![]()

Part I

Introduction, History,

and Overview

![]()

Introduction to the Brain and Nervous System

“And this I believe: that the free, exploring mind of the individual human is the most valuable thing in the world. And this I would fight for: the freedom of the mind to take any direction it wishes, undirected. And this I must fight against: any idea, religion, or government which limits or destroys the individual.”

— East of Eden by John Steinbeck, Nobel Laureate

(Literature, 1962)

The human brain is the most impressive structure Mother Nature has created. In fact, it is the most complex structure in the observable universe. It is capable of producing emotion, malleable enough to dynamically modify itself, and more powerful than any computer ever created. Despite these amazing feats, it consumes only 20 watts of energy (similar to a light bulb), is extraordinarily compact, and has mystified the greatest scientists in the history of humanity.

Life is interesting in that we are constantly exposed to dynamic sensory experiences — yet we rarely are aware of it. The brain is an organ that is able to recognize its own existence, which in itself is incredible. The fact that we are able to be consciously aware of ourselves, interact with other human beings in an incredibly complicated social landscape, produce machines and devices that are capable of artificial intelligence, and explore other planets is but a small homage to the brain’s incredible capacity.

The brain is the seat of emotion and personality. It bestows us with individuality, our ability to empathize, contemplate the future, and recollect the past. When it is properly functioning, it truly is a miraculous system that is more capable than the world’s largest and most powerful supercomputers.

The beauty of nature and the complexity of the world can be appreciated and comprehended by the brain. The sights and sounds of a bustling city are perceived by the very organ that created them, and we were somehow able to figure out how to leave the very planet from which the human brain evolved in order to explore our role in the universe. Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony and the Mona Lisa were beautiful masterpieces of the brain. The human brain is continuously integrating and synthesizing data from the external environment, and producing a continuously seamless experience of consciousness. This results in a beautiful symphony of emotions, ideas, experiences, and beliefs that diversify and color the world around us. These feats are extraordinary to say the least, and they were all accomplished by an incredible population of humans thanks to the mass of cells within their skulls.

The human brain has the consistency of soft tofu, and despite the brain being so prolific, everything could be lost in the blink of an eye. During one of our many experiences working in the Neurosurgery Department at the University of California Irvine Medical Center, the team we were working with was called in to evaluate a trauma case that had just rolled into the emergency department (ED). The individual whom we saw was breathing lightly, was still wearing his regular clothes, and looked otherwise normal. The only abnormal thing about him was the fact that there was a massive hole in his skull from a self-inflicted gunshot wound. On the side where the bullet exited the skull was a hole with grayish material protruding from it — this was fresh brain matter that had left his skull due to the momentum of the bullet and the subsequent swelling within the cranial cavity. We threw some gloves on and one of the emergency room doctors asked us to try and clean up the brain matter and debris that was protruding from the bullet wound. As we did so, we were thinking just how soft and delicate the brain really is — and were reminded of just how incredible it is. Yet unfortunately, many people take its miraculous capabilities for granted. The patient that we were working on was eventually placed on artificial respiration since he was an organ donor, and after his organs were harvested the following day, he unfortunately died. He was in a vegetative state due to the massive amount of damage to his brain, and despite the fact that he had a perfectly functioning body, his mind was destroyed by the bullet’s path, and the very organ that makes a human being was destroyed. Although in Alzheimer’s disease the brain is not destroyed in the blink of an eye, the process is equally disruptive. The brain is what makes us who we are. As we continue to explore the brain, we are better able to understand how it works, and how it malfunctions in the case of Alzheimer’s disease. However, prior to discussing Alzheimer’s disease in detail, we will start with an overview of the human brain and the components that make it up.

