![]()

![]()

Chapter 1

Pages of Wolfgang Pauli’s Biography

Wolfgang Ernst Pauli was born in April 1900, Vienna to a chemist Wolfgang Joseph Pauli (né Wolf Pascheles) and his wife Bertha Camilla Schütz. Pauli’s middle name was given in honor of his godfather, physicist Ernst Mach. Pauli’s paternal grandparents were from prominent Jewish families of Prague; his great-grandfather was the Jewish and Hebrew publisher Wolf Pascheles, who was very well-known and highly esteemed in Central and Eastern Europe.

Pauli attended the Döblinger-Gymnasium in Vienna, graduating with honors in 1918. Two months after graduation, he published his first paper, on Albert Einstein’s theory of general relativity. Then he enrolled at the Ludwig-Maximilians University in Munich, where he received his PhD in 1921. His thesis adviser was Arnold Sommerfeld.

In 1923, Pauli was appointed a privatdozent at Hamburg University. Later he wrote [1]:

Very soon after my return to the University of Hamburg, in 1923, I gave my inaugural lecture as privatdozent on the periodic system of elements. The contents of the lecture appeared very unsatisfactory to me, since the problem of the closing of the electronic shells had not been clarified any further.

In 1924, working on a seemingly marginal problem, the anomalous Zeeman effect, he discovered the Ausschliessungsprinzip – Pauli’s exclusion principle – which earned him the 1945 Nobel Prize in Physics. The year of 1927 was dominated by an intense discussion between Werner Heisenberg, Niels Bohr, Pascual Jordan and Wolfgang Pauli on the Lösung des Quantenrätsels (solution of the quantum enigma), as Pauli called it in a letter to Bohr. In his recollections Pauli returns to Hamburg more than once. For instance [2],

The three days of November 29, 30 and December 1 [1955] I spent in Hamburg where I had not been for a long time. There I gave a lecture by invitation, and in one newspaper my name and the hotel in which I stayed were mentioned. This gave rise to a romantic adventure: a woman whom I knew 30 years ago announced herself. I had completely lost sight of her. As a young girl she had become addicted to morphine and I considered her lost. She phoned me on November 29 at about 5 p.m., and I saw her on December 1 for two hours before I got on the fast sleeping-car train to Zurich. An entire human life of 30 years passed by before me during these two hours; of her cure, a marriage and a divorce, with war and national socialism as historical background.

It was in 1927 in Hamburg that the first encounter of Wolfgang Pauli and Charlotte Houtermans occurred. In her “Last Diary” Charlotte writes (see [3], p 333.):

At a meeting in Hamburg in the early part of 1927 I met practically all the Göttinger physics community: Walter Elsasser, Fisl, Dirac, Oppenheimer, Condon, Pauli, Thorfin Hogness, Wiersma1 and many more.

The year 1927 was also marked by a personal tragedy for Pauli: his mother, to whom he had been very close, committed suicide after learning about an affair Pauli’s father was having. In the following year his father remarried making Pauli even unhappier. Pauli referred to his father’s new wife as “the evil step-mother.” On May 6, 1929, Pauli left the Roman Catholic Church. Further unhappiness was to follow when he married Käthe Margarethe Deppner, a cabaret dancer, in Berlin on December 23, 1929. This marriage was rather disastrous and ended in divorce in Vienna on November 29, 1930.

In 1928 the Swiss Board of Education appointed Pauli as Debye’s successor at the Eidgenössische Technische Hochschule (ETH) – Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich. On August 29, 1928, he assumed the position of the Professor of Theoretical Physics. These were fruitful years for Pauli. On December 4, 1930, he wrote in a letter to Lise Meitner that “the continuous β-spectrum would be understandable under the assumption that during β-decay a neutron is emitted along with the electron.” A new particle which Pauli called “neutron” is now known as neutrino, following Fermi’s suggestion (1933).

Pauli and Einstein (courtesy of Pauli Archive at CERN).

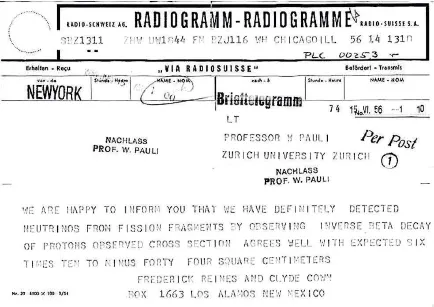

The public announcement of Pauli’s prediction came at a conference in Pasadena, California, on June 16, 1931. The New York Times on June 17 reported: “A new inhabitant of the heart of the atom was introduced to the world of physics today when Dr. W. Pauli of the Institute of Technology in Zurich, Switzerland, postulated the existence of particles or entities which he christened ‘neutrons’.” Pauli said about his discovery [4]: “I have done a terrible thing, I have postulated a particle that cannot be detected.” And, indeed, direct experimental observation of neutrino did not occur until 25 years later: in 1956 Clyde Cowan and Fred Reines at Los Alamos detected it in a nuclear reactor experiment. Of course, nowadays this is not unprecedented; physicists are accustomed to even longer waits. For instance, fifty years elapsed between the prediction of the Higgs boson and its detection...

Telegram from Frederick Reines and Clyde L. Cowan to W. Pauli received on June 15, 1956, informing Pauli of their neutrino discovery in nuclear fission. In 1995 the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics to Frederick Reines “for the detection of the neutrino.” Pauli’s reply to the telegram did not arrive, but it survived in the form of a draft: “Thanks for message. Everything comes to him who knows how to wait. Pauli.” From https://timeline.web.cern.ch/neutrinos-detected-at-last.

