![]()

PART I

Mathematical Preliminaries

Overview

In this part, I am going to present the main mathematical tool that we will use during the course: constraint optimization. While presenting this material, I will assume that the students are familiar with calculus, matrix algebra, basic logic and set theoretic notations. However, for the reader not familiar with any of these techniques, they, together with some other techniques used in this course, are presented in the Mathematical Appendix in the last part of the book.

![]()

Chapter 1

Constraint Optimization

This chapter introduces reader to constraint optimization technique that is used through the book.

1.1 Constraint optimization with equality constraints

Often in economics, you are asked to maximize or minimize an objective function subject to some constraints. For example, consumers are assumed to maximize their utility given their budget and prices, firms often have to find an optimal way to produce a given quantity of products, which leads to minimizing cost of production taking the level of production, technology, and factor prices as given, etc. One can always turn a constraint minimization into a constraint maximization by changing the sign of the objective function. Therefore, we will formulate all results for constraint maximization problems. Ubiquity of constraint optimization problems in economics comes from the central assumption that economic agents act rationally in pursuing their self-interest. Main mathematical result that allows one to deal with the constraint optimization problems is summarized in the following theorem.

Theorem 1. Let f : X → R be a real-valued function and g : X → Rm be a mapping, where X ⊂ Rn. Let us consider the following optimization problem:

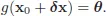

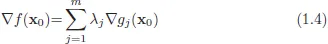

Assume that the solution is achieved at x0 and vectors (∇g1(x0),...,∇gm(x0)) are linearly independent non-degenerate constraint qualifications (NDCQ). Then

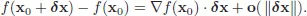

Intuitively, if (1.3) does not hold, one can find point x0 + δx such that

Recall that

Therefore, for x0 to be the optimum ∇f(x0) · δx should be zero. Now, note that locally the surface g(x) = θ looks like a hyperplane and (∇g1(x0),...,∇gm(x0)) forms a basis (by NDCQ) in its orthogonal complement. Therefore,

for some λ1,... , λm.

Proof. Note that NDCQ implies that m ≤ n. If m = n, then vectors (∇g1(x0),...,∇gm(x0)) form a basis in Rn and expansion (1.4) can be found for any vector, including ∇f(x0). Therefore, from now on, we will assume that m< n. NDCQ is equivalent to the statement that the Jacobian matrix J, defined by

has full rank at

x0. Therefore, it must have

m independent rows. Without loss of generality, we will assume that first

m rows of the Jacobian matrix, evaluated at

x0, are independent.

1 Therefore, Eq. (1.3) can be made to hold

for

by choosing

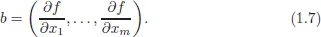

where Jm is an m × m matrix formed by the first m rows of matrix J and

To prove that Eq. (1.3) also holds for

for the same choice of

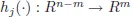

λ, recall that by the Implicit Function Theorem,

2 there exist a neighborhood

3 U of point

x0 and continuously differentiable functions

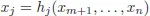

,

such that

for all

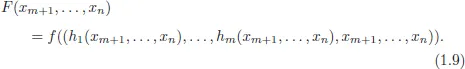

x ∈ U . Moreover,

where

∇n−m denotes vector of partial derivatives with respect to variables

Note that x0 delivers an unconstraint local maximum to function

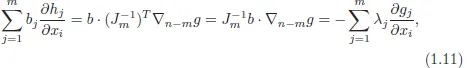

Using the first-order condition for unconstraint optimization and the chain rule, one can write the following:

Note that in matrix notation,

which completes the proof.

1.2 Constraint optimization with inequality constraints

Sometimes, relevant constraints are represented by inequalities rather than equalities. For example, a consumer may be offered a menu of choices. Relevant incentive constraints, which we will discuss later in this course, will specify that she should like the item designed for her at least as much as any other item on the menu. Generalization of the above theorem for the case of inequality constraints is given by the following theorem.

Theorem 2. Let f : X → R be a real-valued functional and g : X → Rm be a mapping, where X ⊂ Rn. Let us consider the following optimization problem:

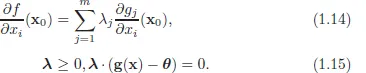

Assume that the solution is achieved at x0 and vectors (∇g1(x0),...,∇gm(x0)) are linearly independent (NDCQ).Then

This statement is known as the Kunh–Tucker theorem. Intuitively, the first-order conditions state that the gradient of the objective function should look in a direction in which all the constraints are increasing, since otherwise one can move in a direction that will leave the choice variable x within the constraint set, but increase the value of the objective. I will not give the complete proof of this theorem. However, it is quite easy to see intuitively why it is true. Indeed, if a certain constraint does not...