- 252 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

From the Sun to the Stars

About this book

The book begins at the Sun then travels through the solar system to see the stars, how they work, and ultimately what they mean to us. The idea is to provide an integrated view of the galaxy and its contents. Along the way we look at spectra, atmospher

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access From the Sun to the Stars by James B Kaler in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Physical Sciences & Astronomy & Astrophysics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

Physical SciencesSubtopic

Astronomy & Astrophysics1

A Sunny Day

The Sun: A glowing ball of heat and light that everyone appreciates, especially when missing it on a cloudy day, and no one dares look at except perhaps when rising or setting in the horizon murk or when behind sufficiently thick clouds. It’s just too bright. But without its intense illumination, there would be no life, as nearly all the energy we live by ultimately comes from solar power, including that derived from fossil fuels. The seemingly simple solar facade hides a deeply buried nuclear engine that has allowed the Sun to glow at close to its current luminosity for nearly five billion years. And it has another five billion to go before it begins to die away, or perhaps better put, before it transforms itself into something quite different than it is today. That is a story for later, as is its place among its billions of siblings, seen at night as all the other stars sparkling against a blackened sky.

“Just the facts…”

Said Joe Friday. If that’s confusing, “You can look it up,” attributed to Casey Stengel or more likely James Thurber.

The Sun looks like a solid ball. It isn’t. Just the opposite, it’s gaseous throughout. It does not fly apart because it’s held together by its own inward-pulling gravity (Chapter 2), which compresses the Sun into a near-perfect sphere. The apparent razored edge is caused by highly opaque solar gases: you just can’t look very far into the apparent solar “surface” any more than you can into a fair-weather cloud.

Figure 1.1. Though 150 million kilometers (93 million miles) away, the Sun, our star, provides nearly all the energy we need to live and flourish. J. B. Kaler.

Everything about the Sun is huge, to the point that the numbers seem to take on lives of their own. The opaque surface of the Sun, the photosphere (from the Greek, meaning “sphere of light”), glows with a temperature of 5500 degrees Celsius (almost 10,000 degrees Fahrenheit), more than double that of the filament of a 100 watt incandescent light bulb.

In the Celsius system, water at sea level (so that it’s under standard atmospheric pressure) freezes at 0 degrees, boils at 100. Pull all the energy, all the heat, from a body and you hit rock bottom, absolute zero, at a temperature of −273°C (−459°F). At this level, all atomic and molecular motion ceases (at least in principle: nature can be contrary). The negative numbers of the two temperature scales are more than a bother. It’s far simpler to start the absolute Kelvin scale (after the Scottish physicist William Thomson, Lord Kelvin, 1824–1907) at absolute zero and work upward by degrees Celsius. Water then freezes at 273 K, boils at 373 K. You sit there reading at about 295 K. The solar surface temperature then becomes 5780 K. The range among even ordinary stars is spectacular, from a couple thousand Kelvin (back to the light bulb) to more than 50,000 K, with extremes to be explored that are far greater.

The Sun averages 149.6 million kilometers (93.0 million miles) away, with a 1.7 percent variation each way over the course of the year (which is not a cause of the seasons; we’ll get to that). That’s 400 times farther than the Moon, which averages 384,400 km (with a plus or minus 5.5 percent variation that influences the tides but is otherwise unnoticeable). The Sun is so far away that at freeway speeds it would take 150 years to drive there. The mean solar distance is a fundamental unit in astronomy that, not surprisingly, is called THE Astronomical Unit, or AU. The Sun as defined by the photosphere (and there is a lot outside it) appears just over half a degree across, by coincidence the same as the Moon, which makes spectacular solar eclipses possible. At the solar distance, that angle translates into a physical diameter of 1.39 million km (864,000 miles), about 1/100th of an AU, 109 times the diameter of Earth, four times the distance between the Earth and the Moon, which is as far as humans have ever traveled. Once you get to the Sun in your highly insulated car, it would take another decade to drive around it looking at the sights, which include bubbling gases, gigantic magnetic ropes and loops, immense explosions, and deep dark magnetic sinkholes with slippery slopes, many of which can dwarf the Earth. We are again in the middle of the range. Ordinary stars run from the size of our planet to nearly that of the orbit of Saturn, which has a radius of 9.5 AU. At the extreme, stars can be no bigger than a small town.

