![]()

CHAPTER 1

INTRODUCTION

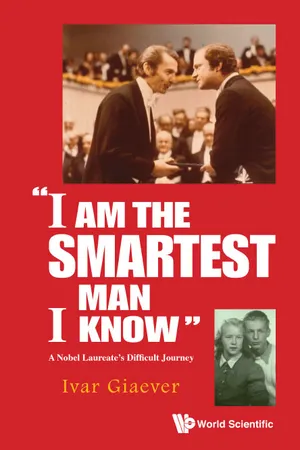

Life is not fair, and I, for one, am happy about that. That I should receive the Nobel Prize in Physics coming from a tiny village in Norway was very unlikely, and I shall try to describe in this small book, how and perhaps why it happened to me. I do not write a diary and thus must rely on my memory, so the story may be somewhat choppy and not exactly correct, but I promise to do my best. I should say here that I have a brother, John, who is only about a year older than me; we grew up together and we shared most of our memories for the first 16 years or so. But I left for Canada when I was 25 years old, while he stayed in Norway. Sometimes now when we get together to swap stories from our youth, I am very surprised how bad my brother’s memory is! So keep that in mind as we go along.

When I think of how things worked out for me, I am amazed at how life depends on a myriad of small things and tiny decisions. For example, if you had left only one second later, you would not have had the accident; if you had not stopped to have ice cream, you would never have met your wife; if your grandfather’s first wife had not died, your father would not have been born, and so on. Luck is very important in your life, but I am not the only Norwegian with luck. Mette-Marit is now a Norwegian princess destined to be the Queen of Norway. Before she married the Crown Prince, she had several affairs and a child out of wedlock with a man arrested for drugs. This is not a normal past for a future queen! Life is really chaotic and probably completely random, but most people will not accept that and therefore, perhaps by way of explanation, religion has come into play. In an attempt to come to terms with life’s unpredictability, people often think, “It must be God’s will, or God’s ways are mysterious, but He has a hidden purpose.” To those people I say that hopefully one of God’s purposes was for us not to enjoy all the religious wars that have happened throughout history. As I understand world religion, the Jews, the Muslims, and the Christians all pray to the same God, and thus they put Him in a difficult position, because which religion should He favor? I am not religious today even though when I was a child my mother told me that when it rained, it was because the angels in heaven were crying. And hanging over my bed there were color pictures of baby angels or cherubs with feathers and wings. Perhaps at the time those pictures were made, artists thought that angels were some type of bird? Yet even today, a real Norwegian-born princess claims she can communicate with angels, talks about their feathers, and has turned her beliefs into a profitable business. She has actually established a private school where people who apply and are admitted are promised to come into contact with their own guardian angel. So lots of strange things still go on with religion in Norway. But in this, Norway is probably a lot like every other place. It is unfathomable to me that people actually continue to kill each other in 2016 because of different religious beliefs. And if you have a military uniform on, you are licensed by your government to kill!

When I was a child, every night I was told to say a simple prayer which sounded something like this: “Dear Jesus Christ, thank you for a nice day; good night mama and papa, in Jesus’s name, Amen.” But despite my bedroom angels and bedtime prayers, I was fortunately not raised in a strictly religious home; neither my mother nor my father was really religious, and therefore I was not indoctrinated. I believe, as Richard Dawkins, that children are not born Jews, Christians, or Muslims, and perhaps the best thing we can do as parents is to avoid the temptation to make them one or the other. When you get really old, sometimes you want to hedge your bets about religion, and this happened to my mother when she was in her nineties. She asked me a few times about the afterlife. I tried to gently reassure her that she did not have to worry because if there really was an afterlife, she had been good and would certainly qualify for heaven. I am now 86 years old, almost as old as my mother was when she started asking me questions about the afterlife. Unlike my mother, I am at peace with life’s randomness. I take responsibility for my own actions, even though — or maybe because — I have had more than my share of luck.

