![]()

Chapter 1

How Do Human Resource Practices Strengthen Open Innovation? An Exploratory Analysis

Svenja Paul

Philips Electronics

Nadine Roijakkers

Hasselt University

Letizia Mortara

University of Cambridge

How do human resource practices strengthen open innovation (OI) activities? This inductive study of six cases leads to propositions exploring this question, which has not been empirically investigated yet. We investigate the relation between human resource practices and an employee’s willingness to embrace OI in six cases that include the perspectives of chief executive officers (CEOs), human resource managers, and experts from Belgium, the Netherlands, and the United Kingdom regarding human resource practices in both small and large companies actively pursuing OI. The findings reveal that when implementing OI, it is people’s thinking and attitudes towards this approach to innovation that can strengthen OI activities. Human resource practices can influence peoples’ behaviours and attitudes towards OI by strategically selecting candidates, by rewarding employees, and by establishing a strategically focused climate in which employees are stimulated and feel comfortable being open, talking to others about their ideas, etc. Training practices were found to be negligible. The findings further reveal a number of human resource challenges that need to be overcome when organizing for OI.

1. Introduction

This chapter studies the role of human resource practices in stimulating open innovation (OI) activities. Ever since Chesbrough coined the term “Open Innovation” in 2003, numerous contributions have arisen studying the ways in which companies open up their innovation activities to take advantage of the abundant knowledge landscape outside their boundaries (Chesbrough, 2003). Despite the abundant research attention for OI related topics, little progress has been made in the area of the internal organization and management of OI (Vanhaverbeke and Roijakkers, 2012). Of particular interest is the role of human resource management in OI. Golightly et al. (2012) have found that OI is a people-driven process, concluding that individuals should be the focus of attention when implementing this particular approach to innovation. They point out that there is considerable potential for further research into the people side of OI, including organizational development, HR practices, and performance management. From a practitioner’s perspective, Goers (2011) states that for institutionalizing OI at Kraft Foods, developing effective tools, processes, and operating models is not sufficient. More than that, employees’ behaviours need to be addressed and a culture focused on OI needs to be built where all employees “live” the OI mindset. Likewise, Martino and Bartolone (2011), based on their experiences at Unilever, emphasize that ultimately OI is about people, relationships, and trust. One of the first studies to empirically investigate the people side of OI is the dissertation on innovation cultures by Herzog (2011). His study provides evidence of cultural differences between open and closed innovation units where employees’ personalities were studied and compared. He argues that in terms of personalities, being proactive, creative, and result-oriented is more relevant in OI settings than in closed innovation units. Furthermore, Du Chatenier et al. (2010), in their study on competencies for professionals in OI teams, have found that the three most important competencies that individuals within these teams need to possess are combinatory skills, social astuteness, and sociability. Despite this thin body of (mainly practitioner-oriented) research, a significant knowledge gap remains regarding the role of human resource practices, such as selection, training, and rewarding, in supporting OI activities. To the best of our knowledge, this is one of the first studies to empirically investigate human resource management in relation to OI.

Since empirical evidence concerning the role of human resource management in OI is scarce, the current study is of an exploratory nature, seeking to gain insights and to generate ideas regarding human resources practices in different types of OI settings. The aim is to build a theory based on cases, a method described by Eisenhardt (1989). To this end, we examine six case studies, including the perspectives of chief executive officers (CEOs), human resource managers, and experts from Belgium, the Netherlands, and the United Kingdom regarding human resource practices in both small and large companies actively pursuing OI. The diversity of cases allows for rich insights into the topic under investigation, bringing together various perspectives from different countries, industries, and firm sizes. Data were mainly collected through semi-structured, in-depth interviews.

The chapter is structured as follows. First, in Section 2, we review the scarce literature that is available on the topic while focusing both on the human resource management literature as well as contributions to the OI literature. In Section 3, the research methodology is described. Subsequently, the results of the case analyses are presented in Section 4. Section 5 concludes with a discussion of the findings as well as important implications for both managers and academics.

2. Theoretical Background

While there are ample OI studies, only few researchers so far have paid attention to the premises underlying the effective internal organization and management of OI. Based on a study regarding the realization of value from OI, Golightly et al. (2012) have identified a number of building blocks that need to be considered when organizing for OI: OI strategy, organization, leadership, culture, tools/ processes, metrics, ecosystem interaction, skills, and business models/ intellectual property. They conclude that when developing OI, organizations need to “(…) focus first on getting individuals to realise the potential value of OI, so that they can then put in place practices that realise its actual value” (Golightly et al., 2012, p. 62).

While it is important to get the technical part right, the quality of people’s thinking as they engage in this process will effectively make it work as they change their thinking, for example, from a “not-invented-here” mindset to a “proudly-found-elsewhere” attitude (Huston and Sakkab, 2007). Employees need to become open with regards to external ideas and recognize the benefits from OI. Especially in large organizations, this mindset change presents one of the biggest challenges when organizing for OI (Mortara et al., 2009). Because human resource practices are seen as the primary means by which organizations can influence and shape the attributes and behaviours of employees in terms of a particular strategy (Wright and McMahan, 1992; Chen and Huang, 2009), it can be a valuable tool for strengthening OI activities.

