Epistemological

machines and

protocomputing

Mitchell Whitelaw1 and Ralf Baecker2

In early 2012, a group of researchers attracted wide attention by showing that the logical components of digital computing could be realized using swarms of soldier crabs. The work implements a theoretical “ballistic” model of computing, where logic is enacted through idealized physical interactions, but intriguingly replaces notional billiard balls with swarms of living crustaceans [Gunji et al., 2012]. Aside from the mad poetry of its central premise – a computer made from crabs – this work strikes a popular chord because it addresses a disjunction that we encounter every day. While the computing machines we spend our lives attached to are on the one hand clearly material things – slabs of glass, plastic and electronics – the process of computation itself is completely obscure and apparently immaterial. The comedic spark of a computer made from crab swarms is a product, we suggest, of short circuiting this disjunction, demonstrating computation happening in the world with us, rather than in some hidden abstract realm.

Ralf Baecker’s computational machines address this same question; of how computing happens, and in particular how it operates in the world with us. Like the crab-swarm experiment, Baecker’s artworks resemble no familiar computer: instead of screens and keyboards we encounter strange mechanical contraptions, warbling crystals and networks of strings and levers. As they work these machines enfold us in textures of movement and sound – perceptual traces of a distributed process. Working at a sculptural scale, Baecker emphasizes the physical presence of computing machines; and, in our increasingly digital culture, this is a point worth making. But, as we will argue below, Baecker’s machines also go much further in investigating and transforming computing as we know it.

What kinds of machines are these? If they are in some sense computers, then what can they say about computing? Baecker offers one possible answer, citing the influence of early mechanical automata – what he describes as theatrical, philosophical or epistemological devices [Baecker, 2013a, 2013b]. These are machines for thinking with, devices that demonstrate, enact or provoke forms of knowledge. Baecker contrasts this reflective function with the “utilitarian” computers of our everyday experience; though this is not to say that our familiar computers are any different in their operation. Following Foucault, Jussi Parikka [Parikka, 2013] argues that all media are “epistemological machines” – that they “participate in creating regimes of knowledge across arts and sciences”. We are immersed in a regime of knowledge that our machines reinforce, and so it becomes transparent to us. By physically transforming the computer – and ultimately also transforming computation itself – Baecker’s work prompts us to reflect on these machines and their grasp on the world.

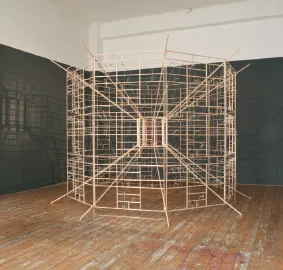

Rechnender Raum

In Konrad Zuse’s 1969 Rechnender Raum – “calculating space” – he posits the notion of a computational universe; that space itself is a computing machine with finite, discrete states [Zuse, 1969]. In adopting Zuse’s concept for his own Rechnender Raum, Baecker creates a literal, sculptural “calculating space”: an open latticework of strings, pulleys and levers manipulating a strange elastic “display” at its core (Figs. 1–3). This computer is literally transparent; the state of the machine is stored in the positions of the mechanical levers arrayed on its outer surface. These levers are linked into modules that form logic gates – the elementary units of digital computing, combining discrete input states into outputs. Where integrated circuits run at millions of cycles per second, this machine updates its state at a more human time scale, once every few seconds. Rechnender Raum thus makes computation physically apparent, “zooming in” on the logical and symbolic operations that underpin our everyday digital computing.

This “open”, mechanical computer recalls some twentieth-century epistemological machines; and these in turn offer some useful counterpoints to Rechnender Raum. The Digi-Comp I and its successor the Digi-Comp II were mechanical computing devices manufactured in the 1960s and sold as toys “to demonstrate the apparatus hidden within the circuits of the giant brains of today” (“Electronic Computer Brain” [E.S.R., 1963]).

Fig. 1. Ralf Baecker, Rechender Raum, Trinitatiskirche Köln, 2007.

Fig. 2. Ralf Baecker, Rechender Raum, detail, 2007.

Fig. 3. Ralf Baecker, Rechender Raum, installation view, Moltkerei Werkstatt Köln, 2007.

