![]()

Chapter 1

The Human Hand and the Robotic Hand

To enable a robotic hand to grasp a target object dexterously, like a human hand, structural features and control functions similar to those in human hands are necessary. Until now, a deep understanding of the human hand has been the province of medical professionals. Researchers in robotics have much to learn from them. This chapter describes the structure of the human hand, its grasping functions, and the structure of the humanoid robot hand called the Gifu Hand. Furthermore, the configuration of a multi-fingered haptic interface called the Haptic Interface Robot (HIRO), a new application for the robotic hand, will be discussed.

1.1. Joints of the Human Hand

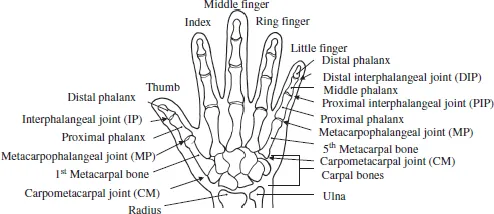

Humans use hands to grasp, squeeze, and manipulate objects dexterously. As shown in Fig. 1.1, the human hand consists of a thumb, four fingers (index, middle, ring, and little finger) and a palm. There are 27 bones in a single hand, as well as muscles, tendons and other associated structures. This section focuses on the bones and joints.

From each fingertip to the base of the finger, there is a distal phalanx, middle phalanx, and proximal phalanx. The metacarpal bone lies between the base of the fingers and the carpal region. Between each phalanx bone lies joints called (starting from the fingertip) the distal interphalangeal (DIP) joint, the proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joint, metacarpophalangeal (MP) joint, and the carpometacarpal (CM) joint.

Fig. 1.1. Bones and joints in the human hand.

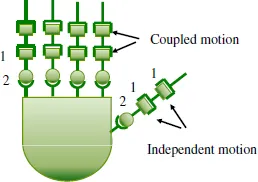

The MP joint has two degrees of freedom (DOFs), adduction/abduction and flexion/extension, along two axes that are approximately orthogonal to each other. The DIP and PIP joints have only flexion and extension with a single DOF. In the case of normal movement, the DIP joint moves in conjunction with the PIP joint; therefore the two joints are considered as a single entity with one DOF. The CM joint of the fingers is considered negligible due to its small operating range. As a result, robotic fingers can be modeled with just three DOFs.

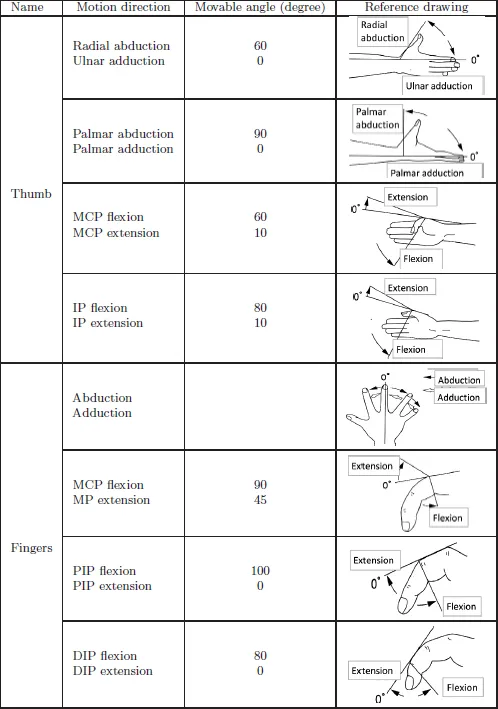

On the other hand, the thumb has only a distal phalanx and proximal phalanx before the metacarpal bone. The joints between the bones are called (starting from the fingertip) the interphalangeal (IP) joint, MP joint, and CM joint. The CM joint has two DOFs; flexion/extension and adduction/abduction. This enables the thumb to oppose each finger — which is called thumb opposition. The thumb MP joint also has two DOFs in flexion/extension and adduction/abduction; however, it usually is modeled as one DOF of flexion/extension due to the limited operating range of adduction/abduction. The flexion/extension of a single DOF is possible for the thumb IP joint. Thus, although the human thumb has five DOFs from the point of view of kinematics, modeling four DOFs may be suitable for the purpose of simplifying a robotic hand. Table 1.1 shows the movable range of the human hand. The radial abduction and ulnar adduction of the thumb are motions in the volar aspect, while palmar abduction and adduction are motions in a plane that is orthogonal to the volar aspect.

Table 1.1 Movable range of the human hand.

Source: Formulation by the Japanese Othopaedic Association and the Japanese Association of Rehabilitaion Medicine, 1995.

There are eight carpal bones in the carpal region of the palm. These constitute the middle carpal joint, although the operating range of this joint can be negligible. The back of the hand can be deployed on a plane when the palm is expanded, and becomes arched when the hand is strongly squeezed. This is called the transverse arch of the hand. It is caused by the mobility of the CM joint that consists of metacarpal and carpal bones, and varies with the various operations of the hand. Though the palm of the human hand has multiple DOFs in reality, it can nevertheless be said that there is approximately one DOF in the transverse arch of the palm.

Taking the information noted above into consideration, the robotic hand will be modeled with around 16–21 DOFs in total. Figure 1.2 is a model diagram of the hand when the finger is set to three DOFs, the thumb to four DOFs, and the palm to zero DOF.