Approximately at the same time, in 1928-1930, Pauli (in collaboration with Werner Heisenberg) wrote two papers which played a crucial role in creation of quantum field theory [5].

On April 4, 1934, Pauli married Franciska (Franca) Bertram. This was a happy marriage. After Pauli’s death, Franca Pauli said this of her late husband: “He was very easily hurt and therefore would let down a curtain. He tried to live without admitting reality. And his unworldliness stemmed precisely from his belief that this was possible.”

Pauli on his way to Pasadena to announce his prediction of neutrinos, 1931 (courtesy of Pauli Archive at CERN).

In 1933, after Hitler came to power in Germany, Viki Weisskopf emigrated from Germany to Switzerland and shortly after became Pauli’s assistant. Much later Weisskopf wrote in his memoir [6]:

Finally, Pauli lifted his head and said: “Who are you?”

I answered: “I am Weisskopf, you asked me to be your assistant.” He replied: “Oh, yes, I really wanted Bethe, but he works on solid-state theory, which I don’t like, although I started it.”

The regular duties of Pauli’s assistants were minor, as Weisskopf observed in his recollections [6],

My main duties were to be ready for discussions of his work and to assist him in any new developments. However, I once actually became his accomplice. His wife [Franca] had asked him to change his eating habits in an attempt at reducing his famous girth. But Pauli loved sweets of all kinds, and many afternoons he would want to continue our discussions in a nearby Konditorei (café) that had wonderful pastries. I had to promise never to mention these clandestine outings to Mrs. Pauli.

Peter Freund presents us [7] a precious gift, a sketch of Pauli the seminar leader:

[Pauli] would go to seminars and like a davening Jew rhythmically nod his approval of everything the speaker was saying, until that moment came, as it almost always did, when the speaker said something Pauli disagreed with, at which point intense shaking of his head replaced the nodding and most speakers fell apart. Vicki Weisskopf, Pauli’s assistant in the mid-1930s, devised a strategy to cope with Pauli’s nodding-to-shaking transition. On the morning of the day he was scheduled to give a talk, he would go to Pauli’s office and give Pauli a preview. Pauli would tell him it was sheer madness and would forcefully try to talk him out of it. Then at the seminar when the “dangerous stuff” came, instead of shaking his head, Pauli would continue to nod while every now and then muttering to himself, “I told him this is madness.” Apparently, though successful, Weisskopf’s strategy was not widely known. It is said that upon his death in 1958, Pauli arrived in heaven and was summoned to God’s office. Pauli asked God how it all works, and God went to the heavenly blackboard and started giving Pauli a private lecture. Pauli nodded at the beginning, but some twenty minutes into the talk he started shaking his head. Completely unnerved, God imprudently mentioned this to a few of the archangels, who spread it throughout the heavens causing universal heavenly consternation. Ultimately this was even leaked to earth by some lesser angel no doubt – that’s how even I heard of it.

Someone who was this merciless with his younger and older colleagues and even with the very highest authority could not be expected to be much easier going when it came to students. A student at Cambridge, Homi J. Bhabha, who later became one of the first internationally recognized Indian theoretical physicists, was sent by his adviser to work with Pauli in Zurich. The introduction letter said, “Pauli, you are the only one who can possibly make a physicist out of Mr. Bhabha” – hardly a very flattering thing to say. Pauli, who respected the author of this letter, interpreted it to mean that this was a hopeless case. Accordingly, he refused to have any meaningful talk with Bhabha, convinced that it would be a total waste of time. Whenever he noticed Bhabha in the hall, he would shout at him past the many other students hurrying to their classes, “Mr. Bhabha, what nonsense are we working on today?” The young man was despondent. It is, however, in Zurich that he wrote his most famous paper on electron–positron scattering, or “Bhabha scattering” as it is now called. When he tried to show the paper to the great man, Pauli responded, “If you did this, I am not interested.”

Another episode worth mentioning was narrated by Elsasser [8]:

I lived in Paris and was writing many scientific papers. Usually, I thought they were tolerably good, but once I slipped: I concocted some bad piece of nonsense. Promptly, about two or three weeks after my little note had appeared in print, I received a brief letter from Pauli. It said that if I ever published any similar goddamn nonsense again, he would withdraw his good-will from me.

This implied that Pauli not only took notice of any piece of new literature in the field of atomic theory, but actually read everything critically. He corresponded whenever he thought his comments would do some good. His note to me being only one very small example; and I believe that in this resided a large part of his importance for modern physics, quite apart from his own monumental contributions.

What a nostalgic passage about genuinely serious attitude to physics, now long gone ...

During the winter term of 1935/36 Pauli received his first invitation to the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, NJ, (then called the Flexner Institute). This private research center had been founded in 1930 with an initial donation of five million dollars2 by the American merchant Louis Bamberger. In April 1936 Pauli wrote from Princeton to Weisskopf (who was still in Zurich):

I have received your letter and have gladly taken notice that you consider my influence on you not at all as so injurious...

On April 18 the boat leaves New York. On 26 we arrive in [Le] Havre, and then I will drive my new American car to Zurich.

In 1938 Germany annexed Austria, and Wolfgang Pauli’s Austrian citizenship was converted into German.

This created a serious problem for him. Under the Nazi racial theory Pauli was 75 percent Jewish. As well as his father being Jewish, his mother’s father was too. If the Germans were to occupy Switzerland his passport would receive the dreaded “J” stamp [i.e. Jewish], which would mean almost certain death. The subsequent events are described in [9; 10], from which I quote.3

He immediately applied for Swiss citizenship but his application was refused. The...