![]()

A Short History of Adenovirus | 1 |

1.1 Discovery and Initial Characterization

The viruses we now know as adenoviruses were first described over 60 years ago, when the medium from cultures of adenoids of young children in Washington D.C. that underwent degeneration within 1–4 weeks after isolation was shown to contain a filterable agent (i.e. a virus) that transmitted the cytopathic effect to established human cells lines, such as HeLa cells (Rowe et al., 1953). An agent that induced very similar cytopathic responses was isolated the same winter from the throat washings of a military recruit diagnosed with primary atypical pneumonia (Hilleman et al., 1954). This respiratory illness (R1) and the adenoid-degenerating (AD) agents were found by neutralization and complementation fixation assays to be antigenically related. Over the next few years, additional viruses that share a group-specific complement fixation antigen were isolated from multiple human subjects, including apparently healthy individuals (Fox et al., 1969; Fox et al., 1977; Wold & Ison, 2013), from other mammals, such as monkeys (Hull et al., 1958), dogs (Kapsenberg, 1959) and mice (Hartley & Rowe, 1960), and from birds (Yates & Fry, 1957). The family name adenovirus (Adenoviridae) was chosen in 1956, in part because of its echo of the tissue of origin of the prototype strain.

Adenoviruses are non-enveloped virus particles with diameters of 70–90 nm, with a distinctive morphology first visualized by electron microscopy of a species C human adenovirus (HAdV-C5) (Horne et al., 1959). In contrast to many viral capsids with icosahedral symmetry, adenovirus particles actually have an icosahedral appearance. Furthermore, they carry distinctive fibers projecting from each of the 12 vertices of the particle (one, two, or three fibers/vertex, depending on the genus). Adenoviral genomes are linear, double-stranded molecules of DNA that carry inverted terminal repetitions (ITR), a packaging signal (ψ), and a viral protein, the terminal protein (TP), covalently linked to the 5′ end of each strand. Despite these common properties, and a conserved core of protein coding sequence, adenoviral genomes differ in size (ranging from ~26 kbp to >48 kbp), GC content and arrangement, and sequences of non-conserved genes (see Chapter 5).

1.2 Classification and Evolution

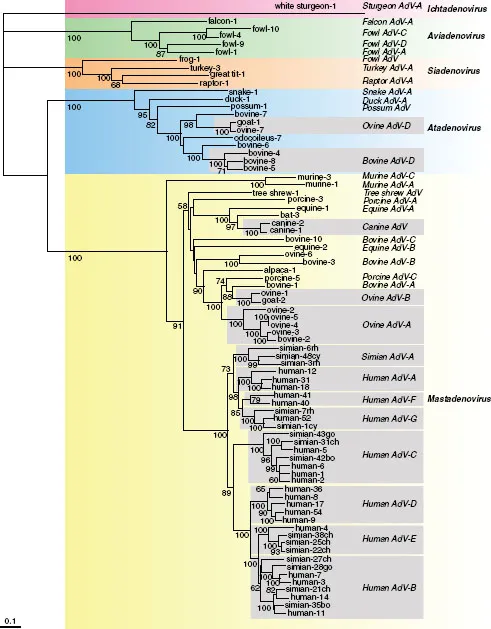

Adenoviruses have been identified only in vertebrates, from fish to mammals. Viruses isolated from humans dominate the family, and only small members of piscine and reptilian viruses have been reported to date, a bias that almost certainly reflects intensity of study, rather than the actual distribution of members of this family. The ~170 distinct members recognized by the International Committee on the Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV) have been classified in five genera (Harrach et al., 2012). The criteria for classification have included the species of the host, serological properties, AT content of the genome, sequence relationships among genomes, and organization and coding capacity of the genome. For example, some structural proteins (core protein V and cement protein IX) are unique to the Mastadenovirius. Similarly, the genes that encode viral regulatory proteins differ considerably among the genera. Phylogenetic comparisons of sequences encoding specific proteins, typically those of hexons, have identified five discrete clades that correspond to the five genera (Fig. 1.1).

