![]()

1

Through the Eye of the Needle — The Story of the Soil Microbial Biomass

David Powlson*,‡, Jianming Xu† and Philip Brookes*,†

*Department of Sustainable Soils and Grassland Systems,

Rothamsted Research, Harpenden, Herts., AL5 2JQ, UK

†College of Environmental and Resource Science,

Institute of Soil and Water Resources and Environmental Sciences,

Zhejiang University, Hangzhou 310058, China

Birth of the Microbial Biomass Concept

In 1966, David Jenkinson at Rothamsted Research, UK, published a paper that led to a new paradigm in soil science, despite its innocuous sounding title “Studies on the decomposition of plant material in soil. II. Partial sterilisation of soil and the soil microbial biomass.” We think that this was the first time that the term soil microbial biomass appeared in the scientific literature; it refers to the total mass of all organisms in soil. David Jenkinson later described the microbial biomass as the “eye of the needle through which all organic matter entering the soil must pass”. Ten years later, the concept was reinforced and a specific method for measuring the quantity of carbon (C) held in the soil microbial biomass was published in a series of papers by David Jenkinson, David Powlson and others that have been very widely cited (Jenkinson, 1976; Jenkinson and Powlson, 1976a, b; Jenkinson et al., 1976; Powlson and Jenkinson, 1976). The method proposed in 1976 became known as the chloroform (CHCl3) fumigation–incubation method, later abbreviated to FI to distinguish it from the CHCl3 fumigation–extraction method, developed later and termed FE (Vance et al., 1987b). Much of the 1976 research resulted from the Ph.D. work of David Powlson carried out under the supervision of David Jenkinson. Later developments including the development of the FE method for measuring biomass C and methods for measuring N and P in the biomass were largely led by Phil Brookes.

For post-millennial soil researchers, those beginning their work after or around the year 2000, it may be difficult to understand the scientific context of soil microbiology in the 1960s. The genetics revolution had barely started — Watson and Crick had published their discovery of the structure of DNA only 13 years before the Jenkinson (1966) paper. Molecular biological concepts and methods that are now routine were unheard of. The concept of measuring the properties of an entire population, such as the quantity of C held in all living organisms in soil, was not common. At that time, the major focus of soil microbiology was the identification of organisms responsible for specific processes. Processes of interest included ammonium oxidation (nitrification), cellulose decomposition and the degradation of individual pesticides.

By far the major tool available for studying soil microorganisms was culturing under laboratory conditions using agar plates containing different nutrients to give some specificity to the species of organisms likely to grow. Population sizes were assessed by an extension of this approach based on counting the number of colonies developing on plates of nutrient agar from increasingly diluted soil extracts; the method was termed “plate counting”.

While many soil microbiologists recognised the limitations of this approach for quantitative studies, little else was available. The concentration of nutrients used for plate counts was usually far greater than likely to be present in soil, thus calling into question the relevance of many findings on population sizes and trends. Despite all this, the approaches used at that time were not without success. For example, in 1952, Selman Waksman at Rutgers University, USA, was awarded the Nobel Prize for medicine in recognition of his discovery of antibiotics produced by organisms in soil. At Rothamsted, UK, Norman Walker discovered a new class of soil bacteria responsible for nitrification in soil: Nitrospira to be added to the better known Nitrobacter and Nitrosomonas species.

By the 1960s, it was becoming clear that the majority of bacteria and fungi in soil did not grow under the laboratory conditions normally used — the term “viable but unculturable” began to be used. This recognition arose due to the so-called direct counting of soil microbes when it was found that the number of organisms observed when soils were examined under the microscope was many times greater than numbers based on plate counts (Skinner et al., 1952). One direct counting technique, not relying on the growth of colonies on nutrient agar, was a method developed by Jones and Mollison (1948) and often called the Jones–Mollison agar film technique. In this method, a known mass of soil is dispersed in a known volume of warm liquid agar and small volumes taken and allowed to solidify as thin films in a haemocytometer slide of known depth. Agar is used not as a source of nutrients but simply as a means of converting a liquid dispersion to a solid film that can be observed under a microscope. The solidified agar film is transferred from the haemocytometer to a microscope slide, stained with an appropriate stain that is reasonably specific to living organisms as opposed to dead organic particles, and the number of stained organisms counted under a microscope. We return to this method later in the chapter.

So far as we can tell, 50 years after the event, David Jenkinson did not initially set out to develop a method for measuring the quantity of organic C held in the soil microbial population. He had entered the world of soil science from a background of a Ph.D. in organic chemistry and initially applied the methods of organic analysis to studying the chemical composition of soil organic matter (SOM). But he rapidly concluded that SOM was such a complex mixture that the chemical analytical methods available at the time were incapable of yielding much useful information, so he turned his attention to the dynamics of SOM rather than its chemical structure. He and others realised that freshly formed SOM, derived from recent inputs of plant material, behaved differently to native SOM, much of which exhibited great stability and resistance to microbial decomposition.