Like Rechnender Raum, the Digi-Comp I makes a virtue of being open “so complete operations can be viewed”. The Digi-Comp II was a programmable binary calculator that used marbles and mechanical gates to methodically process input into output. Advertising for these toys reflects their historical and social context, as well as a specific notion of the role and value of computation. “You will be able to add, subtract, multiply – solve problems – solve riddles … think how amazed all your friends will be when you solve problems of missile countdown, satellite re-entry and missile checkout” (“Electronic Computer Brain” [E.S.R., 1963]). The Digi-Comp II (c. 1967) “shows how computers solve math, business, science & other problems” including bookkeeping, summing fractions and “population explosion” (“Digi-Comp II” [E.S.R., 1967]). While this space-age celebration of computing seems charmingly old fashioned, these machines illustrate some foundational characteristics of contemporary computing. The notion of task or problem is fundamental, and the cultural and epistemological value of the computer is linked to the space-age problems it solves. This emphasis is reflected in the spatial and temporal organization of these open machines. Computing here involves providing a “problem” – a set of inputs and a program or logical configuration – and working through a kinetic process that terminates at a solution.

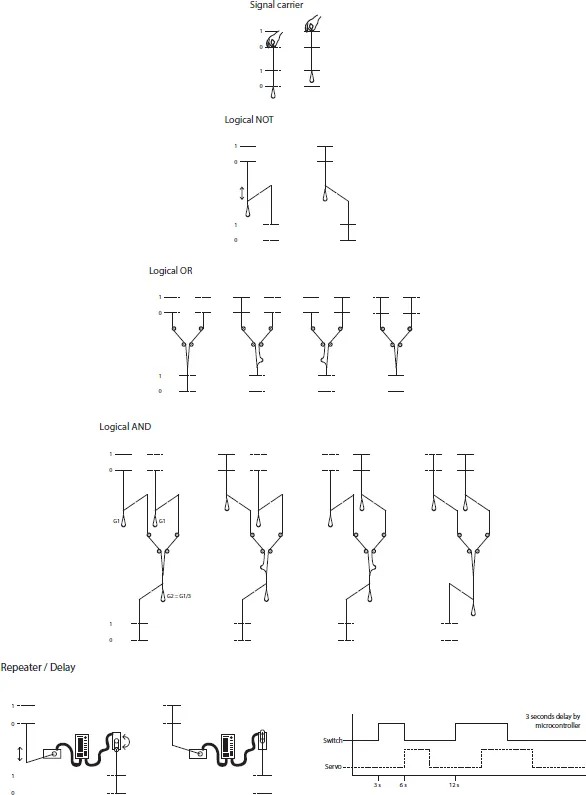

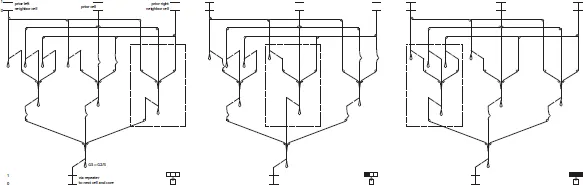

Like the Digi-Comp, Baecker’s Rechnender Raum renders the logical elements (Fig. 4) of digital computing – binary gates – in mechanical form, and exposes computation as a legible, kinetic process. However, there are some striking contrasts in the models of computation at work here, evident in the spatial, temporal and logical structures of these machines. The Digi-Comp machines have a spatial structure that mirrors their input–output configuration. In the Digi-Comp II the rolling marbles enact this transition, trickling through the machine before coming to rest to present the result of the calculation. Rechnender Raum, on the other hand, is in the form of an enigmatic ring; it never offers a human-facing “front” but constantly turns away, and inward, towards itself. Its “output” – a cylindrical net of elastic cords – is kept at a distance, in the core of the ring. As Baecker [2007] writes, “the results of its computations are sent inwards … they are not intended for the viewer.”. Just as it has no front or back, Rechnender Raum never starts or stops: it seems to only carry on, quietly whirring and flipping, strings tightening and becoming slack.

Fig. 4. Rechender Raum, diagram of elementary logic elements, 2007.

These structures come together in the logical architecture of the machine. The torus of Rechnender Raum is made up of nine wedge-shaped modules, each containing three submodules – mechanical gates that process inputs into outputs (Fig. 6). Each submodule is connected to both its neighbouring modules and the core “display”, in an interwoven cascade of logical operations. The process has no edge or end; the structure wraps around on itself, and the bottom-most submodules feed into the top (forming a true torus, in the topological sense). In formal terms, this is a digital computer: binary elements store the state of the whole system; its state changes in a series of discrete time steps, as determined by a fixed, logical “program” and a network of connections. But as a model of computing – as an epistemological machine – it is less conventional. Where the Digi-Comp machines make an earnest effort to reveal the functional power of computing, Rechnender Raum has an ambivalent relationship to its human audience. As Baecker says, it is both open and closed: completely transparent and strictly self-contained. It suggests a form of computing quite independent of human agency; a computer that is not for us – in fact not for anything: it solves no problem, it has no task and it delivers no answer. Yet nor is it idle – it works slowly, tirelessly, in a never-ending process.

