![]()

Singapore 50

![]()

A Community at a Crossroads:

The Perspective of a Community Leader

Azmoon Ahmad

Chairman

Association of Muslim Professionals, Singapore

Over the last 50 years, the Malay/Muslim community in Singapore has seen numerous programmes rolled out to empower it by intervening in key areas of education, employment, youth, gender, family and socio-religious life of Malay/Muslims. A number of the Malay/Muslim organisations and institutions addressing Malay/Muslim issues were set up as early as the 1950s.1

In the last two decades in particular, there have been constant discussion and debate about the community’s progress through platforms like the National Convention of Singapore Muslim Professionals, which has been held at the beginning of each decade since 1990, aimed at charting the community’s strategic directions.

The Malay/Muslim Community’s Achievement

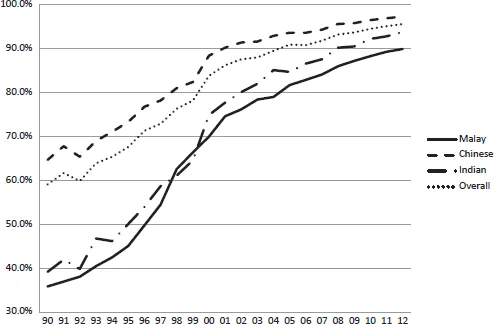

The Malay community has made significant educational and employment gains. Minister-in-Charge of Muslim Affairs, Dr. Yaacob Ibrahim, described the community’s achievements during his speech at the Hari Raya Get-Together in August 2013 as having “scaled many peaks of excellence” (Ibrahim, 2013).

Indeed, the accomplishments of the Malay/Muslim community are remarkable if one was to consider certain characteristics which make its progress within the larger Singaporean society a challenge. Despite lagging for decades in terms of median household income, which limits the funds a Malay family could allocate to their children’s education; and despite the lower educational attainments of Malay parents, which constrains their contribution to their children’s academic pursuits, the community continued to improve their educational and occupational profiles. More are going to post-secondary institutions and better qualified Malays are entering the workforce.

Given the community’s ability to thrive under less than favourable conditions, there is cause to remain positive about the social, economic and political affairs of the community as 2065 approaches. It is however worth highlighting potential pitfalls as the community navigates an uncertain future over the next 50 years.

Percentage of P1 Cohort Admitted to Post-Secondary Institutions

Source: Ministry of Education, Singapore

Redefinition of Success and Impact on Community

As the community was making progress, at the national level, success continued to be redefined, bringing about both benefits and challenges to the community.

On the one hand, the move towards according greater prestige for talents and skills that extend well beyond academic success led to the creation of multiple avenues for achieving excellence, which the community could capitalise on and which gives the less academically inclined a chance at doing well in life. Self-help groups conducting education programmes began to introduce fresh initiatives, offering, for example, experiential learning programmes to young children to nurture creative talents.2

On the other hand, the community’s aspirations are by and large geared towards achieving academic excellence. Years of efforts at inculcating the importance of academic achievements made it difficult for both Malay/ Muslim organisations and Malay/Muslim parents to shift gears and adapt to the broader definition of success. Passing examinations and getting into good schools remain the immediate concern, hence the failure to fully appreciate a system of multiple pathways.

There was no clear indication that, since the introduction of the Ability-Driven Education (ADE) paradigm in1997 (Lee, 2001), the Malay/Muslim community is taking advantage of it or that it complements the cultural or socioeconomic attributes of Malay/Muslim students. But the new landscape is here to stay and the push towards a system that prizes skills and talent is likely to gain momentum as 2065 approaches.

Work-and-Study Initiative

More recently, during his National Day Rally 2014 speech, Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong talked about work-and-study paths for non-graduates. Citing the stories of several Keppel employees who rose through the ranks to land senior managerial positions, Mr. Lee conveyed a clear message that pursuing higher qualifications which are irrelevant to one’s career is not the way to go, assuring instead that opportunities to obtain higher qualifications that are pertinent to one’s ability to take on greater responsibilities in one’s job will remain open throughout one’s career path.