In general, adenoviruses appear to have co-evolved with their hosts; phylogenetic trees for the viral protease and host mitochondrial rRNA are similar, as are the evolutionary distances between the viruses within a genus and their hosts (Benko & Harrach, 2003; Harrach et al., 2012; Kovacs et al., 2003). Nevertheless, these relationships are by no means absolute. For example, adenoviruses that infect birds or mammals can belong to different genera (Fig. 1.1). In the absence of any adenovirus isolated from an invertebrate species, the early evolutionary history and origin of this virus family remain a matter of speculation. However, adenoviruses exhibit some striking similarities to various bacteriophages; the topology of the major capsid protein (hexon) and overall capsid architecture, described in Chapter 2, closely resemble those of the double-stranded DNA tectivirus PRD1 (Benson et al., 1999), which infects Gram-negative bacteria. Furthermore, the unusual mechanism of protein priming of viral DNA synthesis (Chapter 6) is also shared by these two virus families, as well as with bacteriophage ø29, a podovirus (Benson et al., 2003; de Jong et al., 2003; Pecenkova et al., 1999).

1.3 Human Adenoviruses

1.3.1 Classification

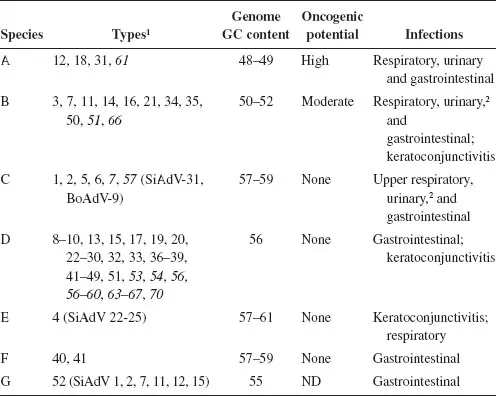

HAdVs are all classified within the genus Mastadenovirus, and were originally ordered into subgroups on the basis of serological criteria, GC content of the genome, and oncogenicity in rodents. The subgroups are now designated species. With the application of more modern criteria, including genome sequence analyses (Robinson et al., 2013a), phylogenetic distance (typically based on the amino acid sequence of the DNA polymerase), and the ability to recombine, seven HAdV species (A–G) have been defined (Table 1.1). Some simian adenovirus serotypes have proved to be so closely related to specific human isolates that they are included with human species; for example, simian adenoviruses 21 and 31 in human species B and C, respectively. As discussed below, this grouping of HAdVs on the basis of genetic and genomic parameters is mirrored, at least in part, by such biological properties as pathogenesis and oncogenicity.

The classical serological methods of neutralization of virus infectivity by serum antibodies (serum neutralization) and inhibition of hemagglunitation activity initially distinguished 51 HAdV serotypes (Lion, 2014; Wold & Horwitz, 2006). Hemagglutination is a property of the fiber (Nicklin et al., 2005), whereas the majority of epitopes recognized by neutralizing antibodies lie within the seven hypervariable loops of the hexon (the major capsid protein) (Roberts et al., 2006). These classic assays are relatively time-consuming, require the availability of appropriate sera and report on only a small fraction of the genetic diversity among HAdV isolates. Consequently, they have been increasingly replaced by typing methods based on sequencing of segments of the genome that specify type-specific epitopes of the hexon or fiber (Lion, 2014; McCarthy et al., 2009) and complete genome sequencing (Seto et al., 2011). With decreasing cost and increasing power, full genome sequencing is now quite feasible, and obviously provides far more information than can be obtained by focus on type-specific epitopes and the regions that encode them. Full genome sequencing has resolved apparently anomalous results obtained by serotyping (e.g. Liu et al., 2012; Walsh et al., 2010). This approach also facilitates characterization of newly arising recombinants, which are particularly prevalent within species D, the largest group (Robinson et al., 2013a).

The designation serotype has been replaced by the term type, and there is general agreement that genome sequence information should be the basis for the identification of new HAdV types. Indeed, the types numbered from 52 were detected and characterized by sequencing methods (see Lion, 2014). Nevertheless, there is ongoing debate among members of the adenovirus research community about how much sequence information should be collected, the contribution of serological methods, and how new HAdV types should be named and by whom (Aoki et al., 2011; Kajon et al., 2013; Lion, 2014; Seto et al., 2011; Seto et al., 2013).