The numbers needed to describe the Sun and stars can be so large that we need a shorthand to write them out. Big numbers are usually expressed through exponents. As examples, 4 = 22 (2 × 2, two squared), 100 = 102. A number like 10,000 is 104, 50,000 then being 5 × 104. Using the shorthand, on a pretend Earthly scale the Sun weighs in at 2 × 1030 kilograms (2 followed by 30 zeros), or 2 × 1027 (two thousand trillion trillion) metric tons, 330,000 times that of Earth. The Sun radiates at a rate of 4 × 1026 (four hundred trillion trillion) watts. To run the Sun for one second, you would have to pay your power company the gross domestic product of the United States for a million years. Even at its great distance, an overhead Sun delivers energy at a rate of nearly 1400 watts per square meter of ground, shining to us here on Earth half a million times brighter than the nearby Moon. Sadly, we still do not have conversion methods good enough to cover a significant part of our earthly needs. Masses of other stars range from well over 100 times that of the Sun to a lower limit that approaches the masses of our large planets, while luminosities run from millions of Suns to bulbs so dim you could not see them were they in our own Solar System.

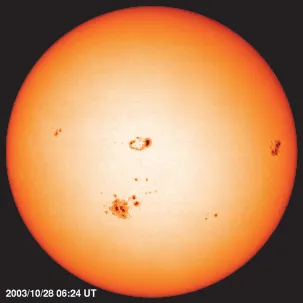

Figure 1.2. Highly opaque gases give the spherical Sun its sharp edge, or limb. The darkening and reddening toward the limb is the result of looking slightly more deeply, and thus to higher temperatures, at the center than near the edge. The much darker and cooler sunspots are regions of intense magnetic fields that impede the upward flow of hot gas from the interior. Solar and Heliospheric Observatory, NASA/ESA.

Big numbers aside, among the most remarkable properties is the Sun’s chemical composition. Very unlike Earth, and excluding the nuclear engine at the solar core, the Sun (similar to most stars) is made of 92 percent hydrogen and 8 percent helium (by numbers of atoms), which does not leave a lot of room for anything else. Within a tiny leftover bit of 0.15 percent we find all the other chemical elements, including the iron, silicon, and carbon of which the Earth is largely composed, making our planet actually quite special in spite of its small size. We are in fact a distillate of the solar gases with the light stuff missing. How do we know the solar composition? We can’t get there and sample it directly (though we can come surprisingly close to doing just that). To find out, we have to peel sunlight apart.

A Sun of many colors

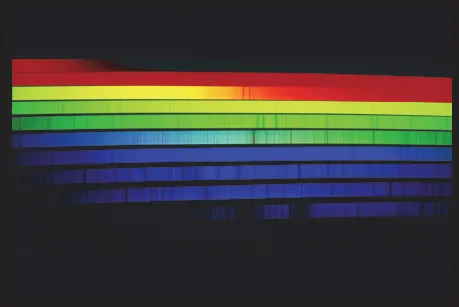

Sunlight looks to be a bit on the yellowish side of white. It actually shines with an amalgam of continuous colors from red through orange, yellow, green, blue, violet, and all the infinite shades in between, as demonstrated by Isaac Newton in the 17th century when he passed a narrow sunbeam through a refracting prism onto a cloth to reveal the solar spectrum. The eye then re-assembles the colors, merging them back into a visual near-pure white.

(Whatever happened to “indigo”? It’s there in the blue-violet. Unless we want to get into heliotrope and mauve, there are six basic colors. But seven is a magic number. There are seven moving bodies in the sky that represent major gods: the Sun, Moon, and the five planets known since ancient times, Mercury through Saturn. Honoring them, there are seven days to the week, each named after gods, the details depending on the language. We see the “Seven Sisters” cluster of stars in the sky, even though only six are readily visible. And so on. By early logic then, there must be seven colors, so we’ll make one up.)