With the announcement by Mr. Lee, the drive to value skills and talent may gain traction in the long run. Changes are expected to follow in the areas of education and employment, based on the recommendations of the ASPIRE Committee which the government accepted.3

Employment Challenges of a Young Population

The emphasis on education is particularly important to the community not only because it is a conduit for social mobility but also because of its relatively youthful population (Singapore Department of Statistics, 2013), making it imperative to look into how best to equip the young to make telling economic, social and political contributions in the next 50 years.

As Singapore pursues its population growth policies and its vision of a global city, there will be a multifaceted impact on the community. Immigration of talents and high-net-worth individuals (HNWIs) will constantly infuse renewed vigour into Singapore’s drive to maintain its competitive edge. Jobs will continue to be created, benefitting Singaporeans and the Malay community.

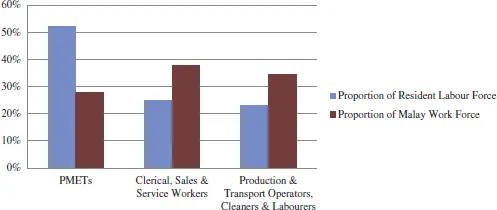

However, it is worth noting that the share of PMET jobs have increased to 52.7% in 2013 from 45.4% in 2003 (Ministry of Manpower, 2013) and will continue to grow in the next 50 years. It can be projected that new jobs created will be largely in PMET positions while the share of non-PMET employment categories will continue to shrink.

In the lower-skilled job categories, declining emphasis on the paper chase and assurance of work-and-study opportunities may slow down the pace of educational attainments made by the Malays, perpetuating their overrepresentation in the segment of workers with secondary and post-secondary (non-tertiary) qualifications. While there will be those who will advance into managerial and professional positions from lower starting points, questions remain about the chances of the rest scaling the rungs of the income ladder against a backdrop of competition from low-cost labour and high income inequality.

With only 28% of Malays in PMET positions (Singapore Department of Statistics, 2010) and the perpetuation of non-tertiary qualified Malays entering the workforce, the prospects of keeping pace with how the occupational composition at the national level is changing do not appear bright.4 Hence, there are real concerns about whether the Malay community will face an employment crisis in the next 50 years.

The work-and-study initiative is however beneficial to the community in the sense that, considering that a significant proportion of post-secondary Malay students are in Institute of Technical Education (ITE), the ASPIRE Committee’s recommendations promise career paths for ITE graduates, thus making it possible to nudge them towards higher income brackets.

Occupational Composition (Resident Labour Force 2011, Malay Work Force 2010)

Sources: Census of Population 2010, Department of Statistics, Singapore; Labour Force in Singapore 2011, Ministry of Manpower

Immigration and Emigration of Malays

The improved outlook for the community’s ITE graduates notwithstanding, augmenting the educational and occupational profile of the Malay community is likely to remain a major challenge. It is unlikely, for instance, that there will be a substantial inflow of Malay or pribumi talent from Southeast Asia, as Prime Minister Lee shared during his National Day Rally speech in 2010. Although he gave assurance that efforts will continue and that the government will not allow immigration to upset the racial mix, the rate of Malay immigration is unlikely to change sufficiently to have significant economic, social or political impact on the community in the next 50 years.

On the contrary, the likelihood of Malay emigration is greater, particularly among those who are better educated and higher skilled. Perceptions of discrimination and keen competition for employment opportunities will be among the primary motivators for seeking greener pastures abroad. The human capital flight will not augur well for the community’s continued socioeconomic progress.

Income Inequality and the Underclass

The social landscape is expected to be harsher as population policies contribute to the growth of the middle class, sparking shifts in income distribution that aggravate income inequality. More households, of which many will be Malay ones, will struggle to cope with inflation as the threat of a permanent underclass developing looms not only over the community but also on a national scale. Social researchers have estimated that between 10% and 12% of resident households are unable to meet expenses on basic needs (Donaldson et al., 2013). The problem is likely to become more acute as Singapore heads towards 2065.

The government has taken a cautious approach in ensuring that social policies are calibrated so as not to undermine the values of self-reliance and resilience but it has been improving social safety nets over the years, with more measures being announced during the recent National Day Rally speech.

