- 580 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Nobel Prizes and Notable Discoveries

About this book

-->

This is the third book in a series presenting Nobel Prizes in the life sciences using the remarkably rich archives of nominations and reviews which are kept secret for 50 years after the awards have been made. The two previous boo

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Nobel Prizes and Notable Discoveries by Erling Norrby in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Biochemistry. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

BILLIONS OF NERVE CELLS

UNCOUNTABLE NETWORK CONTACTS

OUR BRAIN, A WONDER

UNCOUNTABLE NETWORK CONTACTS

OUR BRAIN, A WONDER

Once in the dawn of modern big time there was a human primate ancestor living in the heart of Africa who looked at his face in a pond. He reflected on the fact that what he saw must be his own image. He further pondered on this particular moment of his existence. His thinking led him to deduce that this existence extended from the time when he was born to the present fleeting moment. It also extended into a future time of unpredictable length. As his thoughts meandered further they came to focus on the — irrelevant? — question, if his existence as an individual could possibly have a meaning. Thus was born the human primate consciousness about consciousness.

Of course in reality, emergence of consciousness was an incremental process. Throughout eons of evolution there has been a progress from perceived awareness of ever increasing complexity towards the advanced form of (self-)consciousness enriching the life of us humans. The uniqueness of human consciousness is the emphasis on the subject, the capacity to reflect, to plan and to act. Not surprisingly attempts to understand consciousness has challenged the most brilliant inquisitive minds of humans. Naturally it is tantalizing to think about and examine the organ with which we think — to be aware of the existence of possibilities for self-reflection. There is, however, often a pronounced difference between how natural scientists and philosophers/humanists conceptualize this state and which qualities of mind they emphasize.

Before approaching the epitome of integration of nerve functions, consciousness, it was imperative to understand the basic functions of the nervous system. This included interpreting its anatomy. The function of individual specialized cellular components needed to be elucidated. The critical cell, the neuron, with its particular extensions, was identified. These extensions were found to be of variable length and to carry different functions. The shorter extensions, the dendrites, generally, communicate electrical signals from the periphery to the cell body. These signals are then processed and transmitted in an integrated form from this body to the periphery by axons. The axons form bundles which are referred to as nerves. The nerves may stretch over long distances, in the human body maximally from the spinal cord to our big toe.

The nervous system has two major parts, the central and the peripheral structures. The central part includes the brain and the spinal cord. The brain can be subdivided into the large brain, cerebrum, and the small brain, cerebellum, which are connected via their underlying structures, the brain stem, and the spinal cord. The stem includes several distinguishable parts. These will be presented in more detail below. Throughout evolution it is the central nervous system that has shown the most dramatic development in multicellular organisms. In general there is proportionality between body size and brain size, but in primates the brain is relatively larger compared to other vertebrates (elephants and whales have the heaviest brains of any animal). In primates it is in particular the convoluted cortex, looking like a cauliflower which added to the weight. Over about three million years the hominin brain has increased in volume some three times to its present size in modern humans. It might be noted that Neanderthals, who became extinct some 30,000 years ago and with whom we had joint offspring, had somewhat larger brains than the modern Homo sapiens.

The right half of the primate large brain is generally larger than the left. Furthermore individual parts of the brain can increase in size after prolonged and intense training. The brain size of men on average is about ten percent larger than the brains of women. However, it should be emphasized that it is not the size of the brain that decides its fully developed capacity to integrate information. The critical factor in the brain is the propensity for development of synaptic contacts and these in turn are consequential to exposure to appropriate environmental stimuli. There are many stages in the development of the embryonic brain to that of the full grown individual. New networks of connections are continually established and trimmed. Cells are retained or removed by programmed cell death, during some periods of the young life at an impressive speed. The flexibility in functions of the brain is remarkable. It is per weight the most energy-consuming organ in the body. That is the reason for the fact that about 20% of all circulation of blood passes through the brain, which weighs only 1.3 to 1.4 kilos in adults. Since it needs to be quick in action it gains calories from using the rapidly metabolized carbohydrates, mostly glucose converted into lactate, in the blood. The mobilization of regionalized brain activity can be readily detected by measuring the local blood flow using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to be discussed further in Chapter 3.

