![]()

CHAPTER 1

The Development of Wind Converters

1.1Nature and Origin of the Wind

The wind is the motion of a mass of air. For the purpose of using wind energy, it is normally the horizontal component of the wind that is of interest. There is also a vertical component of the wind that is very small compared with the horizontal component, except in local disturbances such as thunderstorm updrafts.

1.1.1Atmospheric pressure

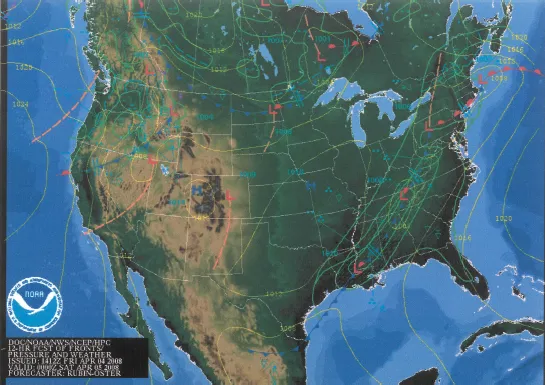

At the earth surface, the atmospheric pressure is measured in the unit Pascal(Pa) and has an average value 101,325 Pa, which is sometimes called “one atmosphere”. Another unit of pressure used for meteorological calculations is the millibar (mbar). There are exactly 100 Pa per millibar so that one atmosphere is about 1,000 mbar. On a map, regions of equal atmospheric pressure are identified by isobar lines such as those illustrated in Fig. 1.1. A close concentration of isobar lines indicates a high pressure gradient or region of rapid pressure change. Wind speed is directly proportional to the pressure gradient.

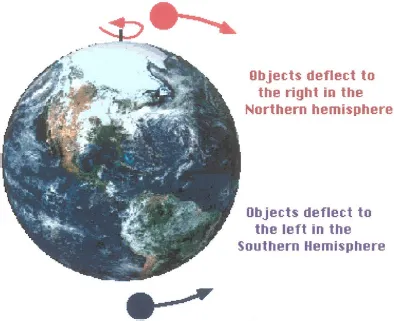

The atmospheric pressure varies from place-to-place and from day-to-day, caused by the combined effects of solar heating and the rotation of the earth. As the earth spins, illustrated in Fig. 1.2, the atmospheric air surrounding it is dragged round with it at different levels depending on altitude. The mix of air forms turbulence causing wind at the earth surface.

1.1.2The Coriolis effect

Winds blow across the earth from high-pressure systems to low-pressure systems. However, winds do not travel in a straight line. The actual paths of the wind — and of ocean currents that are pushed by the wind — are partly the result of the so-called Coriolis effect, named after a 19th century French mathematician.

Fig. 1.1Atmospheric pressure isobars for North America, April 2008.2

A feature of rotational systems is an inertial effect known as the Coriolis effect. The earth rotates faster at the equator than it does at the poles. When air moves over the surface of the moving earth, as it rotates, instead of travelling in a straight line the path of moving air appears to veer to the right.1

The effect is that air moving from an area of higher pressure to an area of lower pressure moves almost parallel to the isobars. In the northern hemisphere, the wind circles in a clockwise direction towards the area of low pressure but in the southern hemisphere, the wind circles in an anti-clockwise direction, as shown in Fig. 1.2.

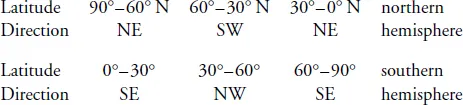

The heating effect of solar radiation varies with latitude and with the time of day. The warming effect is greater over the equator causing less dense warmer air to rise above the cooler air, reducing the surface atmospheric pressure compared with the polar regions. The combined effect of the solar heating and the Coriolis effect is to create the following prevailing wind directions.2

Fig. 1.2The Coriolis effect on wind direction.2

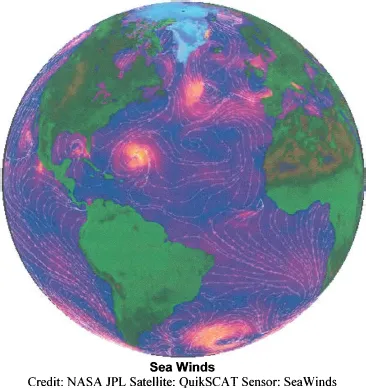

In any particular location, the wind direction is much influenced by the presence of land masses and features such as mountain ranges. The general picture of sea winds for the north and south Atlantic regions is shown in Fig. 1.3.2

1.2Development of Wind Converters

Wind energy provided the motive power for sailing ships for thousands of years, until the age of steam. The fortunes of the European colonial powers such as England, France, Germany, Spain, Portugal, Holland and Belgium rested on their mastery of the sea and its navigation. But the intermittent nature and uncertain availability of the wind combined with the relative slowness of wind powered vessels gradually gave way to fossil-fuel powered commercial shipping. Today, most shipping uses oil fuelled diesel engines.

