![]()

Chapter 1

Fundamentals of High Temperature Oxidation/Corrosion

A.S. Khanna

Department of Metallurgical Engineering and Materials Science

Indian Institute of Technology

Mumbai 400076, India

Material degradation at high temperatures takes place due to loss in mechanical properties with increase in temperature as well as due to the chemical interaction of metal with the environment. This chemical interaction is further sub-divided into oxidation, sulfidation, and hot corrosion. While oxidation leads to the formation of oxide, which can be deleterious if the oxide is fast growing and spalls extensively, however, if the scale formed is adherent, thin and slow growing, it provides protection to the base metal or alloy. Sulfidation is a much severe degradation process and several times faster than the oxidation. In many industrial environments, it is a mixed gas environment, leading to oxidation and sulfidation simultaneously. Hot corrosion is another degradation mechanism which is even more severe than the oxidation and the sulfidation. Here, oxidation/sulfidation occurs in the presence of a molten salt on the surface of the substrate. Related issues, such as role of defect structure, active element effect and stress generation, during oxide growth process, have also been discussed. Finally, a guide to material selection for high temperature application is presented.

1.Introduction

Corrosion eats away several billions of our hard earned money in replacement, repair and maintenance of several components, parts or the whole equipment, due to leakage, catastrophic accidents or due to plant shut down. One of the main reasons of corrosion of metals and alloys is the reaction with environment around it, which may be natural atmosphere, or the liquid or gaseous environment around the metallic component. Many corrosion failures occur at room temperature for which some electrolyte is necessary. However, at high temperatures, the corrosion occurs due to direct reaction of metal with its environment. For example, steel exposed to oxygen at room temperature does not cause any reaction of oxygen with metal, however if the same steel is exposed to oxygen at 600°C, the steel reacts with oxygen, forming various iron oxides on the surface. Thus, the main criteria of corrosion of a metal under the gaseous environment at high temperature is its tendency to form an oxide or other products, for which the free energy of the formation must be large negative. For example, for a reaction,

ΔG° should be large negative. ΔG° is the standard free energy for the formation of the oxide MO2. The free energy can be related to partial pressure of oxygen using a standard equilibrium condition by

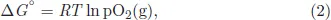

where pO2(g) is the partial pressure of oxygen at a temperature T and R is the gas constant. This is a very useful equation from which we can get the dissociation pressure of oxygen at any temperature if we plot ΔG° versus temperature. Also, we can get the relative stability of various oxides of several metals in the periodic table. Further, using this table, one can read the dissociation pressure of various metals at different temperatures and can also find out the minimum partial pressure, required for a metal to oxidize at various temperatures from a well-designed nomo-graphic scale around the ΔG° versus T plot. This diagram is well known as Ellingham diagram or Richardson diagram and is shown in Fig. 1. There are three nomo-graphic scales, where one can read directly, the pO2(g), ratio of p(H2/H2O) and p(CO/CO2) which are related to pO2(g). Details of this diagram can be seen in Ref. 1

Fig. 1. Ellingham/Richardson diagram.1

Ellingham diagram, therefore, defines the oxidation process due to the basic thermodynamic criterion. It simply tells whether a metal can be oxidized or not at a particular temperature and at a given pressure of oxygen. The biggest limitation of the Ellingham diagram is that it cannot predict how fast or slow the oxidation process is. Therefore, another important aspect of high temperature oxidation is the kinetics of oxidation.

2.Kinetics of Oxidation

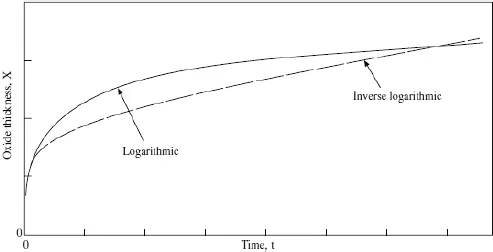

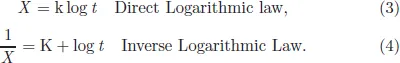

Oxidation kinetics is the engineering requirement of high temperature oxidation. Every engineer requires the lifetime of a metal in terms of its oxidation resistance. Hence, it is very important to predict the life of a component operating at high temperatures. Kinetic behavior basically means the variation of oxidation rate with time. This variation can be logarithmic, parabolic or linear with time, giving rise to three important kinetic laws: logarithmic, parabolic, and linear kinetics, respectively, as shown in Figs. 2 and 3. Logarithmic oxidation kinetics predicts very quick initial reaction, followed by almost no reaction. Based upon how slowly the rate subsides after initial fast reaction, the logarithmic kinetics can have direct or inverse behavior of scale thickness versus time. This law is followed by almost all metals when they are oxidized at low temperatures and low pressure or for noble metals at high temperatures. The kinetic equation of the two laws is written as

Fig. 2. Showing logarithmic kinetics.