Human Brain: Structure

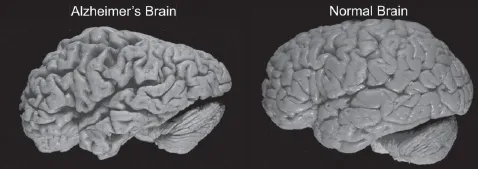

The average human brain is 3 pounds (1,300–1,400 grams, about the weight of a bag of sugar or flour), or 2% of total body weight (Fig. 1.1). One study found that with increasing age, brain weight decreases by 2.7 grams in males and 2.2 grams in females per year.1 Despite the brain making up such a small fraction of the total body weight, it is tremendously thirsty for nutrients, and 15% of the blood pumped by the heart (total cardiac output) goes to the brain. Additionally, the brain consumes 20% of the body’s oxygen and 15% of total body glucose (sugar) due to its high metabolic demand.2 The average human brain contains 100,000,000,000 (100 billion) brain cells (neurons), which is equivalent to the annual economic impact in dollars of Alzheimer’s disease in the United States. Additionally, for each neuron, there are approximately 10 supporting cells (glial cells) — meaning that the average human brain has 1,000,000,000,000 (1 trillion) cells. What is even more astounding is the fact that each neuron makes hundreds and sometimes thousands of connections to other neurons in the brain, resulting in an incredible amount of complexity and refinement that is unparalleled by anything else in the universe.

Fig. 1.1. A normal brain (right) compared to a brain with Alzheimer’s disease (left).3 Note the drastic changes in size and shrinkage due to loss of brain cells in the Alzheimer’s brain.

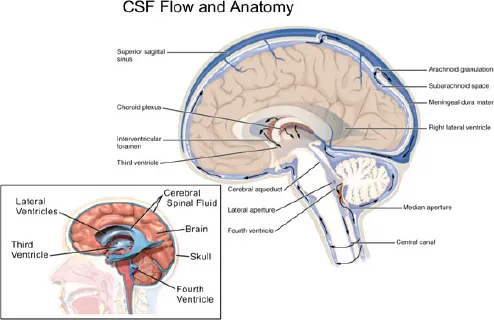

In order to function optimally, the brain has a built-in “filtration” system that removes toxic waste products and nourishes the brain. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) is a clear fluid found in the central nervous system (CNS), which includes the brain and spinal cord. The CSF is produced from the frond-like choroid plexus that resides within the cavities of the brain (Fig. 1.2). These cavities are called ventricles. CSF is also produced by the cells that make up the linings of the ventricles (known as the ependymal cells). After CSF is produced, it flows downwards through the brain from the lateral ventricles where it is formed, then to the third ventricle and through the aqueduct of Sylvius, and finally through the fourth ventricle at the bottom of the brain. As the CSF flows, it moves through what is known as the “subarachnoid space.” This is a space that is found immediately above the brain and spinal cord, and is called “subarachnoid” because it is a space beneath — or “sub” — a protective layer of the brain known as the arachnoid. From the fourth ventricle, the CSF covers and nourishes the spinal cord, then flows over the surface of the brain, where it is reabsorbed back into the bloodstream. The reabsorption occurs thanks to what are known as “arachnoid granulations.” These granulations protrude from the arachnoid that covers the brain and help reabsorb CSF that has already flowed through the CNS. While the primary function of CSF is to cushion the brain within the skull and function as a shock absorber for the CNS, CSF also circulates essential nutrients that are filtered from the bloodstream and aids in the removal of toxins from the brain.

Fig. 1.2. Cerebrospinal fluid, or CSF, is produced by the choroid plexus and ependymal cells of the lateral ventricles → third ventricle → fourth ventricle → subarachnoid space over the brain and spinal cord → arachnoid granulations → reabsorption in venous blood. (Modified from Refs. 5 and 6.)

CSF is produced at a constant rate of 0.3 mL/min. This rate is equivalent to one drop of water dripping from an empty faucet every 3 seconds.4 Interestingly, this rate of CSF production actually decreases in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Although the cause of this decrease is not entirely known, it may play a contributory role in the damaging effects of the disease. As CSF is produced, circulated, and reabsorbed within the brain, it helps nourish the cells within the brain, clear and filter out toxins (including the abnormal proteins found in Alzheimer’s disease), and maintain the optimal environment for the proper functioning of brain cells.

During this cycle, CSF removes toxins from the brain. It does so by the one-way flow of CSF towards the bloodstream, where it is eventually reabsorbed and removed from the brain. In addition to removing toxins and waste products from the brain, the CSF transports hormones from the body to specific parts of the brain. Additionally, CSF provides an interface between the brain and the rest of the body, and serves as an important regulator of normality and homeostasis within the brain.

Since the year 2000, many published studies have found an important physiological link between CSF and the fluid surrounding the brain cells, known as the cerebral interstitial fluid. This link has prompted increased focus on a better understanding of the role of CSF ...