![]()

Chapter 1

Fundamentals of Audio Amplification

1.1Introduction

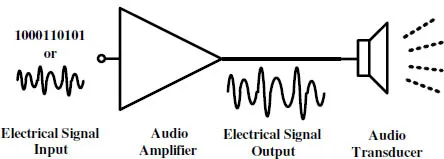

The audio power amplifier provides the power to the loudspeaker in a sound system. In detail, the audio amplifier is a device that takes an input electrical signal representing the desired audio information, amplifies it, and delivers it to a transducer that converts the electrical signal back to audio as described in Fig. 1.1.

Fig. 1.1 Audio amplifier operation.

Nowadays most of portable devices in the market process the audio signal content using an audio processor. The audio processor sends the signal to the audio amplifier using a serial protocol such as Time-division Multiplexing (TDM), Pulse-density Modulation (PDM), or Inter-IC Sound (I2S). Most audio amplifiers include a serial interface to communicate with the audio processor. This communication capability allows added functions such as sound equalization, volume control, among others to the audio amplifier. The received audio signal is either converted to an analog signal using a Digital-to-Analog (DAC) converter or processed digitally to be applied to the audio amplifier. Note that the input of the audio amplifier can be continuous in time and amplitude (analog signal), or discrete in time and amplitude (digital signal), but the output signal applied to the audio transducer must be an analog signal.

Audio amplifiers have a history extending back to the 1900s, and with hundreds of thousands amplifiers being built nowadays, they are of considerable economic importance [1]. They can be found in many systems [2] such as televisions, radios, phones, cellular phones, hearing aids, portable audio/video players, tablets, desktop, notebook and netbook computers, car audio systems, home theater systems, and home audio systems. Therefore, there is a present and future need for high performance, efficient, and reliable audio power amplifiers in a host of applications.

1.2Principles of sound and audio amplifiers

Unlike electromagnetic waves which propagate through free space, sound waves require a solid, liquid, or gas medium to propagate. Sound can be defined as a mechanical pressure wave moving in an elastic medium. Air is the most familiar medium but solids are better mediums for propagation of sound. The sources of sound can be categorized in six groups: (1) vibrating body (a vibrating vocal cord, a loudspeaker), (2) throttled air stream (a whistle), (3) thermal (a fine wire connected to an alternating current), (4) explosion (a firecracker), (5) arc (thunder) and (6) aeolian or vortex (a sound produced by wind when it passes over or through objects) [3].

Sound originates from a vibration source that displaces the medium particles in a backward and forward motion. This pattern is characterized with some generic properties such as wavelength, period, amplitude, and direction.

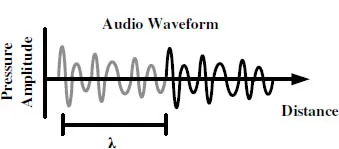

Fig. 1.2 Audio waveform across distance.

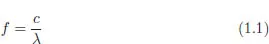

The wavelength of the audio waveform (λ) is the distance that the sound travels in a single direction along a medium in a repeating pattern between consecutive points of the same phase as observed in Fig. 1.2. The typical audio signal contains many different wavelengths with distinct amplitudes, but is typically represented by its Fourier transform as a sum of sinusoidal waves at different frequencies. The frequency of a signal, expressed in cycles per second, is expressed as,

where c is the velocity of sound in air at room temperature with value of 347.87 m/s. Other values of sound velocity in other medium are shown in Table 1.1.

Table 1.1 Velocity of sound in different medium.

| Medium | Velocity (m/s) |

| Rubber | 40-150 |

| Water | 1433 |

| Concrete | 3200-3600 |

| Bone | 3750 |

| Wood | 4176 |

| Glass, Pyrex | 5640 |

| Steel | 5790 |

Frequency of a sound wave can be defined only if the wave is periodic in time. The fundamental frequency of the audio waveform is the greatest common divisor of the frequency of all the different frequency components of the signal. The typical audio frequency spectrum that is perceptible by humans ranges from 20 Hz to 20 kHz, or wavelengths from 16.5 mm to 16.5 m. However, most of the signal power in human speech is in the frequency band from 200 Hz to 4 kHz. The frequency band of a telephone is normally bounded from 300 Hz to 3kHz. Only the labial sounds and the fricative sounds have frequencies as high as 8 kHz to 10 kHz; however, there is relatively little power at these frequencies [3].

The high end of the audio frequency spectrum (5 kHz up to 20 kHz) is rarely processed in audio tracks, and it is only used in high definition audio applications like orchestra music reproduction. The infrasonic band is the band below the lowest frequency that can be heard, and these sounds are typically felt and not heard since some of organs of the human body can exhibit resonance at these frequencies. On the other hand, the ultrasonic band is the band above the highest frequency in the audible band, and these frequencies are used in ultrasonic cleaners, traffic detection, ultrasonic imaging in medical applications, burglar alarm systems, and remote controls. It is interesting to note that the hearing range for dogs (64 Hz to 44 kHz) includes ultrasonic frequencies.

The audio power amplifier in a sound system must be able to supply the high peak currents required to drive the , which is usually a low impedance load in the 4–8 Ω range. An ideal audio power amplifier must have zero output impedance to provide all the available power from the supply; however, the practical audio amplifier has a non-zero output impedance that must be small when compared to the loudspeaker impedance [3]. To understand the tradeoffs involved in the design of audio amplifiers, it is useful to review their history, the loudspeaker basics, and the metrics used to qualify their performance.

1.3A brief history of audio amplifiers

Audio power amplifiers arose with the need of dealing with impulses which had to remain in a very definite time pattern to be useful. One of the earliest amplifying devices was the pipe organ. However, in a more generally accepted sense, amplifiers were invented when the nineteenth century technology became concerned with the transmission and reproduction of vibratory power: first sound, and then radio waves [4].

In 1876, Edison patented a device which he called the aerophone. It was a pneumatic amplifier in which the speaker’s voice controlled the instantaneous flow of compressed air by means of a sound-actuated valve. The air was released in vibratory bursts similar to those that came from the speaker’s mouth but more powerful and louder. Later on, an improved aerophone was attached to the phonograph [4].

The device which really opened up the field of amplification was the vacum tube or valve. Early developments of the vacuum tube were pushed by Lee De Forest in 1906 with the introduction of the audion [5, 6]. The audion was a three terminal device partially enclosed in a glass tube that allowed the movement of electrons between two terminals, filament and plate, controlled by a third terminal called the grid. A small signal applied to the grid could control a large amount of current from the filament to the plate, allowing the amplification of electrical signals. An early application of vacuum tube was to transmit and receive radio waves. Other applications followed quickly: recording and reproduction of sound, detection and measurement of light, sound, pressure, etc. Thus, in early 1920s until 1950s the audio amplifiers used vacuum tubes such as the triode.

After the invention and refineme...