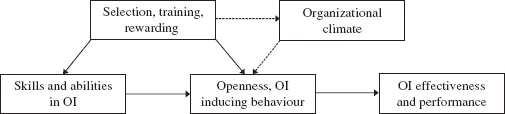

According to Brockbank (1999), human resource practices can be divided into four broad categories, being either operational or strategic in nature. At the operational level, these practices include operationally reactive human resource activities, which focus on implementing human resource basics, and operationally proactive human resource activities, which seek to improve these human resource basics. From a strategic perspective, they include strategically reactive human resource activities, which support the implementation of a given business strategy by giving tactical support and by establishing a strategically focused culture, and strategically proactive human resource activities, which focus on creating future strategic alternatives. Seeing OI as (part of) a given business strategy, the focus of this chapter is on strategic human resource practices. Strategic human resource management is defined as “the pattern of planned human resource deployments and activities intended to enable an organization to achieve its goals” (Wright and McMahan, 1992, p. 298). In this respect, human resource practices can be described as tools that are used to manage the skills, abilities, and behaviours of employees, whereby the skills and abilities affect the behaviours of employees, which in turn have a direct effect on firm-level outcomes (Wright and McMahan, 1992). While these relations have not been empirically investigated within an OI context yet, several scholars have investigated the relationship between the adoption of human resource practices and general innovation performance (Ceylan, 2013; Chen and Huang, 2009) and knowledge sharing (Cabrera and Cabrera, 2005; Collins and Smith, 2006). Ceylan (2013) has explored the relationship between a commitment-based human resource system, which is a bundle of commitment-oriented human resource practices, and product innovation activities. The items in the commitment-based human resource system include selection, incentives, and training and development. The findings show that a commitment-based human resource system has a positive effect on process, organizational and marketing innovation activities, which in turn relate positively to product innovation activities. In investigating the effects of strategic human resource practices on knowledge management capacity, Chen and Huang (2009) include staffing, training, participation, performance appraisal, and compensation. They have found a positive effect on knowledge management capacity, which in turn relates positively to innovation performance. Cabrera and Cabrera (2005) have identified specific human resource practices that facilitate and encourage knowledge sharing. They have done so along the following seven categories: Work design, staffing, training and development, performance appraisal, compensation and rewards, culture, and technology. Examples include the creation of cross-functional teams, hiring of people for whom they are, not for what they can do, making knowledge-sharing criteria critical for one’s career success, and creating a caring and fair culture. Collins and Smith (2006) have investigated the link between human resource practices, knowledge exchange and combination, and firm performance. They demonstrate that human resource practices affect the organizational social climate of trust, cooperation, and shared codes and languages, which in turn facilitates knowledge exchange. In Cabrera et al. (2006) study on the determinants of individual engagement in knowledge sharing, the authors have found that besides system-related variables, organizational and psychological variables predict the engagement level. For the latter, self-efficacy and openness to experience were the strongest predictors for engagement level. Among the organizational variables, perceived support from top management and co-workers significantly predicted engagement level, while rewards had a moderate direct effect on knowledge sharing. The authors go on by discussing that these findings may have implications for human resource practices such as screening, training, and rewarding employees. In this sense, they suggest that an organization that seeks to foster knowledge sharing may screen candidates for having a high cognitive aptitude, being intrinsically motivated, and open to experience. The reviewed studies suggest that there is a positive relationship between human resource practices and innovative performance. Furthermore, the organizational climate is, among other things, demonstrated to be a mediator between human resource practices and employees’ behaviours in terms of knowledge sharing and innovative performance. Likewise, in the OI literature, Wallin and von Krogh (2010) have found a cooperative and positive organizational climate with shared values, norms, and attitudes to be supportive when organizing for OI. For establishing a framework relating human resource practices to OI, we propose to adapt the conceptual model that is used for studying strategic human resource management, as depicted in Fig. 1 and further described below.

Fig 1. Towards a framework relating strategic human resource practices to OI

Source: Adapted from Wright and McMahan (1992, p. 299)

Specific human resource practices differ across companies and studies, but they generally include selection, compensation, and training and development practices (Collins and Smith, 2006). From practical examples, it can be derived that these three human resource practices are also relevant when it comes to OI. Regarding selection, one of the main principles of OI in contrast to closed innovation is the realization that not all the smart people work for one’s company (Chesbrough, 2003). Vanhaverbeke, in an interview with Starckx (2011), describes that within the process of OI, the traditional human resource department needs to become a “scouting division”, not only looking for and hiring the best internal people, but going one step further by identifying the best people outside the company and cooperating with them. Kelley (2012) describes the process of attracting and managing talent outside the company as an “external talent strategy”, whereby organizations move from a “talent ownership” mindset to a “talent attraction” mindset. A similar theory is that of the “long tail of expertise” explained by Bingham and Spradlin (2011). They put forward that besides hiring experts with the right skills to solve an immediate problem, human resource managers should also find ways of engaging experts from the outside who can work for the company without being employed by it, and tapping into “the long tail”, consisting of all the smart people outside the company who can jointly solve any kind of problem that might arise in the future (Bingham and Spradlin, 2011). There is a link between the selection and training of people, as required attributes can either be found on the outside, or be trained on the inside. If people need the right attributes to flourish in OI, then these could probably be learned.

However, among psychologists, openness is seen as a personality trait (Digman, 1990). More important than possessing the right attributes may thus be having the right personality, which is generally viewed as more difficult to train. Rewarding practices may be challenging in OI. Several managers have stated in interviews that it is essential to recognize openness to external ideas formally and informally, and to include it in evaluation and reward structures (e.g. Thoen, 2009; Byrum, 2012). Ultimately, people need to be moved when knowledge shall be moved (Chesbrough, 2003). This can influence rewarding practices as, for example, the pension scheme is given up when leaving a large company for a newly founded one.

Human resource skills and abilities, the next element in the model, are seen as one of the main issues that companies have to tackle when implementing OI, as the knowledge of the company and the right blend of skills of individuals can act as an OI enabler, while the lack of appropriate skills can act as an obstacle to OI (Mortara et al., 2009). With the implementation of OI, traditional scientists need to take on a new role, integrating scientific knowledge, managerial expertise, and commu...