam giving a localized light spot when something like a wall gets in its way.

Figure 1.1: The light emitted by a classical lamp (a) enlightens in all directions; the laser (b) emits a narrow beam in a given direction.

Even if the laser beam propagates over large distances, it remains parallel and well-defined. This property is called spatial coherence. Another property of a laser beam, in the visible domain, is its color, which is often pure, that means not superimposed to other colors. This second property is called monochromaticity or temporal coherence.

We can then give a first answer to the question “What is a laser?”: A laser is a device which delivers coherent light (both spatially and temporally). Let us see now how this light is generated; we begin by recalling the physical nature of light.

1.1.2. What is the nature of light?

Light is an electromagnetic wave, which means electric and magnetic fields coupled together and propagating in space, the combination of both being called an electromagnetic field. Since the 19th century, it has been known that a varying electric field induces a magnetic field and, in the same manner, a varying magnetic field induces an electric field. The coupling of these two fields with each other, and with electric charges and currents, are described by Maxwell’s equations (1831–1879) which give the behavior of an electromagnetic field and the way it propagates. In an electromagnetic wave, both fields oscillate at the same frequency, that is, their number of oscillations per second, and propagate together in vacuum at the velocity c, known as the velocity of light.

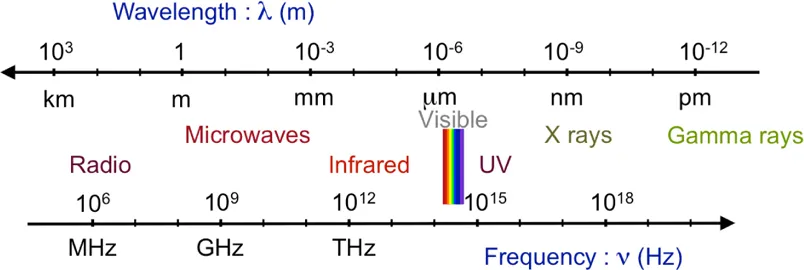

Figure 1.2: The various domains covered by electromagnetic waves.

The velocity of light is a universal constant. From the theory of relativity, developed by Einstein in 1905, we know that this velocity is the same for all observers. Due to the new definition of the meter in 1983, it has now a fixed value in the international system of units, given by 299,972,458m/s, which is about 300,000km/s.

Light is an electromagnetic wave, but the domain of electromagnetic waves is much wider than visible light. It spreads over a large frequency domain, shown in Figure 1.2, from radiofrequency waves in the low frequency range to gamma rays in the high frequency one. The optical domain lies in the middle of this spectrum, with the visible range surrounded by infrared on the one side and ultraviolet on the other.

Each frequency is related to a wavelength, given by

Large wavelengths are then associated with low frequencies and small ones to high frequencies. In the visible domain, the wavelengths range from 400 to 800nm (1nm = 10

−9 m that is 1 billionth of meter). In this domain, our eye associates a color to a group of wavelengths: violet, blue, green, yellow, orange, red, in order of increasing wavelengths. These rainbow colors are those obtained when white light is dispersed by a prism or a drop of water.

At the center of the visible spectrum, the wavelength is 600nm and the frequency 500THz, that is 500,000 billion oscillations per second (1THz = 1012 Hz). Frequency is the inverse of time (1 Hz = 1 s−1); that is why monochromaticity mentioned above is called a temporal property of light.

1.1.3. Photons different from others

During the 20th century, quantum mechanics has deeply changed the way we describe the physical world, challenging many ideas inherited from classical physics.

As an example, it taught us that each particle can also behave like a wave. Usually the wave associated to an atom has a too short wavelength to be detected. However, when atoms are cooled down to very low temperature, their wave behavior begins to show up since their wavelength is much larger as their velocity is lower: Chapter 6 contains detailed methods used to cool down atoms with lasers, and exploiting the quantum properties of cold atoms. Quantum mechanics is needed to fully understand the electromagnetic field. Understanding some of its properties involves a description in terms of particle flux; this is the field of quantum optics (see Chapter 6). The particles of light are called photons. Unlike atoms, they are massless and they propagate in vacuum with the velocity c.

How can we link photons to electromagnetic waves? A wave is characterized by its frequency, its direction of propagation and its polarization (related to the direction of the electromagnetic field). These parameters define a mode of the quantized electromagnetic field. The spatial and temporal coherence properties of the laser photons come from the fact that they are in a single mode, or in a limited number of modes, of the electromagnetic field.