In this sense Rechnender Raum and Irrational Computing (see below) are forms of performance: staged actions for us to interpret. The “function” of Rechnender Raum is not to solve a problem, but to perform. Baecker recognizes the theatrical dimension of early mechanical automata, and echoes it in these works. Andrew Pickering’s study of cybernetics proposes the notion of ontological theatre: he argues that the experimental machines of cybernetics – such as W. Grey Walter’s Tortoise and W. Ross Ashby’s Homeostat – stage a “nonmodern” ontology, a particular model of the world focused on action and performance rather than knowledge and interpretation [Pickering, 2010, p. 21]. This theatre both outlines an ontological model – a vision of the world – and actually enacts or performs that ontology. In just the same way Baecker’s Rechnender Raum is ontological theatre. It both describes and enacts a reconfigured computing: one that rejoins us at a human scale, legible and open but at the same time obscure. With the sticks and strings of Rechnender Raum Baecker reminds us, reassuringly, that computers are physical machines; but at the same time he suggests how readily computation peels away into an independent, nonhuman process.

Fig. 5. Ralf Baecker, Irrational Computing, phase-locked loop, 2011.

Irrational Computing

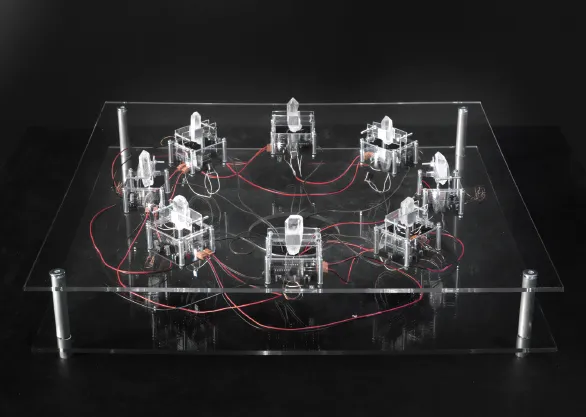

With Irrational Computing (Fig. 8) Baecker mounts a work of ontological theatre that seeks out the edges and origins of computing machines; once again the result is not so much an exposition of computing, as a reconfiguration. The prerequisite for this reconstruction is a deconstruction, a stripping down; we can see this in Rechnender Raum, where Baecker implements logic gates with levers, weights and strings. In Irrational Computing Baecker turns to crystals and electronics – the mineral and technical substrates of conventional computing – but seeks out their idiosyncrasies and instabilities. He creates modules based on fundamental digital components such as transistors and clocks, but at a sculptural scale: a scientist’s workbench on which a weird, emergent system – a not-quite- or not-yet computer – sits talking quietly to itself.

Fig. 6. Rechender Raum rule 110 (Wolfram) cellular automaton implementation (matching patterns), 2007.

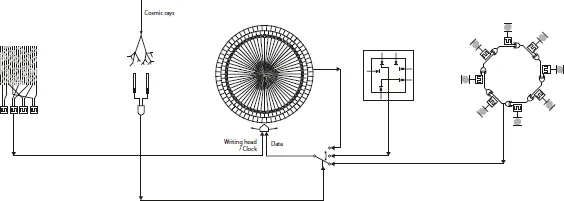

Fig. 7. Irrational Computing, Schematic, 2011.

Irrational Computing is made up of five “modules” (Fig. 7) – transparent constructions of electronics and crystals, glimmering, clicking and buzzing. Each of the modules in the work is an independent electromineral unit; these are interlinked to form the chaotic ensemble of the work as a whole, which Baecker terms a “primitive macroscopic signal processor”. At the centre of the installation sits Module I – the “display”: a dark lump of silicon carbide encircled by probing arms. (Fig. 10) An array of 64 iron electrodes applies pulses of current to this crystal, triggering tiny flashes and clicks, like sparks of lightning within a thunderhead.

Module II is the coincidence detector: two parallel glass tubes (Geiger Müller tubes) sit atop exposed electronics; four tiny light-emitting diodes (LEDs) blink and chirp intermittently. Here Baecker recreates a device invented in the late 1920s to detect the incidence of cosmic rays. In 1930 Bruno Rossi (see [Bonolis, 2011]) improved the design by adding an electronic circuit to automatically detect coincidences between the two tubes. In doing so, Rossi also invented the first el...