1.2.Hand Features

Many mammals, including whales, bats, and dogs, retain the body structure of the reptilian ancestors of mammals. Hands consisting of five fingers, including the thumb with its distinctive shape, have been specialized to adapt to the environment. Whales have finned bodies in order to live in the sea, while bats are shaped like cloaks so as facilitate flight, and dogs are shaped so as to move easily on land on four legs. All are specialized to their environments. While primates also have five fingers, many have shorter thumbs compared to humans — reflecting how life in the trees (e.g., hanging from branches) is easily accomplished with 2–4 fingers, making the thumb less important. For this purpose, the need for thumb–finger opposition is rare, so a primate’s thumb is not suitable for grasping and manipulating small objects.

Fig.1.2. Human hand model.

The human hand became generalized rather than specialized to a particular environment. Its manipulation capability was improved by the acquisition of an opposable thumb, creating a hand suitable for manipulating various objects. In addition, instead of simply bending in parallel directions, the four fingers can also move toward the thumb.

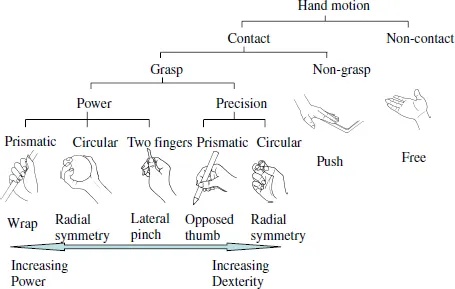

Regarding the motion of the hand, Napier (1956) pointed out that grasps can be divided into two broad categories: power grasp and precision grasp. Gripping a hammer is an example of a power grasp. The fingers clamp down on an object with the thumb creating counter pressure. In contrast, a precision grasp is exemplified by gripping a small ball; multiple fingertips and the thumb grasp the target object. Cutkosky (1989) proposed a grasp taxonomy containing 16 hierarchical structures based on the example of the grasping motion of workers in a machine factory. Kamakura et al. (1998) provided a more detailed analysis than Cutkosky’s (1989). They included non-grasp grips used in daily activities from the point of view of hand function training.

Detailed classifications for grasping are not necessary from the point of view of robotic hand control. Whether there is a physical constraint of contact or no contact between the hand and the object is of greater importance. Figure 1.3 shows a simplified classification of hand functions, broadly classified into contact or non-contact with the object, based on Cutkosky’s (1989) system. In the grasp range shown, dexterity requirements increase from left to right, while power requirements increase from right to left.

Fig. 1.3. Classification of hand functions (Modified from Cutkosky, 1989).

1.3.Tactile Sense

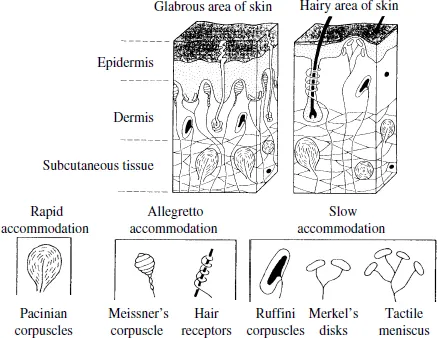

Human skin contains numerous cells known as tactile receptors (Grunwald, 2008). Skin is divided into two areas: hairy and glabrous, as shown in Fig. 1.4. The palm and finger pads are examples of glabrous skin. Glabrous skin is thick, able to retain a palm print and fingerprint, and plays an important role in obtaining information from the outside world through touch. The hairy areas of the skin are non-glabrous, and account for most of the skin. There are many hairy areas on the back of the hand. As seen in Fig. 1.4, from the outside in, both glabrous and hairy areas are divided into three layers: the epidermis, the dermis, and the subcutaneous. The epidermis consists of a papillary layer and stratum corneum that is layer of dead cells. Its thickness at the palmus manus is 0.7 mm. The dermis is a fibrous connective tissue with a thickness of 0.3–2.4 mm.

Receptor cells distributed on the inner part of the skin experience skin sensations such as touch, pain, and heat. The receptors involved in tactile sensing have either a specific structure or a free nerve terminal without a specific structure that spreads at the tip of the nerve fibers. These are called mechanoreceptors, because they react to mechanical stimulation applied to the skin. The mechanoreceptors contain Pacinian corpuscles, Meissner’s corpuscles, hair follicle receptors, Ruffini endings, Merkel’s disks, tactile meniscus, and so on. These are further categorized based on their rates of adaptation into four types: fast adapting type I (FA I), which adapt to velocity; fast adapting type II (FA II), which adapt to acceleration; slow adapting type I (SA I), which respond to velocity and displacement; and slow adapting type II (SA II), which respond mainly to stimuli displacement.

Fig.1.4. Hand skin.

Meissner’s corpuscles are distributed evenly in the papilla of the dermis, and their structure is encapsulated by nerve endings and surrounded by nerve tissue. Corpuscles are 80–150 µm in length and 20–40 µm in diameter. The action potential of the nerve is immediately brought about by morphological deformation of the corpuscles, which quickly reduces and eventually subsides completely. The corpuscles return to their original form when there is no further stimulation. In their position at the front of the dermis, they are suitable for detecting the speed of skin displacement by tactile stimulation. Meissner’s corpuscle can detect crude vibrations of less than 40 Hz, and so are classified as FA I.

Vater–Pacini corpuscles are oval-shaped 1 mm bodies distributed in the subcutaneous tissue; the capsule bodies consist entirely of a few tens of layers of nerve endings. Due to their layered structure, the corpuscles are selectively capable of conveying changes of mechanical stimulation (differential information) and detecting the acceleration of skin displacement. As a result, they respond to high-speed pressure changes and vibration, and their threshold value is lowest with a repeated stimulation of 200 Hz. Vater–Pacini corpuscles are easily excited on contact ...