![]()

Chapter

ONE | |

| | The Foundations of Personalization |

As the digitization of life proceeds with seemingly exponential progress, we continually find ourselves in an ever changing cultural landscape, where each day the amount of new information recorded is greater than all of the world’s recorded information prior to the digital age, where the average citizen of nearly all nations has unprecedented access to knowledge, entertainment and opinion, and of course where those same citizens are exposed to hundreds of advertisements a day on screens both stationary and mobile.

We find ourselves in a world where social life increasingly means digital life, and where success in business and marketing require advanced capabilities to access and interpret data. In short, we’ve crossed the horizon into a world where it can be argued that culture (i.e. work, arts and entertainment, customs, habits and pastimes) has largely become a product of information technology, and that correspondingly, information has become the core of culture in the developed world.

Living in a technologically and digitally driven world means living with constant change. In the 20th century, the economic and cultural base of the developed world transformed from being agriculturally (and land) based to manufacturing and technology based over half a century, with the Second World War finally cementing the rise of the technocrat over the gentry as culture’s new elite. The transformations that have occurred as developed culture has then shifted from capital intensive analog technology to skill and information intensive digital technology have come more and more rapidly, and many businesses are still trying to catch up with the changes in technology and society that have come at them over the last two decades.

The continual development of information technology and applications arises from a human drive to continually expand both our knowledge and convenience, a drive that has been at the core of advancement in science and technology for centuries. In the middle of the 20th century, the study of such advancement in communication technology was taken up by a professor of communications at the University of Toronto in a way that forever changed our understanding of the relationship between media and society.

Given the breadth and depth of any individual’s exposure to media today, it seems inconceivable that the phrase “Media” and the concepts associated with it would at one time have required an introduction and development within popular thinking, but in fact there was such a time not that long ago, and the man who made the introduction was Professor Marshall McLuhan.

McLuhan’s 1965 book Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man introduced the concept of Media where previously there had simply been notions of independent communication technologies such as ‘the press’, ‘television’ and ‘advertising’ which were recognized to synthesize into a single unit in practice, but were nonetheless typically evaluated individually with regards to their impact on culture.

McLuhan observed that these and many other information and communication technologies and practices not only work together and proceed from one another, but that in doing so they actually extend the perceptual power of individuals and mediate communication and thinking in ways that significantly influence culture and human affairs; thus his application of the term Media to these mediating ‘extensions of man’.

Perhaps the most lasting convention introduced by McLuhan (and the most useful for the subject of this book) is the notion of “hot” and “cool” mediums, or elements of culture. Very few people wonder who should be credited for coining the use of ‘cool’ in social context, e.g. a ‘cool’ new band or the ‘cool’ kids at school, since the expression seems to have always been a part of the vernacular. Equally, the idea of a ‘hot’ new sound or a person with a ‘hot’ body are commonly used in American parlance without consideration of origin. Today, these notions of “cool” and “hot” seem natural in the ways they are applied, but it was just as recently as the beginning of the Cold War that Marshall McLuhan observed that different media exerted different influences on people’s perceptions and engagement with those media, and classified those media into “hot” and “cold” categories.

McLuhan’s theory has held up incredibly well into the early 21st century media environment, and still provides an excellent framework for understanding the influence of mediated information on culture, and the countervailing response of culture in the subsequent development of new information technology. Everyone wants their content to be “hot”, “sticky” and “viral”, and these metaphors for information owe much to McLuhan’s understanding of how people engage with messages in media. McLuhan’s thinking is worth consideration by anyone interested in the science of marketing communications, and will be explored in detail in Chapter 9. But to begin with, we’ll first boil down the application of McLuhan’s ideas to marketing to a fundamental principle — the message is either relevant in the receiver’s current context, or it is not.

