![]()

Chapter 1

Turning Point I

The 2012 ASEAN Fiasco and Its Aftermath

The failure of ASEAN foreign ministers to issue the traditional joint communiqué at the end of their 2012 annual meeting in Cambodia was due to differences over the South China Sea disputes. Unprecedented, it marked a turning point, a tremor, in geopolitical relations in the region since China unveiled its “nine-dash line” claim on the South China Sea by filing two notes verbales at the United Nations in 2009. If China’s notes verbales were the tectonic shift in the South China Sea disputes, the 2012 ASEAN fiasco was its first geopolitical aftershock, with reverberations still being felt by ASEAN.

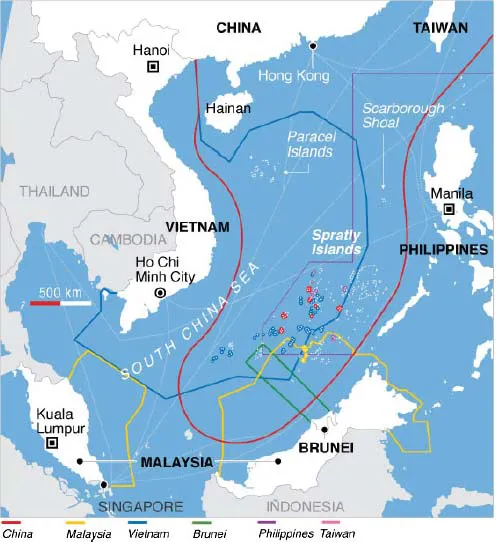

The territorial claims in the South China Sea by the different claimants.

Source: http://blogs.voanews.com/state-department-news/2012/07/31/challenging-beijing-in-the-south-china-sea/

![]()

CHAPTER 1.1

| After the Phnom Penh AMM Disaster: Can ASEAN Regain Its Cohesion? | Tan Seng Chye |

SYNOPSIS

The failure of the ASEAN Ministerial Meeting (AMM) in Phnom Penh to issue a joining communiqué showed the deep divisions in ASEAN over the South China Sea disputes. This would affect ASEAN’s ability to deal with the emerging big power rivalry in the region, which could undermine ASEAN’s unity and solidarity, and its role of promoting cooperation among its members.

COMMENTARY

THE SHOCKING outcome of the ASEAN Ministerial Meeting (AMM) in Phnom Penh in July 2012 was a significant watershed in ASEAN’s history. It was the first time since its establishment in 1967 that ASEAN was so divided over one issue that it prevented ASEAN from issuing the usual Joint Communique at the end of the AMM. In the past, ASEAN had always been able to arrive at some compromise in the “ASEAN way”. Its failure to do so this time reflected the seriousness of the situation.

The media reports before and during the AMM were about the differences among some ASEAN members over the territorial disputes in the South China Sea which dominated the AMM, instead of the more important issues of economic and other functional cooperation in ASEAN. The Philippines and Vietnam were reported as wanting to include in the communique references to the recent marine incidents in the South China Sea involving their ships and Chinese vessels. Cambodia, as Chairman, argued that such mention of bilateral disputes was not appropriate for the AMM communiqué.

Divisions within ASEAN — Lack of Cohesion and Solidarity

The issue overshadowed ASEAN’s efforts to make progress towards an ASEAN Economic Community in 2015. ASEAN Secretary General Surin Pitsuwan said that, in not being able to issue the joint communiqué, the AMM could not record the issues and proposals for the ASEAN Summit’s consideration and decisions later in the year. This development showed ASEAN’s lack of cohesion and solidarity in pursuing issues of common interest to ASEAN, unlike in the past.

What happened at the recent AMM should be taken seriously by ASEAN as a wake-up call. For the first time, certain individual ASEAN countries were prepared to pursue their own interest to the extent of disregarding ASEAN’s cohesion and practice of finding a compromise for ASEAN’s common interests. This issue has become more challenging for ASEAN because of the emerging big power rivalry in the region including in the South China Sea. ASEAN is entering a new era of big power rivalry from which it has tried to keep away since its establishment. ASEAN should now reflect on the new situation and consider the way forward to ensure ASEAN cohesion and to maintain its important role in the region.