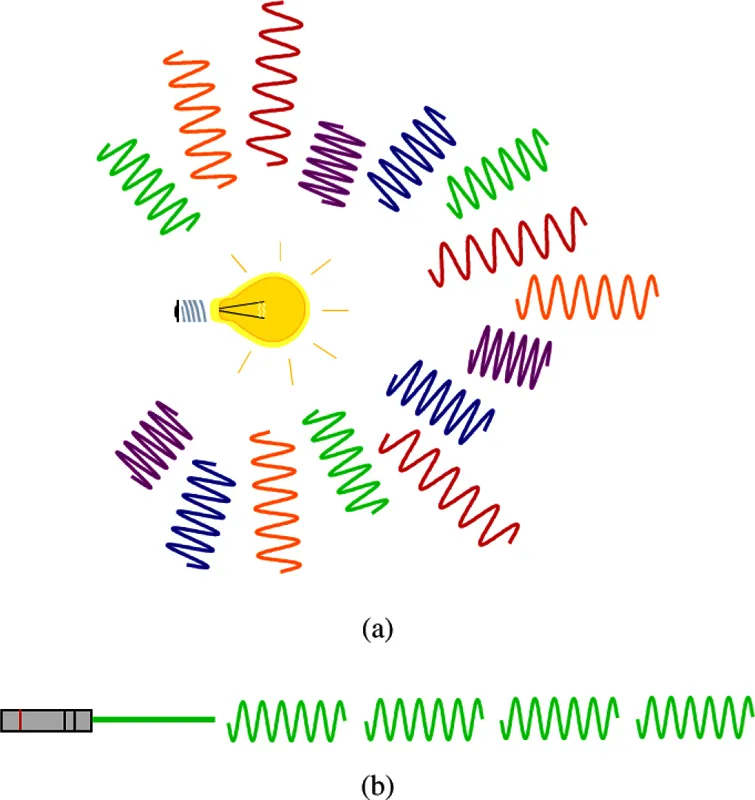

One may have an idea of the behavior of these photons by comparison with pedestrians (see Figure 1.3): photons emitted by a classical ordinary lamp can be seen as a crowd of people, each of them walking at its own pace in its own direction; at the opposite, in a laser beam, they all march in step like soldiers. These laser photons, different from others, are in fact all the same and behave collectively!

1.2. Stimulated Amplification of Radiation

1.2.1. Masers and lasers

The word laser, now commonly used, is the acronym for Light Amplification by Stimulated Emission of Radiation. The laser, which was born in 1960, has an elder cousin, named maser (for Microwave Amplification by Stimulated Emission of Radiation), born a few years before it, in 1954. Both operate on the same principle, but the maser emits an electromagnetic wave in the microwave range corresponding to centimeter or millimeter wavelengths (masers, especially hydrogen maser, are widely used as frequency standards).

The first lasers were called optical masers. As is clear from their denominations, stimulated emission — also called induced emission — plays a key role in the operation of masers and lasers.

Figure 1.3: Photons emitted by a classical lamp (a) have different propagation directions and different wavelengths; photons emitted by a laser (b) all have the same characteristics: direction, frequency, and polarization. In this figure, the oscillations of the electric field, whose spatial period is given by the wavelength, are shown.

1.2.2. Matter, atoms and energy levels

Stimulated emission is a light-matter interaction process which may lead to light amplification. At room temperature, matter is composed of atoms, sometimes assembled together to form molecules. In condensed matter (solid or liquid), atoms interact strongly with each other. In the following, we will restrict ourselves to diluted media, such as a gas, to describe atom–light interaction. In a diluted medium, interaction processes are individual: a single atom is involved and a single photon appears or disappears (more than one photon in the case of nonlinear optics, not studied here).

An atom is composed of a positively charged nucleus and of one or more negatively charged electrons. It has been known for almost a century that the binding energy between an electron and the atom, due to interaction between charges, can only have certain discrete values: the atom energy is quantized.

Figure 1.4: Spectrum of the neon atom, emitted by a tube light.

In 1913, Bohr gave the following description of the interaction between an atom and radiation: the atom can absorb or emit light when it performs a quantum jump between two of its energy levels. Let us call E1 and E2 the energies of the two involved levels with E2 > E1. The energy difference satisfies the relation E2−E1 = hν, where h is the Planck constant, introduced by Planck in 1900 in his study of the blackbody radiation, and ν the radiation frequency. The value of h is 6.6×10−34 J.s, which is very small in our international system of units. The product hν ...