The peripheral part of the nervous system is represented by pair-wise nerves. Twelve cranial nerves communicate with the brain structures directly or via their relay stations, except the first two pairs, including the olfactory nerves, which end up directly within the brain stem. In all vertebrates there are efferent nerve fibers which transport electrical signals from a central organ like the spinal cord to for example a muscle allowing the initiation of a controlled contraction of this structure. However, nerves generally represent a two-way form of communication allowing sense organs in muscles to inform central structures about the conditions of tension of the tissues. The latter kind of nerve fibers is called afferent. There are many kinds of afferent fibers, which transport signals from the different sense organs — registering pain, touch, taste, light, sound, etc. — to the spinal cord and possibly further to higher centers in the brain or directly to the latter organ. Whereas efferent nerves act directly on their target cells, like muscle cells, the afferent sensory nerves pass via a collection of cell bodies outside the scull — a structure referred to as ganglion — which serves as a relay station. The central nervous organs are highly complex integrating centers which orchestrate input and output signals. The intricate nature of this system increases with the life form and in vertebrates the highest complexity of the brain is found in humans. Thus a roundworm, Caenorhabditis elegans, a popular experimental animal introduced by Sydney Brenner (recipient of the shared 2002 Nobel Prize in physiology or medicine1) has 302 nerve cells which form about 7,500 contacts, whereas humans have about 85 billion nerve cells which establish of the order of 1014 to 1015 contacts. Incoming signals may elicit a wide range of reactions, like activation of different categories of muscles in a flight reaction. The prime functions of centers at different levels with the most advanced integrating functions located to the brain cortex are to allow the animal to manage its environment, to survive. To secure the capacity to reproduce is equally important.

Attempts to decipher the function(s) of the brain, from its simplest to its most advanced forms have been the focus of many studies of animals and man. Neurobiological research has provided deep insights into the operations of the nervous system, not least due to the development of remarkably refined techniques for measurements of the electrical nerve activities. This development has been dependent on the introduction of new physical methods for examination of weak currents, and later for examination of the genetics and chemical dynamics of the functions of the brain by use of molecular techniques. However, studies of the brain started way before the present time. In fact it does not suffice to go back to the ancient Greeks.

The first mention of the brain is in a text using hieroglyphs. It was an Egyptian battle surgeon who in the 17th century BCE noticed that damage to one side of the brain led to symptoms also from one side, a phenomenon referred to as lateralization. Lack of speech after damage and seizures were also mentioned in this remarkable text. More than a thousand years later the Greeks dominated speculations about the function of the brain. However, because they considered the human body sacred they generally did not perform dissections. Although some thought that the brain was a center for registration of sensations and for intelligence, Aristotle’s school favored another view. It located intelligence in the heart and saw the brain as a cooling device. And of course we still learn things by heart today. The situation changed in the first half of the third century BCE. Herophilus and Erasistratus in Alexandria made dissections of the dead and even vivisections on prisoners. The anatomy of the brain began to be revealed. A distinction was made between the large brain and the underlying small brain. Furthermore the presence of liquid-filled spaces, the ventricles, was also recorded. Nerves were shown to be distinct from ligaments and tendons and functionally they were separated into motor and sensory nerves. Nerves of the former kind transmitted signals to the muscles a concept consolidated some five hundred years later by Galen’s vivisection experiments on animals.

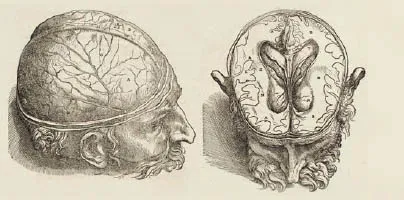

Progressively the anatomy of the brain was revealed and in the 16th century it became known in its main structures by the remarkable atlases developed by Andreas Vesalius. Two hundred years later the physicist, natural scientist and physician Luigi Galvani stumbled on the discovery that electricity played a central role in the contraction of the leg of a dead frog. His serendipitous finding was made by use of the following experimental setup. A dissected frog was suspended in a copper wire attached to an iron tripod. As the muscles of the frog relaxed the leg it came to touch the iron foothold of the tripod. The muscle then contracted and became disconnected from the foothold. Repeated contractions could be registered by this experimental arrangement and we can now interpret this to be due to the fact that a current could flow when the foot contacted the tripod. Galvani interpreted the observed phenomenon differently. He believed that electricity was generated in the body of the animal. Many scientists became interested in the effect of electricity on the body and speculated on the possibility that it could be used to heal certain disease conditions. Among those can be mentioned the natural scientist and statesman Benjamin Franklin and the co discoverer of oxygen Joseph Priestley. Carl Linnaeus also became fascinated by what he called spiritus animalis and another famous Swede, who we will meet in Chapter 4, Jacob Berzelius, wrote his thesis reflecting on the therapeutic use of electricity in the treatment of different diseases.

The human brain as illustrated by A. Vesalius. [Courtesy of the Hagströmer Library, Karolinska Institute.]

Thus electricity could play some kind of role in biological systems, including in the brain. Other important speculations on the latter organ were made by Descartes in the same century. He proposed the theory of dualism possibly to conform to the theocratic conditions of his time. Dualism implied that functions of the body and the mind were organically separated in the brain. He even suggested that a possible site for the mind was the pineal gland, a small cone-like structure at the bottom of this organ. Only humans had a soul and animals were automata, controlled by reflexes only. The Cartesian dilemma has haunted scientists way into the mid-twentieth century and we will return to this in the next chapter.