Over the years, ASEAN had been able to establish its importance and relevance as a neutral platform and a convenor for the major powers to meet with ASEAN countries and among themselves. ASEAN centrality was recognised in the multi-layered regional institutions architecture like the ASEAN+1, ASEAN+3, ARF, EAS and ADMM Plus. These have enabled ASEAN to cooperate among themselves and with the major powers to build a peaceful and prosperous region, thus enhancing the importance of ASEAN regionally and internationally.

The South China Sea disputes were complex and complicated as the claims were not only territorial but also historical in nature. As such, the South China Sea disputes would not be resolved for a long time to come. The South China Sea disputes involved only four ASEAN countries with China and Taiwan, and is not an ASEAN–China problem. ASEAN’s approach had been that the disputes should be resolved peacefully among the claimant states in accordance with international law and UNCLOS, supported by the Declaration of Conduct of Parties in the South China Sea (DOC) and the Implementing Guidelines of 2011.

ASEAN and China were working towards a Code of Conduct to facilitate negotiations among the claimant states to resolve their disputes. Freedom of navigation was never a problem through the South China Sea as all regional countries as well as the major powers had a stake to ensure freedom of commercial navigation as about half of the world’s trade and energy pass through the Southeast Asia region.

Emerging Big Power Rivalry — Challenges for ASEAN

Aside from the South China Sea disputes, the expanded EAS was another area of concern as the EAS meeting in November 2011 has shifted the agenda to political and security from the earlier economic and functional cooperation pursued by the EAS. Thus, future cooperation in the expanded EAS was uncertain and ASEAN centrality could be challenged if it could not set the agenda and drive the process.

The new era of emerging big power rivalry in the region involved the US’ enhanced engagement in the Asia region and its pivot or rebalancing of its military forces to Asia Pacific as well as China’s response to the US strategy to conscribe it. This rivalry had an impact on ASEAN as already evident in the US intervention in the South China Sea disputes at the ARF meeting in July 2010, and China’s refusal of external involvement or even regional participation in its bilateral disputes.

The AMM had been distracted from its main purpose and objectives by the South China Sea disputes which would not be resolved for a long time to come. ASEAN countries should recognise that continued ASEAN cooperation in economic and other functional areas and ASEAN’s unity are so important to the well-being of all its members. In the past, ASEAN had been able to progress as it could always find a compromise through the “ASEAN way” when they encountered differences. Looking forward, ASEAN should review what had happened at the AMM and in recent times, and consider how it could regain its cohesion and solidarity for ASEAN to maintain its relevance and role in the region to further ASEAN’s interests.

Tan Seng Chye is a Senior Fellow at the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies, Nanyang Technological University. An earlier version of this was published in RSIS Commentary on 16 July 2012.

![]()

CHAPTER 1.2

| Navigating Turbulent Waters Post-Cambodia: Can ASEAN Tame China? | Yang Razali Kassim |

SYNOPSIS

The fracas in ASEAN over the South China Sea disputes was symptomatic of possible turbulence ahead for the regional organisation as it steered its relations with Asia’s emergent power.

COMMENTARY

ON THE 45th anniversary of ASEAN on 4 April 2012, Indonesia’s Foreign Minister Marty Natalegawa expressed optimism that a regional code of conduct to govern behaviour in the South China Sea would be ready by year’s end. In so doing, he signalled ASEAN’s shift to a new and more active phase to resolve the territorial disputes in the South China Sea by pushing for an early adoption of the long-stalled Code of Conduct (CoC). Dr Natalegawa’s confidence followed his success in securing an ASEAN consensus on a six-point statement of principles on the South China Sea in late July after it failed to issue a joint communiqué at the group’s annual meeting in Phnom Penh.

The statement however papered over the rift within ASEAN between members who were disputants in the South China Sea and the ASEAN chair who refused to seek a compromise position, resulting in the non-issuance of a joint communiqué for the first time in ASEAN’s 45 year-long history. Cambodia would need to focus on repairing the fissures in ASEAN so that it could host a credible Summit in November that same year.