![]()

CHAPTER 2

GROWING UP IN NORWAY

Like almost everybody on Earth I had two parents who never went to college or even high school. But they were good and intelligent people. My father was a pharmacist. In order to become a pharmacist at that time in Norway, one had to spend a semester at university after 10 years in public schools. My mother had the same education as my father, except she never went to university. Besides helping out at the drugstore a few times when they were short of workers, my mother was home taking care of her family. At the time that was what most women did. Both my parents were interested in reading, and we had a lot of books. Books then were expensive and I can remember that my father bought books from auctions in Copenhagen, Denmark. I do not think he shopped at auctions to save money. Instead, he truly liked the surprise and suspense of receiving and opening the big wooden crates. He always hoped to find a nugget or two inside the crates, but the contents were mostly cheap literature in Danish. It was okay that the books were written in Danish because at the time there was little difference between written Danish and Norwegian. That was due to the fact that Norway had been under Danish rule for 400 years, until 1814. Norway then entered into a union with Sweden. It was about this time that the average Norwegian became literate. Since we had been ruled by Denmark for such a long time, the official written language remained Danish. I actually learned to read the year I had my tonsils removed. I must have had lots of colds when I was young, or the decision to remove my tonsils would not have been made. It was a medical fad at the time, because tonsillectomies are seldom performed today. Today we seem to trust nature a bit more; if you were born with tonsils, maybe they do something important that we haven’t figured out yet. At the time we lived in a little village called Lena, but the operation was done is a city called Hamar where they had a hospital. The city was a two-hour boat ride across Mjøsa, the name of the biggest lake in Norway. I was only about 5 years old, and I clearly remember lying on the operating table. The surgeon asked me to count backwards starting at 100. By the time I got to 94 I was out cold. When I woke up, my head was on a rubber pillow and blood was coming out of my mouth. The surgeon and my mother were there, and I cried like a stuck pig. The doctor said, “If you don’t stop crying, your mother must leave.” So of course I cried even more, and my mother left. The next thing I remember is waking up in a room in the hospital with 4 or 5 adults. I guess there was no children’s ward in the hospital at that time. My mother had left me with several children’s books. Since I was the only child in that ward, I must have become everyone’s little pet; I remember all the adult patients were eager to help me. One book had simple sentences with words missing. You could guess what the words were by gluing the correct pictures into the blanks. After a short time I suddenly recognized I could guess where the pictures in the books should go by myself, and after that I could sort of read.

Ivar as a baby, 1929

Some of the first books I ever read were Edgar Rice Burroughs’s Tarzan stories in Danish which, for a child about 5–6 years old, was very exciting reading. I just skipped over the complicated names of the apes and other jungle animals, never trying to pronounce them. I simply associated the collection of letters with the characters in the book and didn’t get bogged down in name details. Interestingly, to this day I do the same thing, even if the hero has a simple name like John and the heroine is Jane. I can never recall the names when I have finished a book. In Feynman’s memoir, if I remember correctly, he wrote about his father who did not tell him the names of birds and animals but just how they acted and behaved and why they did so. So maybe I have a knack for that thanks to the Tarzan books.

Right after I learned to read, my grandfather told me that a great man is born only every 100 years, which made an impression on me. We had a small encyclopedia at home, and so with my grandfather’s words in mind, I started to go through it systematically from the beginning, looking for someone great born on April 5, 1829, exactly a hundred years before my birthday. I took my grandfather’s word literally as children are apt to do. I could not find anybody, so I decided that I was not to become a great man. But I can’t remember if I was disappointed by that new discovery! My grandfather also had a Bible with only illustrations, and the pictures of Noah and his Ark, along with the images of the desperate, almost naked people on top of high mountains facing sure death as the water was rising, fascinated me. Another memory from that picture Bible is Joseph lying at the bottom of the snake pit where his brothers had thrown him. He was apparently unharmed, but horrifically surrounded by vicious-looking snakes and scorpions and his brothers were to blame. This made an impression on me because I had never been able to get along very well with my brother either. He was a year older than me, but I was bigger and stronger than him. So that could not have been easy for him. When we fought, which was rather often, I usually won if it was a fair fight. I actually own that Bible today, but my kids never looked at it because I did not have it when they were small.