As of this writing, June, 2016, more than 70 HAdV types have been reported. Their distribution among species is highly skewed, with but one representative of both species E and G, and over 40 types in species D (Table 1.1). The sole member of species E, HAdV-E4, was one of the first HAdVs to be isolated (Hilleman et al., 1954), and was originally placed in species B. However, recent computational analyses exploiting the availability of genome sequences of all human prototypes and various SAdVs (e.g. Robinson et al., 2013b) established that this isolate is unique, and arose by recombination and zoonosis; the HAdV-E4 genome contains sequences for hypervariable hexon loops L1 and L2 from HAdV-B16 (hence its original classification) in the backbone of a simian adenovirus (Dehghan et al., 2013). Similarly, although both species F and G types are associated with gastroenteritis (Table 1.1), phylogenetic analyses of genome sequences have established that HAdV-G52 is quite distinct from the members of species F (Jones et al., 2007).

Homologous recombination between highly related sequences in the genomes of members of the same species has been recognized and exploited for decades (e.g. Sambrook et al., 1975; Takemori, 1972). Recombination within the coding sequences for hexon, penton, and fiber is common (Lion, 2014; Lukashev et al., 2008; Robinson et al., 2011b; Robinson et al., 2013b), but has also been observed in the E3 region (Singh et al., 2013). Species D HAdV types appear to be especially prone to recombination; the more recently identified members of this species have been shown by sequencing and bioinformatic analyses to have arisen by recombination between the genomes of two or more HAdV-D types (Kajon et al., 2014; Kaneko et al., 2011a; Matsushima et al., 2013; Robinson et al., 2013b). This property implies that co-infection of a single cell by two (or more) HAdV types, a pre-requisite for recombination, is not infrequent, perhaps because these viruses can persist in immunosuppressed patients. Duplication and divergence of sequences, as well as deletion, contribute to the evolution of genetic diversity in HAdVs (Davison et al., 2003; Jones et al., 2011) and substitutions may be important in some cases (Robinson et al., 2013b). However, it is clear that recombination is the predominant mechanism for the generation of new HAdV types (see Lion, 2014; Robinson et al., 2013b), which are associated, in many cases, with distinct pathogenic properties.

1.4 Prevalence and Pathogenesis

Members of the Adenoviridae are widespread in the human population and present in all parts of the world, with different types of predominating in particular geographic regions or at different times (see Lion, 2014; Wold & Ison, 2013). They are associated with a variety of acute diseases in normal individuals.

Infection of epithelial surfaces by HAdVs causes respiratory disease, epidemic keratoconjuctivitis, and gastroenteritis, and is associated with a variety of other syndromes (Chapter 8). There is some correlation of the pathogenicity of these viruses with the other properties on which classification is based. For example, species B and C HAdVs cause acute respiratory disease, and pneumonia and pharyngitis, respectively. In contrast, epidemic keratoconjunctivitis is associated largely with species D and E types, and gastroenteritis with the members of species F and G. At present, there is no explanation for such differences in tropism and pathogenicity, although it is clear that they cannot be ascribed to a single interaction with the host, such as binding of virus particles to different, cell type-specific receptors (Chapter 3). Consequently, it is more likely that HAdV tissue tropism and disease are determined by multiple aspects of virus-host interactions.

As described in Chapter 8, HAdV infections can be endemic; for example, several species C types in young children, or epidemic, such as outbreaks of keratoconjunctivitis or of acute respiratory disease in the military. Infection by these viruses can lead to significant morbidity, a situation that prompted the U.S. Department of Defense to support the development and redeployment of a vaccine against HAdV-4 and HAdV-7 (Gaydos et al., 1995; Gray et al. 2000; Radin et al., 2014). However, HAdVs are a far more serious problem in immunocompromised individuals, such as transplant recipients and those infected with immunodeficiency virus type 1. In such populations, morbidity is markedly increased, and death is a not infrequent outcome of infection (Echavarria, 2008; Lion, 2014; Wold & Ison, 2013).

1.5 Lessons from Adenovirus

1.5.1 Insights into fundamental cellular processes

The demonstration that HAdV-C2/5 genes, like cellular protein-coding genes, are transcribed by host cell RNA polymerase II (Price & Penman, 1972; Weinman, 1974) prompted a cohort of investigators to turn to adenovirus-infected cells to study the mechanisms by which mRNA is synthesized in mammalian cells. Indeed within just a few years, intensive characterization of viral mRNAs and the sequence that encode them in the species C HAdV genome solved the long-standing conundrum of how mRNAs could be produced from considerably longer precursors (pre-mRNA...