1.1The New Business Value: Analytics Increase Relevance

In 20th century marketing, messages from the brand were thought to be uni-directional, and consumer interaction with these messages was thought of as passive receipt and absorption of the message. Digital communications turned that idea on its head. Digital communications are multi-directional, as consumers have the capability to respond and interact directly to and/or about the brand through both shared and owned media channels. This interaction between brand and consumer or by consumers about/around a brand in all digital channels is commonly referred to as “engagement”, and effective engagement is the objective of all digital marketing. Engagement resulting from digital marketing may be as simple as clicking on a link or liking/sharing content (and thus passing it along through a network), or it may be more involved, such as returning to a brand’s digital experience, going deeper into content and tools, adding their own new content, attending an event, completing a form, making a purchase or sharing a referral.

When it comes to engagement, one rule stands out over all others: relevance drives results. We are no more likely to engage with activities and conversations that have no appeal or value to us in digital than we are in the real world. In fact, digital gives us much better ways than we have in real-life to filter out irrelevant and uninteresting content. Digital also gives us much more content to filter than we face in real-life, which for most users creates a high threshold between what is potentially viewable for them and what actually elicits engagement.

This returns us to the largest problem that the digital marketer faces today: how do I deliver content around my brand that is relevant enough to drive engagement in the user’s current context? The answer to this is of course through the application of data and analytics to drive highly relevant, contextual targeted content and adaptive experience.

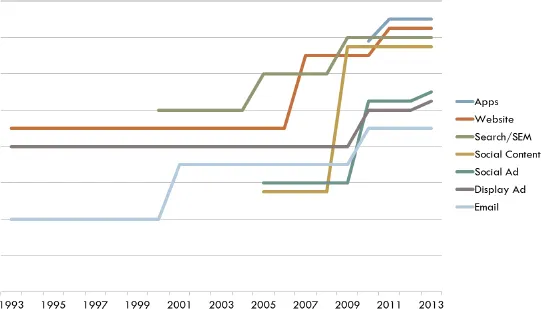

The figure below tells a story about the rise of relevance in digital communications channels over the past two decades.

As we see in Figure 1.1 in the earliest days of mainstream digital communication, marketing was conducted through email, display advertising and websites. Of course, the dawn of email marketing brought the immediate dawn of spam, since in the early days, simply having an email address qualified you for targeting by anyone who could get that email. In early digital marketing, display advertising was made more relevant than email by virtue of some occasional effort to align advertising with the content of the page on which it was advertised, at least by marketers who didn’t want to throw their digital budget down a black hole. And marketing on websites was the most relevant content on the web for those exposed to it since they were qualified to see it based on having sought it out.

Figure 1.1 The Rise of Relevance

Search marketing arrived on the scene in earnest in 1999 to take the top position for delivering relevant marketing content through algorithms that matched expressed interest or intent with digital content results. Being based on explicit interest cues and algorithmic matching of content to those cues, search has remained toward the top of the relevance ladder ever since, being surpassed recently only by content that has interest cues, algorithmic content targeting and memory of user history in a more specific context than the blank page of a new search. However, Google’s interest in having more user context data from across all platforms will likely see the return of “predictive” search (exhibited currently in the Google Now application) as the most relevant form of content delivery around any users immediate content needs in context.

What Figure 1.1 shows us — beginning with search then extending to social content, social ads and eventually lifting all boats — that increasing data about context and algorithms for matching content with context are helpful in delivering relevance. But where is this data, and how do we use it to discover what is relevant, and apply that understanding to driving results?

1.2Introducing the “Demand Chain”

A company’s supply chain and the practice of supply chain management is critical to that company’s ability to produce and deliver its goods to its customers. An organization’s supply chain is the linkage of material, processes and people that proceeds from the initial procurement of the raw materials needed to product a product, all the way through production to the final delivery of that product to the end customer. Without careful management of the supply chain, among other problems, materials required for production might not be available when needed, warehouses could be overflowing with un-needed raw material or finished product, or more product than needed could be produced to sit on shelves in stores without buyers. Supply chain management begins with projections around the demand for products, then puts into motion all of the gears required to produce and then distribute the right amount of product in the right places at the right time based on that demand.

While a complex array of production inputs, outputs and logistics provide the material for supply-chain management, it is the projection or forecast of demand from the market that provides the impetus. If the forecasted demand for product is incorrect, then the best a highly effective supply-chain management process can do is try to adjust to the estimating error once it becomes apparent.