Another thing that intrigued me was my father’s globe. Much of Africa was colored white. My father told me that the white sections represented undiscovered territory. And he told me the story about Stanley and Livingstone. Stanley went looking for Livingstone in Africa. When he discovered a white man in some place, he reached out his hand and said that famous line: “Dr. Livingstone, I presume?” I thought maybe just like Stanley and Livingstone I could go to some faraway place like Africa when I grew up and discover wonderful, magical things. Or, I could be like Roald Amundsen and Fridtjof Nansen who were great heroes in Norway because of their polar expeditions. Growing up, we were constantly reminded of Roald Amundsen’s victory over Robert Scott when they had a “race” to the South Pole. We had been told that Scott used tractors that broke down in the cold, while Amundsen used sled dogs. And that they also ate their dogs in a pinch. I guess the lesson for me was that, although technology could be great, sometimes it is more important to be practical. Also, this was long before Norway found oil in the North Sea. Norway at the time was a very poor and basically an undeveloped country. There was not much we could brag about and so beating the English to the South Pole made us proud.

My parents were rather strict by today’s standards. At that time, the adults were adults, and the children were children, and not their parents’ best friends. If you have read a book by Robert Paul Smith called “Where Did You Go? Out. What Did You Do? Nothing”, you already have a good description of my youth. At the time it was like two different worlds; the adults, lived in one, and the children in the other. As a child you respected the adults, but you did not confide in them. And probably the adults were too busy making a living to try to understand their children. Should the adult world not approve of something that was going on in the children’s world, corporal punishment was routinely administered. When my brother John and I were very young, my father sometimes had to slap us on our behinds when he came home from work because of something we had done wrong. Spanking was never done in a rage; we accepted it as much as our parents did. That was how things were done, and there were no hard feelings on either side as far as I can remember. I actually treated my own kids the same way my parents treated me, and today I am very proud of the way they all turned out! But times have changed and I am not sure I would have spanked my children if I were raising them in today’s world because it is probably illegal? Looking now at some of my children’s and their peers’ difficulties with their kids — young people who were not raised with these kind of rules — I am convinced that my parents did the right thing. After all, when you do something wrong, and children always try to test their limits, you have to take the penalty. In life and in science, it helps to know the rules so you can figure out when to obey them and when to try and break them.

When I was about 5 years old we moved from an apartment in a village to a small house on a farm — a rather big farm by Norwegian standards, since it was almost 100 acres. It is therefore easy for me to remember my life before age 5 and after age 5 because of that move. The farm my family moved to had 7 horses, about 50 cows that, by the way, all had names, maybe 10 pigs, and an untold number of chickens. One of my jobs was to go down to the barn every evening to fetch milk in a 3-liter bucket. The milk was stored temporarily in a large wooden crate in the barn, and the milkmaid always plunged her naked arm into the milk to fill the bucket. Today this would be unthinkable. My mother would store the milk overnight and skim the cream off it in the morning.

Before I was 5 years old, I remember that my brother John and I shared a room with a maid. My parents were not rich, but almost every family had a maid then, because that was the kind of work that young girls could get. One maid that I remember was named Sofie and she played the guitar and sang every evening. She was part of a religious sect: the Pentecostal Movement. I later found out that she actually became a missionary and died in Africa. When I was very young we lived by a tiny stream, and to get down to it you had to go down a rather steep hill. The hill was overgrown with weeds, and one particular weed burned your skin if you touched its leaves. So we were not allowed to go down there. My brother John and I had a boy playmate whose name was Tor. One day, having nothing better to do, Tor and John pushed me down that hill, and the weeds seriously burned me. My mother rescued me and was mad at my brother and told him that my father, when he got home from work, would penalize him. Then she gave me a small bag containing five pieces of candy. She specifically told me to eat all the candies myself and not to share any of them with John. As I remember it, I ended up giving him two pieces anyway, in spite of my mother’s wishes. At the time, my older brother was my hero, and besides, he promised never to push me down the hill again. I kept this secret from my mother, because I did not think she would approve, and she might also punish John.