Phrenology, a term derived from Greek words meaning knowledge of the mind, was a pseudoscience at the turn of the 19th century and it was highly popular for some 50 years. The idea was that character, thoughts and emotions could be mapped to different distinct regions of the brain. During the early part of the twentieth century the Italian physician Cesare Lombroso reintroduced the concept for use in investigations of evolution, anthropology and criminality. Personal traits were considered to be reflected in the detailed structure of the skull. In the spirit of the time it was argued that Europeans were superior to other lesser races. The use of slavery was encouraged. The movement slowly died out when more serious studies were made of the effects of localized damage to the brain, mechanical or because of a bleeding or of blood clotting, thrombosis. In pioneering studies the French physician and anatomist Paul Broca identified a location in the frontal lobe, that, when damaged, led to the loss of capacity to form articulated language, expressive aphasia, from Greek for speechlessness. The site is now referred to as Broca’s area. Similarly, the German physician and neuroanatomist Karl Wernicke wanted to examine the effect of certain brain lesions on speech and language. He observed that not all deficits of language could be explained by damage to Broca’s area. There were other situations when the critical region was located further back in the brain, in a structure referred to as left posterior, superior, temporal gyrus. Damage to this region, Wernicke’s area, led to receptive aphasia. In extended studies there has been an expanded mapping of the allocations of many different functions to the different regions of the brain. In right-handed people Broca’s and Wernicke’s areas are found almost exclusively on the left hemisphere, exemplifying the phenomenon lateralization introduced above.

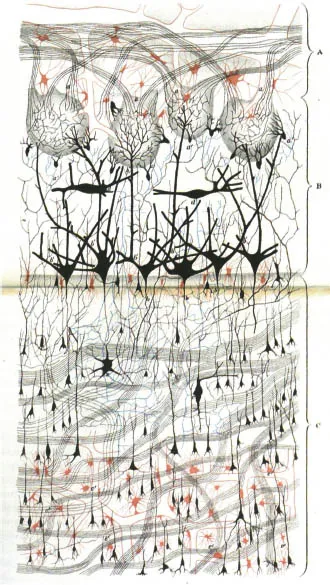

There were a number of important steps in the growing insight into the networks formed by nerves in the brain. One of the pioneers in this growing field was the Czech anatomist Jan E. Purkyně. Originally most of his work concerned our senses in particular vision but he was also interested in our sense of balance. His studies on vision focused on how we interpret colors and in this context he befriended Goethe, the father of his own farbenlehre. Beginning in the early 1830s Purkyně started to use an achromatic microscope to examine the brain. Large cellular structures could be identified, and the exceptionally large cells in the cerebellum are still today called the Purkinje cells. Progressively histological techniques were improved. The texture of the soft tissues could be fixed, thin sections could be prepared and most importantly effective stains for different purposes were developed. The detailed anatomy of nervous tissue could be revealed by use of a staining technique employing silver chromate introduced by the Italian scientist Camillo Golgi. His staining technique was developed further and systematically employed by the Spanish scientist Santiago Ramon y Cajal. These two scientists shared the 1906 Nobel Prize in physiology and medicine. We will soon meet them again.

The discovery that a unique kind of cell in the brain, the neuron, was the central actor in the transmission of signals, for example between the brain and muscles, revolutionized the field. The term neuron for the nerve cell was introduced by the German late nineteenth century anatomist Heinrich W. G. von Waldeyer-Hartz in an excellent synthesis of the pioneering discoveries by Golgi, Cajal and others. He postulated that neurons had a central role in the function of nerve tissues and that they had the particular quality of being electrically excitable. His proposal was referred to as the neuron doctrine. The word neuron has a Greek origin and was used to depict a string. It was used for the first time in Homer’s Iliad. On the side it can be mentioned that Waldeyer-Hartz also coined the word chromosome, for the structures carrying the genetic material. The network of fibers connecting cells in the brain fascinated scientists from the first moment of its discovery and into the present time. An example taken from the olfactory epithelium of a dog illustrates the intricate networks of nerve cells and fibers, as a reminder seen only in two dimensions.

The networks of nerve cells and fibers in the olfactory epithelium of a dog. [Courtesy of the Hagströmer Library, Karol...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Halftitle

- Title

- Copyright

- Preface

- Contents

- Chapter 1 Neurophysiology, a Discipline Developing Consciousness

- Chapter 2 Testing of Nobel Prize Patience and a Near Prize Recipient

- Chapter 3 Two British Neurophysiologists and the Potential for Action

- Chapter 4 Advances in Organic Chemistry and Two 1955 Nobel Prizes

- Chapter 5 A Tale of Two Gentle Scientists Who Changed the World

- Chapter 6 1964 — An Important Year in the World and for Nobel Prizes

- Chapter 7 Magnifiques, Nos 3 Nobel (Our Great 3 Nobels)

- Chapter 8 A Scientist of Many Talents

- Chapter 9 From Heroic War Efforts to Intellectual Battles

- References

- Index