Damage Control: ASEAN’s Three Concerns

By shifting gear towards an early CoC, ASEAN was also repairing the rift over the territorial disputes between some of its members and China, the region’s emergent power. This had prompted a more cooperative posture on Beijing’s part. China’s Foreign Minister Yang Jiechi, on a visit to Jakarta on 10 August 2012, pledged to build mutual trust towards the eventual adoption of the CoC.

Notwithstanding its common position, ASEAN would need to regain its unity of purpose to assert its direction. “You can only have an ASEAN that is central in the region if ASEAN itself is united and cohesive,” said Dr Natalegawa. Unity was crucial for ASEAN to realise its larger goal of an ASEAN Community in 2015, while a united ASEAN was essential for its role as a central player in the evolving East Asian economic and security architecture.

ASEAN, however, was not totally free of troubles as the region entered a period of great uncertainty. The Phnom Penh episode had exposed three concerns, first and foremost being an intra-ASEAN rupture.

For some time since the expansion of the group to 10 in the late 1990s, there has been talk of a “two-tier ASEAN” developing. One is the core ASEAN comprising the original five founding members Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand, Singapore and Philippines plus Brunei, which joined in 1984.

The other was the new outer layer of ASEAN, which comprised four Southeast Asian states that were once on the periphery of ASEAN — some even ideologically opposed — and were incorporated after the end of the Cold War. Collectively, they are referred to as the CLMV countries — Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar and Vietnam.

The incorporation of the CLMV states was prompted by the vision of ASEAN’s founding fathers of a unified Southeast Asia. Some members were, however, concerned about too fast an expansion. Could the CLMV countries, being essentially socialist or central command states, fit into the norm, political culture and values of mainstream ASEAN? However, the regional unifiers were persuasive and won the day.

Indeed, over the following decade, an expanded ASEAN made its mark on the wider region, paving the way for such initiatives as the ASEAN+3 (China, Japan and South Korea). A unified Southeast Asia developed such confidence that ASEAN even pursued the ambitious diplomatic strategy of becoming central to the wider regional architecture, exemplified by the East Asia Summit.

Strains Waiting to Show

The expansion, however, came with strains. Firstly, Myanmar’s inclusion, which upset ASEAN’s Western partners, came at a cost to mainstream ASEAN. The diplomatic dividend was a reforming Myanmar, albeit still fragile. Secondly, Cambodia was proving to be a difficult addition. Since ASEAN’s founding, members had squabbled over bilateral disputes, but never had they resorted to a “shooting war”.

For the first time in 2008, however, when Cambodia and Thailand clashed over a border dispute, shots were fired. The easy and unprecedented slide to armed conflict, harking back to historical animosities, was ominous. Was there a deeper problem between mainstream ASEAN and outlier ASEAN?

The second-tier, as initially feared, had brought in a new set of challenges. Some argue these are growing pains that should be accommodated. The failure of the Phnom Penh meeting to issue a joint communiqué was reflective of the widening divide within. No core ASEAN member in the role of chair would have allowed the annual meeting to close without a joint communiqué, which was an important record of key decisions.

A core ASEAN member would have resorted to some finessing of diplomatic language in the text to reflect common concerns. The ease with which the Cambodia chair tossed aside the joint communiqué was again reflective of a deeper problem — did the CLMV countries have the same commitment to ASEAN and all that it stood for?

China’s Growing Intrusion

The second concern is the impact of this fissure on the creation of the ASEAN Community 2015. This project was on the brink of falling apart. ASEAN Community 2015 now very much hinged on who would chair the group over the next three years. On record, they were Brunei, Myanmar, and Malaysia in that order. Brunei and Malaysia are members of mainstream ASEAN; Myanmar is not. Indeed, Myanmar would be steering ASEAN at a sensitive moment in the group’s evolution. Would Naypyidaw be next to pull a shocker? The third source of concern is China’s growing intrusion into the foreign policy making domain of ASEAN. It is clear that Beijing had leaned on Phnom Penh, a close ally, to influence the handling of the South China Sea disputes in ASEAN’s joint communiqué. What China had done will ...