It may seem like I was a very rational kid, but I was really terrified of the dark when I was young, and I imagined all sorts of terror while lying in my bed at night. On the wall of that room hung a famous picture; I believe it was from Russia. In the picture, a troika of horses is running while pulling a sled with several people on board. A dozen wolves are chasing the sled in hot pursuit. The people seem doomed, but there is a man in the sled lifting a baby over his head, ready to throw it to the wolves, in order to save the rest of the people. Absolutely not the sort of picture to have hanging in a room where children sleep! This wasn’t the only frightful picture from my childhood. Apparently, the dentist we went to came from the same school of child psychology as my parents; on the walls of his waiting room hung gruesome pictures on how to extract teeth with enormous tongs while friends held you down. As far as I can remember, even though the dentist was my father’s friend, my father never went to the dentist. Who in their right mind would have that horrid imagery on display? This illustrates the two worlds very clearly; the adult world was not very sensitive to children. The gap between our world and my parents can be seen in their attitude towards food as well. John and I ate breakfast and evening meals in the kitchen with the maid, but dinner was always a formal meal that we ate in a dining room with our parents. As a child I had to eat everything served, and clean off my plate. If we did not eat the food, it would be served again for breakfast the next day. I remember a soup made from goose that was very fatty that I struggled with several times at breakfast. I liked dessert and could not understand why my father did not care much for dessert, but that he loved soup. Now that I am an adult, I am the same way. The only food I did not have to eat as a child was a particular Norwegian fish dish, “Lutefisk”, because my father did not like it. It was only served when my father was out of town. Today that dish is one of my favorite meals. So I inherited my love for soup from my father and the Lutefisk dish from my mother. Maybe it has something to do with DNA?

Like most children, I was very excited about my birthday not only because of presents, but also because I could decide what we should have for dinner; I always chose pork patties. The present on my third birthday also stuck in my mind: a blue tricycle. I became very excited, and wanted to try it outside. But a lot of snow had fallen and my mother said no. So I went outside without my tricycle and made a snowball, as the snow was rather wet. Then I put the ball on the ground and began rolling it forward. To my surprise it became bigger and bigger, and some dead maple leaves stuck to the ball. At the time I remember feeling proud and excited about my accidental invention. When I went back inside to report my findings, I was told that people build snowmen by rolling snowballs. But I was thrilled by my discovery nevertheless, because I had done it on my own, nobody had instructed me.

We had a simple outhouse where I lived the first 5 years with two seats. On the farm there were two outhouses, one with 4 seats and one with 6 seats. In each outhouse one or two seats were built low to the ground and thus were suitable for children. Going to the toilet was often a community affair in Norway in those days, and the thinking was why not, since we also eat together! A common sight inside outhouses was a picture of the Norwegian king, King Haakon VII, clipped out from a newspaper. And speaking of newspapers, old newspapers were of course used for toilet paper. You were also guaranteed to see some dirty sexual words written on the walls — words that we never were allowed to say aloud. At the school we had a row of outhouses. The first three outhouses were for boys and the next three for girls. One of my friends used to actually stick his head down into the hole on number 3 so that he could peer over at the bottoms of girls sitting on toilet number 4. I never could do that; I was curious of course, but I could not stand the smell! After we moved to the farm, my family had an indoor toilet also, which was rare at that time. The house we were renting had been recently built by the farmer himself, who would move in when he got too old to work the farm, and he knew the ropes. The farm would then be given to his oldest son; a daughter could only inherit the farm if there were no sons. This was true for the Kingdom of Norway as well, but it has recently been changed to the oldest child. We are slowly moving into a fair world.

As a child I always had a technical bent. For example, I loved to take apart old clocks, locks, and farm machinery just to see how things worked. We had a record player that you had to crank up in order to play a record. It was a wonderful piece of equipment. I got a lot of satisfaction when I figured out how the cranked-up record player controlled the speed of the record. There were three weights attached to levers on a rotating, vertical shaft. At standstill the weights hung straight down. But when you started the record player and the speed picked up, the centrifugal force overcame the gravity, and the weights would rise and move a lever. The lever then applied a force to the brakes that slowed down the rotation. This made the weights start to go down again, but then since there was no braking, the rotation sped up, and so on. Wonderful! In a way I feel sorry for kids growing up today, because they don’t have the opportunity that I did to figure out how things work. For example, if you take apart a modern digital wat...