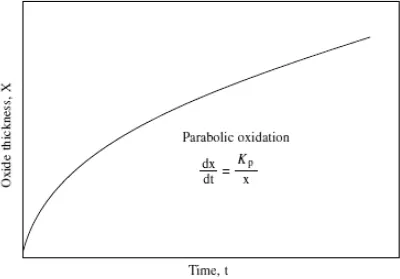

Fig. 3. Showing parabolic kinetics.

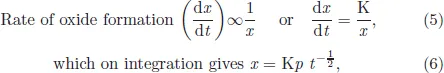

The most important law which is usually followed by important high temperature metals and alloys is parabolic law. This law predicts that the rate of oxide layer formation is inversely related to time, which means that as the time increases, the rate of scale formation is continuously decreasing. As a matter of fact, every engineer would like to choose a metal whose oxidation rate decreases with time. Basic reason behind this law is that here oxidation is under diffusion control. It is assumed that the oxidation occurs either by the diffusion of metal ions from metal substrate towards oxide gas interface to react with oxygen, or oxygen ions diffuse through the oxide layer, reach the metal/oxide interface and react with metal. With time, as the scale growth takes place, diffusing species requires longer time to diffuse thicker oxide layer. The parabolic kinetics is usually written as

where x is scale thickness, Kp is parabolic rate constant and t is time.

The third law is the linear law, according to which, the rate of oxide scale formation is directly proportional to time, which means the reaction is so fast that the metal reacts with oxygen, as soon it comes in contact with the metal. Usually, no metal which follows linear kinetics can be used for any engineering component. In high temperature oxidation, indication of linear law basically means some kind of catastrophic reaction, resulting due to the cracking of oxide scale or other failures such as scale delamination or spallation of oxide. For example, when a metal, which is showing parabolic behavior for a very long time, suddenly shows linear behavior, it indicates some defect in the protective oxide layer, cracking or delamination.

3.Isothermal Versus Cyclic Oxidation

One of the very important criteria to select material for high temperature oxidation resistance is the stability of the oxide layer formed. It is expected that during thermal cycling, the oxide remains intact on the surface without any cracking or spalling. This criterion can be met only if the metal/alloy passes the cyclic oxidation test.

Usually, the oxidation tests are carried out at a fixed temperature and weight gain is measured as a function of time from which kinetics are predicted. This situation of testing is called isothermal condition and there is very little chance metals show cracking or spalling during isothermal oxidation. In actual practice, many high temperature components are heated for certain time, followed by bringing them to room temperature, heating again and followed by cooling and heating several times. A set of heating and cooling is called one cycle. Depending upon the design of a material and its requirements, type and number of cycles are selected and tests are carried out for such number of cycles. For an excellent oxide for high temperature application, the oxide layer must remain intact throughout the test. The reason why oxide scale spalls during thermal cycling is due to release of thermal stresses generated due to sudden cooling from high temperature. Following equation gives the stress generated when an oxidizing sample is cooled from a high temperature T2 to a lower temperature T1.1

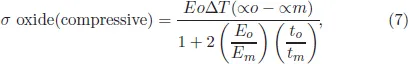

where σ is the compressive stress due to to thermal cycling, Eo and Em are, respectively, the young’s modulus of oxide and metal with to and tm as respective thicknesses and αo and αm are the coefficients of thermal expansion of oxide and metal, respectively, and ΔT is the temperature drop from T2 to T1.

One of the precautions to avoid spalling or cracking during thermal cooling is to carry out slow cooling, which does not generate enough stresses and thus oxide remains intact. Another method to make spalling resistant alloy is by addition of small concentration of active elements such as yttrium, cerium or lanthanum. These elements make a strong oxide to metal bond by one or more of the various theories, pegging, enhancing plasticity of scale, etc.1

4.Oxidation of Pure Metals

A pure metal can form a single oxide or multiple oxides when oxidized at high temperatures. Ellingham diagram guides the partial pressure of oxygen required for a particular type of oxide formed on a metal. The oxidation process is relatively simple when a single oxide layer is formed. After knowing the type of oxide, it is possible to estimate the diffusing species, metal ion or oxygen, which drives the oxide formation. Let us take the example of the oxidation of a pure metal like nickel. Ni, on oxidation forms a single oxide NiO, which is a p-type oxide, thus the Ni++ ions are main diffusing species from the nickel substrate to oxide/gas interf...