![]()

Additional/Supportive Information

Appendix 1: Basic Deterministic Chaos Concepts

Appendix 2: Basic Complexity and CAS/CAD Concepts

Appendix 3: Some Simple Mathematical Illustrations

Appendix 4: Some Prominent Complexity Pioneers/Researchers and their Contributions

Appendix 5: Gaia, Human Beings and the Brain’s Evolution

Appendix 6: Integrating Intelligence/Consciousness Management, Knowledge Management, Organizational Learning and Complexity Management

Appendix 7: Key Terminologies and Concepts (Complexity Theory, Intelligent Organization Theory, and Relativistic Complexity Theory)

![]()

Appendix 1

Basic Deterministic Chaos Concepts

1 Introduction

1a What is (deterministic) chaos theory?

Deterministic chaos theory or chaotic dynamics (a branch of mathematics) is the study of relatively low dimensionality chaotic systems captured by one or more difference equations (discrete chaotic systems — chaotic characteristics start with dimension 1 systems) or differential equations (continuous chaotic systems — chaotic characteristics start with dimension three systems) — see Poincare–Bendixson theorem in Appendix 7. Discrete chaotic systems manifest bifurcation, while continuous chaotic systems undergo transition. Thus, chaotic systems are nonlinear dynamical systems whose state changes with time nonlinearly (low dimensionality deterministic chaotic systems — sensitive dependence on initial conditions — deterministic not random, but unpredictable).

1b What are linear/nonlinear dynamical systems?

In general, there are two different ways of perceiving dynamical systems (constantly changing/evolving). They are as follows:

i. Dynamical Systems

• Linear, closed conservative systems

• Dissipative, open, nonlinear systems

ii. Dynamical Systems

• A set of processes (dynamic)

• A set of states (outcome)

From the latter perception, the study of dynamical systems focuses on the collection of all its states (phase space) and its constantly changing dynamics (although, some early scientists perceived chaos as a science of process rather than state, that is, of becoming rather than being). In chaos theory, chaos is a certain dynamical phenomenon or chaotic motion (from simplistic to deterministic chaotic) that happens when a chaotic system changes with time (discrete-time or continuous-time). Hence, the term chaos (as defined by Li and Yorke in 1975) is not a state.

1c Deterministic chaotic systems and the chaotic dynamic

Deterministic chaotic systems (DCS) are a type of nonlinear dynamical systems that have a small number of variables (mathematical) — low dimensionality simple deterministic systems/models that manifest chaotic behavior (deterministic ≠ predictable). DCS can be stable for a period of time (predictable) and then manifesting chaotic changes (unpredictable). Some common examples of simple chaotic systems are as follows:

• Logistic map (a difference equation — mathematical system, discrete-time)

• Henon map (a set of difference equations — mathematical system, discrete-time)

• Lorenz waterwheel (mechanical system, continuous-time)

• Water in a container with heat supply (physical system, continuous-time)

• Double rod pendulum (physical system, continuous-time)

• Lorenz convection system (nature/environmental system, continuous-time)

In real world DCS, the variables (at least one variable/parameter must be nonlinear — for instance, the relationship between speed and friction is nonlinear) of such a system interact in a chaotic nonlinear manner (also associated with the microscopic entities are clear but the macroscopic behavior is difficult to comprehend) leading to a deterministic but not predictable output. It is deterministic because when inputs are known, the output can be computed accurately. However, if an estimated input is used, the output can be totally different, that is, a small change in input can produce a totally different output — leading to unpredictability — sensitive dependence on initial conditions — a divergent process — butterfly effect (see 2b) — first observed by Edward Lorenz in his weather system.

A chaotic system also possesses the property of interdependency (high interconnectedness among the variables). Discrete-time chaotic systems changes in state through a discrete process called bifurcation (see 2c) — chaotic attractor. In addition, there are also certain preferred states that form strange attractors (see 2d and 2e). An attractor is a set of states and a subset of the phase space. The first strange attractor that is not a mathematical strange attractor is the Lorenz attractor of his three-dimensional convection system (physical system) — observed by Edward Lorenz in the 1960s (although some mathematical strange attractors have been observed earlier).

Hence, in general, the chaotic dynamic/motion changes from simplicity to deterministic chaotic (relatively low finite randomness, not infinite randomness) which is unpredictable due to the butterfly effect, and interdependency of variables, leading to the emergent of chaotic attractor and/or strange attractor.

2 Further Discussion on Properties of Chaotic Systems

Deterministic chaotic systems are inherently sensitive dependence on initial conditions (exhibiting the butterfly effect) due to the presence of nonlinear variable(s). As indicated earlier some other characteristics of DCS include bifurcation, far-from-equilibrium and presence of chaotic attractor. These characteristics are further illustrated below.

2a Linearity and nonlinearity

The essence of linearity is the proportionate relationship between cause and effect (in mathematics, a simple linear equation is y = x + 1 where x is the cause and y denotes the effect) — see Appendix 3. A small input leads to a small output, and larger inputs leads to larger outputs. A linear equation can be easily ‘solved’, and a linear system could be ‘dismantled’ and ‘assembled’ (Cartesian belief, reductionism and fundamentalism) again without changes in properties.

However, for a nonlinear system, the direct proportional relationship is no longer true (nonlinearity). Consequently, in a nonlinear system, starting points that are close to one another may result with rather ‘distant’ ending points (for instance, for a power/exponential equation y = x2, when x = 1, y = 1, but when x = 3, y = 9 — a simple nonlinear relationship).