Fig. 1.3Global wind distribution.2

However, yachting and small boat sailing remain important recreational sports throughout the world.

The wind has also been used for thousands of years to provide the motive power for machines acting as water pumps or used to mill or grind grain. Such machines came to be known as “windmills”. The operators of windmills in feudal England took the name of their craft and acquired the surname Miller (or Millar).

Very early wind machines were vertical axis structures and have been identified in China, India, Afghanistan and the Middle East, especially Persia, going back to about 250 B.C. and possibly much earlier.

Horizontal axis wind machines were developed by the Arab nations and their use became widespread throughout the Islamic World. In Europe, the horizontal axis wind machine became established about the 11th Century A.D., mostly having the form of a tower and rotating sails which became known as the Dutch windmill. The earliest recorded windmill dates from 1191 A.D. By the 18th Century A.D., multi-sail Dutch windmills were extensively used in Europe. It is estimated that by 1750 A.D. there were 8,000 windmills in operation in Holland and about 10,000 windmills in both Britain and Germany. Dutch settlers built windmills in North America, mainly along the eastern coast areas that became the New England states of the USA. At one stage, the shore of Manhattan Island was lined with windmills built by Dutch settlers.3

Fig. 1.4Classical ‘Dutch’ windmill in Southern England (unknown origin).

The principal features of the classical type ofDutch windmill are illustrated in Fig. 1.4. Usually there are four sails, located upstream (i.e., facing into the wind). Five, six and eight sail mills have been built. Although a five-sailed machine is relatively efficient, it is disabled by the failure of just one of its blades. On the other hand, a six-sailed machine can continue to operate with four, three or two sails, if necessary. One of the many engineering sketches left by Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519 A.D.) represents a design for a six-sailed windmill.4

To achieve variation of the rotational speed, the effective sail area of a Dutch type of windmill can be modified by the use of shutters. This corresponds to furling the sails on a yacht. Furling or shuttering can also be used to prevent over-speeding in high wind conditions. The cupola on top of the tower, in Fig. 1.4 for example, is designed to rotate, under the guidance of a rudder or stabilizer wheel, so that the sails remain upstream and perpendicular to the wind direction. Mechanical rotational power obtained from the sail shaft is transmitted down the tower, via a beveled toothed bearing, onto a vertical drive shaft. This, in turn, drives a toothed gear system which supplies power to rotate a grinding wheel for the corn.

In Fig. 1.4, the height of the horizontal, rotating axis above the ground is often called the “hub height”. For a typical windmill this might be 30 ft, 40 ft or even 50 ft high. Despite such a large structure the power rating of this Dutch type windmill is the mechanical equivalent of only a few tens of kilowatts. The power developed by such a large structure is therefore roughly equivalent to the electrical power supply now required by a large family house in Western Europe or North America. In engineering terms, the efficiency of a Dutch windmill is low, although this may be a secondary consideration since the input power is free.

Wind energy is transmitted by what is essentially a low density fluid. (i.e., the wind). The physical dimensions of any device used to convert its kinetic energy into a usable form are necessarily large in relation to the power produced. Wind availability is not only intermittent but unpredictable. The energy source, however, is free, environmentally clean and infinitely renewable. There is no pollution and no direct use of fossil fuels in the energy gathering process.

References

1.“Coriolis effect” National Geographic Education www.nationalgeographic.com/education/encyclopedia/coriolis-effect/?ar-a=1.htm June 2014.

2.“Wind Energy and Wind Power”, Solcomhouse website, Oct. 2008, http://www.solcomhouse.com/windpower.htm

3.McVeigh, J. C., Energy Around the World, Pergamon Press, Oxford, England, 1984.

4.Golding, E. W. The Generation of Electricity by Wind Power Chapter 2 “The History of Windmills”, E. and F. N. Spon Ltd., London, England, 1955.

![]()

CHAPTER 2

Theory of Wind Converters

2.1Power and Energy Basis of Wind Converters

2.1.1Origin and properties of the wind

From the viewpoint of energy conversio...