Creating perfectly precise demand forecasts is nearly impossible, so producers of goods and services have options. If the good is something packaged and sold in a store, then a target for sales is set, and production (in actual units or in production cost-to-profit ratio for something like software) is run to that target. Once produced, the product is put up for sale in stores and/or online. Once the product is up for sale in some location, the supply chain has done its job until more product is needed — which can be quickly for made-to-order goods or services. However, once the product is up for sale, the product has entered the “demand chain” — a less recognized and less understood area of the marketing equation.

If the supply chain is the process that pushes a product out to where it can be bought, the demand chain is the counterpart process through which the customer ultimately pulls the product into their basket. Similarly, if the supply chain is the process that produces product supply, then the demand chain is the process that produces demand.

1.3The Customer Journey

While marketing strategy and marketing communications tries to understand and tap into the demand chain, it is a common and disadvantageous mistake to think that marketing drives the demand chain, and is the source of product demand. Demand for products starts with a need or desire in a consumer. It is very true that advertising applies psychology to evoke needs and desires, but it is also true that most goods also fulfill an actual need or demand. Advertising can be used to cultivate the perception of a certain brand of clothing as more sexy or sophisticated than another, but the demand for clothes was already there. Demand also requires a stimulus to buy — I may be exposed to advertising that guides me to fully perceive a brand as tied to some characteristic or quality, but perception is not purchase. To become a customer, there must be some kind of trigger prompting me to buy something in that product category. Only then will my pre-established perceptions of the characteristics of various options begin to matter.

So, the demand chain begins with a “trigger” to consider a purchase. This can be as simple as running out of toilet paper, or as complex as recognizing the need to determine a care plan for an aging parent. The most traditional concept of the consumer path to purchase (along the demand chain) envisioned marketing as a funnel that brought the consumer from awareness, to interest, to desire and then finally to action, or purchase.

This way of thinking of customer engagement has guided generations of marketing planners and marketing campaigns, with no expense spared on awareness and branding campaigns based on the idea that more volume at the top of the funnel has to translate to more volume out the bottom of the funnel. Of course, the funnel was never a funnel as there was never 100% retention of what went into the top. Instead, it was more of a sieve, with much of what went into the top spilling out before it ever reached the bottom. Thus, the idea that increasing volume at the top of the funnel would increase sales at the bottom has never been guaranteed. In fact, depending on how many and how large the holes in the process of moving consumers from awareness to purchase, there has always been strong potential to waste huge amounts of time and effort moving people into the top of a process from which they would immediately fall out.

This recognition of prospect attrition throughout the traditional “funnel” to purchase and the question about how to decrease such attrition necessitated a new way of thinking about the path to purchase. In 2009, McKinsey Consulting introduced the idea of the Customer Decision Journey, which has subsequently become the new standard in thinking about the path consumers take from awareness through purchase and importantly, even after purchase. Since its introduction, it has gone through several stages of evolution and refinement, such as the version of the journey we will reference throughout the pages of this book.

Figure 1.2 takes the original notions of the McKinsey Customer Decision Journey and adds two additional dimensions: the role of external “life events” as triggers to the customer decision journey, and the interaction points between customers on the journey and data about those customers.

The process begins on the far left with a “life event”, which is some piece of context that provides the impetus to take action in our product category. Life events are diverse, and relevant life events for any business will vary based on the nature of that business. Life events range from major events such as marriage, a new job, a new house or the birth of a child to everyday events such as hosting a party or even just having time for lunch, reaching the weekend, getting off from work in the afternoon, or needing toilet paper. Life events do not need to be major in order to be significant triggers for the customer decision process. The size and scope of the life event is not what matters in itself. What matters most is that we, as marketers, are cognizant of the fact that there is always an external context to a customer’s entry into a decision journey — that the customer has a life outside the decision process, and that something about that life brought them in to the decision process. Understanding this, the marketer should treat every life event as something important enough to their customer to trigger the expenditure of thought and energy through the decision process, and should of course recognize that the more significant the life event, the more significant the customer problems, objectives a...