At least in one view, light consists of a flow of electromagnetic energy that can be visualized as electric and magnetic waves moving at the “speed of light,” in vacuum at 299,792.5 kilometers (186,282 miles) per second. It’s the speed limit of the Universe; nothing can go faster. A light wave is described by its wavelength, the physical separation between the wave’s crests or troughs, or by its “frequency,” the number of waves that each second zip past a particular point. Multiply frequency by wavelength and you recover the speed (true of any wave, from water to sound). There are no known limits to the wavelengths in the electromagnetic spectrum. Light waves, optical waves if you like, those to which the eye is sensitive, have very short wavelengths that extend roughly from 0.000040 to about 0.000075 centimeter (2.54 centimeters to the inch), less than an octave. It’s more convenient to use a shorter unit, the Ångstrom, defined as a hundred millionth (10−8) of a centimeter (named after the Swedish physicist Anders Ångstrom, 1814–1874). The wavelengths of the visual colors then run from 4000 Å to near 8000 Å. Waves with the shortest wavelengths (below 4500 Å) appear as violet, those longer than 6000 Å as red. In the middle, orange centers near 6000 Å, yellow around 5500, green near 5200, blue 4800, until we get back to violet, the shades varying continuously with wavelength. When passing at an angle from air or vacuum into glass or water (or any other denser transparent substance), the waves slow and bend, or “refract,” toward the perpendicular, shorter violet waves more than longer red ones. Emerging, they speed up and bend again, now away from the perpendicular, which separates the colors even more: and we see Newton’s spectrum.

Figure 1.3. The visible solar spectrum, displayed in strips, runs from red to violet. The blend of color gives the Sun its slightly yellowish hue. The spectrum is crossed by hundreds of sharp dark lines. Each is produced by the absorption of sunlight by specific atoms, ions, or even molecules, in the semi-transparent outer solar layers. The pair just to the right of center in the third strip down is caused by neutral sodium, while the very broad pair in the bottom strip is made by ionized calcium. The dark line in strip six arises from ionized magnesium, while most of the rest are produced by iron and other neutral and ionized metals. In spite of appearances, hydrogen makes up some ninety percent of the solar gases, helium about 10 percent, which leaves little room for heavier atoms. National Solar Observatory, Sacramento Peak (New Mexico).

Up in the air

Whether aware or not, everyone is familiar with the solar spectrum, as it plays out in a great variety of attractive ways, most notably in the rainbow. An afternoon thunderstorm blows off to the east, allowing sunlight to fall upon its raindrops, each of which acts as a small Newtonian prism. Single one out. As a sunbeam enters the droplet, it bends and splits into its component colors, red through violet. Reflecting from the drop’s backside, the spread beam exits and widens yet more, the reversal in direction sending the split ray back into your eye. The combination of all drops combined with the refractive properties of water creates a circular colored ring 42 degrees in radius around the point below the horizon opposite the Sun. Since its waves refract the least, red will be on the rainbow’s outside, blue or violet (because they refract more) on the inside. Sunbeams that hit the droplets just right can reflect twice off the backside, which produces a second, larger bow outside the bright one of 51° radius, the double reflection also reversing the colors. If the inner bow is at all bright, the outer one will always be there. Sometimes you’ll see a series of pink “supernumerary” bows inside the main one that are caused by light waves interfering with one another; if two waves fall wave-to-wave, they add together, while if they fall wave-to-trough, they cancel, giving us a bright-dark-bright-etc. pattern. If the Sun is too high, more than halfway up the sky, the point opposite the Sun will be below the horizon and the main rainbow cannot be seen against the sky. Rainbows thus appear in the early morning or late afternoon when the Sun is low enough to loft the bow into visibility.

Separation of solar colors is a natural part of the day. “Why is the sky blue?” asks the curious child. An alternative view of light is that it’s made of speeding massless particles, or photons. The modern concept in the weird world of quantum mechanics (which considers the realm of the very small) is that light is both a wave and a particle at the same time. Its behavior depends on how you observe it. You might think of a photon as a chunk of a wave, though that’s not a very accurate description; nor is any other. Some of the incoming solar photons bounce off air molecules (made mostly of nitrogen and oxygen), which changes the photons’ directions. The process is far more efficient at shorter wavelengths that are closer to the molecules’ sizes. Violet photons (they are not colored, that is just the effect they have on the eye) are fiercely scattered, whereas longer red photons are not affected much at all. Blue and violet solar photons then get knocked all over the sky, resulting in some coming into your eye from any direction. But there are relatively few violet photons in sunlight, nor is the eye very sensitive to them, so most of the scattered photons we see are blue. Hence the glorious azure sky, which varies in its shade according to the angle above the horizon and angle to the Sun. But it’s all still sunlight. The blue sky is so bright that the stars disappear behind its veil. Only Venus glimmers through it.