Jenkinson was amongst the first to apply isotopic methods to distinguish between recently derived C and native C in soil. He did this by growing ryegrass in an atmosphere labelled with 14CO2 and then adding the 14C-labelled plant material to soil under field conditions for up to 4 years. In an earlier paper Jenkinson (1965) had shown that the labelled grass initially decomposed rapidly — about two-thirds of the added C was evolved as CO2 within 6 months in the temperate climate of Rothamsted, but thereafter decomposition was far slower with about one-fifth of the labelled C remaining in soil after 4 years. This was a strong indication that SOM could be regarded as existing in pools or fractions that differed greatly in their rates of turnover. We consider that this was one powerful strand of reasoning that led Jenkinson to the concept of the microbial biomass as a discrete and meaningful fraction within soil.

Simultaneously, there was interest in the idea of different rates of turnover of SOM in different fractions from a more practical viewpoint, namely the supply of nitrogen (N) from soil to crops. SOM in agricultural soils typically contains several thousand kg ha−1 of N in organic forms, yet only a few percent of this is converted into inorganic forms and thus available for plant uptake each year, typically around 20–200 kg N ha−1. During the 1960s, and still today, there is interest in better predicting the N supply from SOM during a given crop-growing season so that fertiliser applications can be adjusted accordingly. Jenkinson was involved in such work around this time and published a method for predicting N mineralisation based on the extractability of specific forms of organic C from soil using dilute barium hydroxide solution (Jenkinson, 1968).

A third strand of reasoning that certainly had a major influence on his thinking was ongoing research at the time by plant pathologists at Rothamsted and worldwide experimenting with soil fumigants to control soil-born plant fungal diseases and parasitic nematodes. The chemicals used were typically broad-spectrum biocides designed to kill virtually all soil organisms; they included formaldehyde, methyl bromide, trichloro(nitro)methane (known as chloropicrin) and other halogenated hydrocarbons. It was frequently observed in such studies that, even in soils with no apparent pest or disease problem, plant growth was stimulated; in many cases this was attributed to additional mineralisation of N compared to unfumigated soil, though other factors were also thought to be involved as discussed by Jenkinson (1966) and Powlson (1975). The source of this additional N was a matter of interest and, as a key aspect of fumigation was killing of organisms, decomposition of the killed soil microbial cells was considered a likely source. It seemed likely that a recolonising population of microorganisms in the soil would utilise the cells of killed organisms as food with the N in organic forms being mineralised and released as inorganic N. This would also account for the period of enhanced soil respiration observed following soil fumigation, measured as enhanced evolution of CO2 and uptake of oxygen. This line of reasoning appears to have been the breakthrough in Jenkinson’s thinking that led to the idea of a way of measuring the quantity of C held in organisms before being killed by the fumigant. It is interesting that this “eureka moment” came through cross-fertilisation between scientists working in different fields — SOM studies and plant pathology. It is a reminder that all scientists can benefit from hearing about ideas in other fields — something about which Jenkinson was particularly enthusiastic.

Establishing the Chloroform Fumigation–Incubation (FI) Method

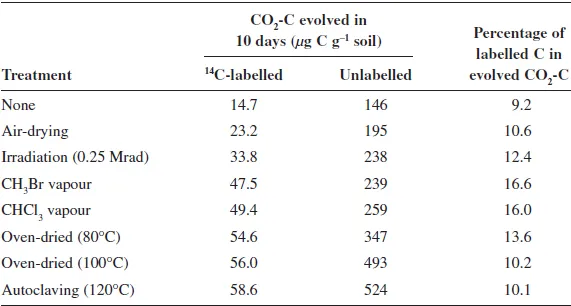

14C-labelled C in the soil amounted to only 1.8% of the total soil organic C, yet the CO2-C evolved from untreated soil when incubated in the laboratory for 10 days at 25°C was more than five times as enriched (Table 1.1). This indicated that C involved in biological processes leading to CO2 evolution was far more heavily labelled with 14C than the soil organic C as a whole. All of the treatments tested increased total CO2 evolution but, importantly, several of them greatly increased the percentage of labelled C in the CO2 evolved. Fumigation with chloroform or methyl bromide (CH3Br) almost doubled this proportion to around 16% (Table 1.1). Jenkinson reasoned that the C in cells of microorganisms (the soil microbial biomass) was likely to be the most heavily labelled organic C fraction in the soil, so a treatment giving the greatest increase in 14C labelling of evolved CO2 must be selectively acting on this fraction. Because CHCl3 was easier to use than CH3Br and was thought to be less toxic to humans, Jenkinson used CHCl3 fumigation for further work. Although oven-drying and autoclaving increased evolution of labelled CO2 by a similar amount to fumigation, they also increased evolution of unlabelled CO2 considerably. Jenkinson interpreted this to mean that these treatments, in addition to killing organisms, also rendered additional non-biomass (and more lightly labelled) forms of organic C decomposable and thus were less selective.

Table 1.1Labelled and unlabelled CO2 evolved by soil exposed to partial or complete sterilisation treatments, inoculated with fresh soil and incubated for 10 days at 25°C.

Note: The soil had previously been incubated with labelled plant material for 1 year under field conditions.

Source: Adapted from Jenkinson (1966).

An important conclusion from the results with labelled soil was that CHCl3 had very little effect on the rate of decomposition of non-biomass organic C in soil. Following this conclusion, and several other simplifying assumptions, Jenkinson set out the following expression for estimating the quantity of C in soil microbial biomass (BC) as follows:

where Fc is the flush of decomposition following chloroform fumigation defined as (CO2-C evo...