In is important to note that finite dimensional linear dynamical systems are never chaotic. Chaotic behavior only emerges in nonlinear or infinite dimensional linear dynamical systems. The latter is in-deterministic chaotic systems.

2b Sensitive dependence on initial conditions (butterfly effect)

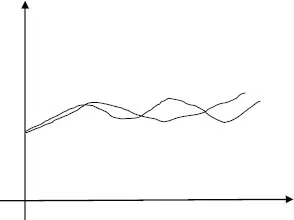

Lorenz (through his weather system) is the first to recognize that chaotic systems are sensitive to initial inputs. The slightest initial difference, if amplified repeatedly (by both positive and negative feedbacks) may lead to highly unpredictable behavior/output (see Figure 1A.1 for a simple illustration). At the initial stage of the diagram the outputs of the two curves are about the same for the same initial inputs. At a later stage, their outputs are substantially different for approximately the same inputs. This phenomenon of repetitive amplification due to iterations leads to the consequence known as the butterfly effect. Thus, the sensitive dependence on initial conditions attribute of a DCS renders its output unpredictable.

Figure 1A.1 A simplified illustration of sensitive dependence on initial conditions (butterfly effect).

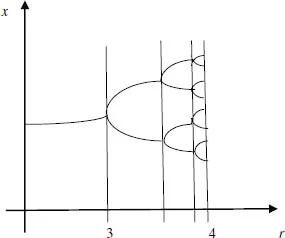

2c Bifurcation

Bifurcation is splitting into two paths, and it is a unique way that discrete-time chaotic systems behave. The system becomes chaotic when the bifurcating process accelerates rapidly increasing the number of paths from 1 to 2, 4, 8, 16, 32, …, (chaotic attractor). A commonly studied chaotic system that is frequently used to illustrate bifurcation is the logistic map — a discrete chaotic system. Mathematically, the logistic map (dimension one, degree 2) is a relatively simple equation, xn+1 = rxn(1 − xn) where xn is between 0 and 1, and r (bifurcation nonlinear parameter) is a positive number (interest value, 0 ≤r ≤ 4). The characteristic of bifurcation indicates that a variety of different paths are opened up before the system. At the 4th bifurcation point the logistic map moved into deep chaos — chaotic attractor (see the simplified bifurcation diagram — Figure 1A.2) — also see Appendix 3.

In 1978, Feigenbaum published his theoretical study on bifurcation, including period doublings, the computation of the (first) Feigenbaum constant (≈ 4.6692, a universal constant) and universality using the logistic map. The constant is the ratio of the length between two consecutive points of bifurcation.

Figure 1A.2 A simplified illustration of bifurcation — at 4th bifurcation the system is highly chaotic.

2d States/attractors/phase space of nonlinear dynamical systems

An attractor (a set of states) is a subset of the phase space (the set of all the states of the system) of dynamical systems. Dynamical systems possess four types of attractors as follows:

• Point attractor

• Periodic (limit cyclic) attractor

• Strange/chaotic attractor

• In-deterministic chaotic attractor

A point (dimension zero) and periodic attractors have been observed in simple linear physical systems (dimension two and below). When a marble is rowed along the side of a bowl it will circulate continuously in the bowl moving towards the lowest point. This lowest point is a point attractor (one state). Similarly, the pendulum of a ‘charged’ old grandfather clock possesses a two-point periodic attractor (at the two extreme ends of the swing) — see Appendix 3 for simple mathematical illustrations. The strange/chaotic attractor was discovered last in mathematical chaos. (All chaotic attractors are strange attractors, but not vice versus.)

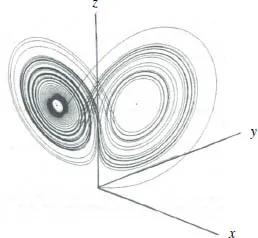

2e Strange attractor

As stated earlier, in dynamical systems, there are four types of attractor namely, point (fixed), periodic (cyclic), strange/chaotic, and in-deterministic chaotic. In physical systems (dimension two or less) the fixed/point attractor and periodic attractor are very common. In higher dimension nonlinear systems, the attractor could be a curve, a manifold (a topological space), or a set with fractal structure. In mathematics, the evolving variables of an attractor (in finite dimensional systems) are represented by an n-dimensional vector.

A commonly illustrated example of a strange attractor is the Lorenz attractor — its phase diagram (3D) is a deep spiral that never intersects, and is confined in a finite three-dimensional space (see Figure 1A.3) — converges to an attracting set. The path appears to be infinity long (with a significant depth) that never intersects itself (diverge from other nearby orbits), and the attractor is scale invariance (see strange attractor Appendix 7). In a human society, sociality is a biological attractor. A strange attractor is a ‘stable’ state.

Figure 1A.3 The 3D Lorenz strange attractor.

2f Far-from-equilibrium

Far-from-equilibrium systems do not return to their earlier regular states, they never repeat themselves, and they are nonlinear. Thus, such systems are never in static equilibrium. The nonlinear interactions in far-from-equilibrium open systems allow the systems to pass from one basic state to another by bifurcation and transitions. In this respect, the far-from-equilibrium characteristic in nonlinear interdependent dynamical systems is both the source of chaos and renewal.

Notes : Some Significant Properties of DCS:

• Sensitive dependence on initial conditions (butterfly effect)

• Deterministic but not (limited) predictable (presence of surprises)

• Nonlinearity (variable and/or parameter)

• Bifurcation (discrete-time), or phase transition (continuous-time)

• Interdependency (strong coupling among agents/variables)

• Chaotic attractor and/or strange attractor

• Far-from-equilibrium

• Deterministic chaotic dynamic — simplicity to chao...