If you pull blue and violet photons out of sunlight, the Sun itself must appear to be colored more toward the longer wave end of the spectrum. The complement to a blue sky is then a somewhat yellowed Sun that turns golden as it approaches setting, and at the extreme turns reddish. The sky looks as if it is a dome over your head. It isn’t. The air is actually a thin layer that hugs the ground and fits to the curvature of the Earth, the density and pressure dropping off quickly with height, as anyone who climbs mountains will happily tell you. Toward overhead, you see outside to space through the thinnest part of the layer. As your gaze drops downward, you have to look through more and more air. A third of the way up from the horizon, you see through double the overhead thickness, while at the horizon itself you look through 38 times more air than when you look directly above you. As a result, the light of the setting Sun has a longer pathway over which it is scattered, and with more blue light removed, the Sun turns both dimmer and redder. The effect is enhanced by the absorption and scattering of solar photons not just by the air, but also by watery haze and pollution, both natural (from volcanos) and artificial. Light clouds near the horizon will reflect the reddened sunlight, giving us wonderful orange and red sunsets. The effect increases during early twilight after the Sun falls below the horizon but can still illuminate the upper atmosphere, for a brief time (until the intervening Earth gets in the way) giving sunbeam even more air to contend with.

Just as liquid water refracts and disperses the colors, so does ice. Ice crystallizes into six-sided hexagons (remember the snowflake on your mitten?) that form tiny prisms. Put thin icy clouds in front of the Sun, and they can create a colored ring 22 degrees (the bending angle through the sides of the hexagon) in radius with the Sun in the middle. Because the bending angle increases with decreasing wavelength, the “22-degree halo” is red on the inside and blue on the outside. (Be sure to hide the Sun behind something so as not to look at it directly.) As the Sun sets, spots on the ring on a line through the Sun parallel to the ground grow in intensity until these sundogs (mock suns, or parhelia) dominate. A white ring parallel to the ground caused by icy reflection may in rare instances extend through the sundogs and encircle the entire sky. Refraction through the square sides of the icy prisms produces a rare ring 47 degrees in radius. Various arcs tangential to the rings might paint the blue canvas as well. Most are related to the 22-degree ring, though one, the “circumhorizontal arc,” which is attached to the lower edge of the 47-degree ring, can be bright and beautiful even when the ring itself is not there, leaving a sort of rainbow floating in the sky beneath the Sun. And if you live in the wintery north and don’t want to wait for a solar halo to see refracted solar colors, just look at the sparkles of sunlight off crystals of new snow.

Great fun can be had by looking out an airplane window. Here we might see especially intense sundogs, as well as the pure reflection of the Sun off light icy clouds below the craft, making a white “subsun” that follows along with you, the clouds sometimes so transparent as to be practically invisible. They’ve been taken for UFOs (see Chapter 8). If you are positioned right, you might see the shadow of the plane cast on the clouds below. Interfering light waves combined with reflection may produce a colorful halo, the “glory” (sometimes called the pilot’s rainbow), around it. At best, multiple colored rings grace the cloud deck, and if the clouds are far away, the airplane’s shadow becomes lost, leaving nested colored rings floating in the air.

Clear air not only scatters, but as a “substance” (albeit a light one), it must also refract. As sunlight enters the layer of air above us, it bends downward, toward the perpendicular. All celestial objects as viewed fro...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Halftitle

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- What It’s All About

- Chapter 1 A Sunny Day

- Chapter 2 The Wanderers

- Chapter 3 Seeing Far

- Chapter 4 A Celestial Tour

- Chapter 5 Out of Darkness

- Chapter 6 An Infinite Variety

- Chapter 7 Star Lives

- Chapter 8 Other Worlds

- Index