Affirmative Action

The improvements to social safety nets notwithstanding, there may still be a need to institutionalise affirmative action for society’s disadvantaged, not one that is modelled after the much-criticised Malaysian National Development Policy5 but one that promotes a diverse spread of people of various backgrounds in the workplace. Such affirmative action can be implemented without undermining the principles of meritocracy as Minister for Foreign Affairs and Law, K. Shanmugam, pointed out (Chia, 2009). He cited the example of former US Secretary of State, Dr. Condoleezza Rice, who benefited from Stanford University’s selection criteria, becoming a professor at the institution. He said, “Assuming 10 people made the cut-off, try to look for some who are also from the Malay community.”

Social Divide

It is of utmost importance that bold measures are taken to address economic problems as they could contribute to social tensions, pitting not only one social class against another or natives against naturalised Singaporeans but also, within the community, one group of Malays against another. This intra-community divide could be in the form of increased isolation of well-to-do Malays from the struggling ones, the emergence of subcultures that are at odds with mainstream Malay/Muslim culture, the polarisation of socio-religious orientations as prevailing socioeconomic conditions give rise to suspicion of capitalism and modernism, all of which could undermine efforts to sustain the community’s socioeconomic progress.

The Singaporean Identity

Conversely, the diversity that immigration introduces may address a thorny issue: there has been persistent disquiet within the community that employment and workplace discrimination have debilitating effects on the job opportunities and prospects of Malay workers. An increasingly diverse population will bring about a new social order in the next 50 years, which may see the Singaporean identity of Malays emerging more strongly than their ethnic identity, thus countering negative stereotypes of the Malay worker. They will be part of the Singaporean core in the workforce (Faizal, 2013).

A stronger Singaporean identity will address the longstanding issue of the position of the Malays in the Singapore Armed Forces. More Malays are expected to hold what have hitherto been considered sensitive appointments, thus countering perceptions that Malays are unable to land key appointments in government institutions by virtue of their ethnicity.

Conclusion

Looking into the future, the outlook for the Malay/Muslim community may not be very rosy but, with the right initiatives, the strengths of the young could be harnessed to hedge against the risks posed by an uncertain future socioeconomic landscape. There have been many positive developments in the community, such as making educational and employment progress despite beginning from lower starting points. They point to the community’s resilience in navigating adverse socioeconomic terrains to achieve desired outcomes. There is therefore a valid reason to remain optimistic about the community’s future.

Note: Special thanks to Abdul Shariff Aboo Kassim from the Centre for Research on Islamic and Malay Affairs (RIMA) for his contributions to this article.

References

Chia, S. A. (2009). No Quotas But a Diverse Spread of People. The Straits Times. Retrieved July 2009 from http://news.asiaone.com/News/the+Straits+Times/Story/A1Story20090706-152905.html.

Department of Statistics, Singapore. (2010). Census of Population 2010: Statistical Release 1, Demographic Characteristics, Education, Language and Religion, pp. 76. Singapore: Department of Statistics.

Department of Statistics, Singapore. (2013). Population Trends 2013. Retrieved June 1, 2014 from http://www.singstat.gov.sg/publications/publications_and#x005F;papers/population_and_population_structure/population2013.pdf.

Donaldson, J. A., Loh, J., Mudaliar, S., Md Kadir, M., Wu, B., and Yeoh, L. K. (2013). Measuring Poverty in Singapore: Frameworks for Consideration. Social Space. Retrieved December 18, 2014 from http://ink.library.smu.edu.sg/lien_research/110.

Ibrahim, Y. (2013). Speech by Dr. Yaacob Ibrahim, Minister for Communications and Information and Minister-in-Charge of Muslim Affairs, at Hari Raya Get-together, 23 August 2013, 8.00 pm at Sheraton Towers Singapore. Retrieved February 1, 2014 from http://www.news.gov.sg/public/sgpc/en/media_releases/agencies/mcicrd/speech/S-20130808-1.html/.

Lee, C. K.-E. (2001). Ability-Driven Education in Singapore: Recent Reform Initiatives. National Institute of Educ...