![]()

Chapter 1

Singapore’s Education in World Rankings: School and Higher Education and Beyond

Globalization not only brings about international cooperation but also international competition. Nations make their best efforts to be seen as welcoming international collaborations and project an image of capability in joint endeavors, especially through showing the availability of educated human capital (Stewart, 2012; Hazelkorn, 2015). Although globalization may not be the original motivation for international rankings of education, it definitely has contributed to the popularity.

World rankings of school education started with the appearance in 1999 of the Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS) of the International Association of Evaluation of Educational Achievement (IEA), followed in 2000 by the Progress in International Reading Literacy Study (PIRLS) (PIRLS and TIMSS International Centre, 2016). In 2000, the Programme for International Students Assessment (PISA; OECD, n.d.) of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) emerged with a presumably different conceptual framework, though not a different methodology.

It is a well-established fact that some East Asian countries consistently top the lists of world rankings on school education; these include Shanghai-China, Hong Kong-China, Japan, Korea, Singapore, and Taiwan. There have been research efforts to identify the reasons for this phenomenon. In a recent article, Jerrim (2014) cites reasons advanced by previous studies and includes teacher selection and quality, teaching methods, work ethics, ‘tiger’ parenting, extensive out-of-school tuition, genetics/natural ability, the value East Asian families place upon education, the design of the school curriculum, and even foul play. Obviously, education is multi-faceted and the East Asian success can be attributed to many and varied reasons and the list goes on.

Jerrim’s (2014) own study involved a very large sample (N = 14,481) of students in Australia, including second-generation East Asian immigrants from Hong Kong, Japan, Singapore, China, Korea, and Taiwan. When compared with native Australian students, the East Asian immigrants had an average of 600, which is one full standard deviation (SD) above the Programme for International Students Assessment (PISA) mean of 500. They had six more hours weekly of after-school tuition and scored higher (by at least effect size of 0.2 or thereabouts) for work ethics, internality, subjective norm, and instrumental value. And, 36 percent more expected to go to university. Moreover, these students were particularly strong in mathematics. The author concluded:

… I find little evidence that a single factor can explain the exceptionally strong PISA performance of this group. Rather a combination of school selection, a high value placed upon education, substantial out-of-school tuition, hard work ethics, a belief that anyone can succeed with effort and high aspirations for the future, all play an important, inter-linked role.

Besides world rankings on school education, there has been a keen interest in rankings of higher education. World rankings of higher education started in 2003 with the Academic Ranking of World Universities (ARWU) at the Shanghai Jiaotong University. This was soon followed in 2005 by the Quacquarelli Symonds and Times Higher Education World University Rankings (QS–THEWUR). This was a joint effort of the London-based consultancy and the Times Higher Education Supplement. In 2009, the two partners published separate rankings as Quacquarelli Symonds World University Rankings (QSWUR) and Times Higher Education World University Rankings (THEWUR). Although new ranking systems of higher education emerged in the subsequent years and now there are no less than 10 different systems, each claiming to have some strengths over the others, ARWU, QSWUR, and THEWUR are considered the three ‘classics’ (Hazelkorn, 2015).

There is no dearth of criticisms of these rankings on conceptual and methodological grounds (e.g., Soh, 2013). Nevertheless, such rankings may perform at least two useful information functions. Firstly, they enable nations to evaluate their efforts and achievements in the broadest context on earth and to plan for further development; this helps in identifying strengths and areas for improvement (AFI) for strategic planning. Secondly, the competitiveness inherent in rankings provides an impetus for continuous improvement and thus has a motivational function.

Take PISA as an example, after a brief review of controversy around PISA, Chalabi (2013) summed up the situation, thus:

… the academic community seems split between those concerned that national education policy is being dictated by an OECD statistical release with little public input and those who argue instead that politicians will always be guided by what is financially possible and politically popular, Pisa or no Pisa.

Perhaps, the most vocal collective criticism against PISA is the one made in an open letter signed by over 100 academics and administrators around the world to Dr. Schleicher, Director of PISA, calling for its suspension. After highlighting the concerns on the PISA methodology and impact, they suggested some remedies, but expressed their grave apprehension thus:

We assume that OECD’s Pisa experts are motivated by a sincere desire to improve education. But we fail to understand how your organization has become the global arbiter of the means and ends of education around the world. OECD’s narrow focus on standardized testing risks turning learning into drudgery and killing the joy of learning. As Pisa has led many governments into an international competition for higher test scores, OECD has assumed the power to shape education policy around the world, with no debate about the necessity or limitations of OECD’s goals. We are deeply concerned that measuring a great diversity of educational traditions and cultures using a single, narrow, biased yardstick could, in the end, do irreparable harm to our schools and our students.

However, Takayama (2015) reviewed the debate and presented a more balanced view, pointing out the uncritical assumption of homogeneous impact around the globe and domination by scholars based in the United States (USA).

Needless to say, using the ranking results and relevant information for these two purposes, care needs be exercized to avoid misinterpretation or being misguided, with due caution against the criticism. With the above as back drop, this chapter lays out factually the rankings on school and higher education of Singapore for a comprehensive overview of what this pint-sized country have achieved in the past one-and-a-half decades in developing her human capital in the context of globalization.

School Education in Singapore

OECD first started the PISA in 2000. PISA is meant to evaluate education systems worldwide by testing the skills and knowledge of 15-year old students (OECD, n.d.).

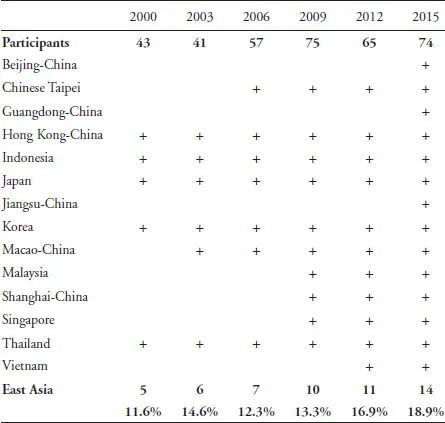

PISA is a triennial survey covering three core subjects of the school curriculum, namely Reading, Mathematics, and Science. Since its installation in 2000 with 43 participating countries, the number of participants has been on the increase.

As Table 1 shows, the participating countries increased from 43 in 2000 to 74 in 2015. Thus, over a 15-year period, the participation rate increased by 72 percent. This reflects the need for countries around the world to evaluate their students or education systems in the widest possible context through a common yardstick when the same assessment instruments are translated into languages of instruction. Here, the translated versions of the three subject tests are assumed to be equivalent and care has been taken to ensure a high degree of equivalence.

The number of East Asian countries participating in PISA increased from 5 (12%) to 14 (19%) over the 15-year period. Thus, the participation rate increased by 180 percent in one-and-a-half decades. This obviously reflects the keen interest of the East Asian countries in comparing themselves in the world’s competitive context, perhaps as a result of globalization when developing economies want to be seen as being actively engaging others and do not wish to be left out.

It is interesting to note that the People’s Republic of China (PRC) was originally represented by Hong Kong-China (starting in 2000) and Macao-China (joining in 2003) when these ex-colonies returned to China. Shanghai-China joined in 2009 and she will be joined in 2015 by one more Chinese city (Beijing) and two provinces (Guangdong and Jiangsu). For political reasons, Taiwan is labeled Chinese Taipei. Incidentally, these give rise to the question of how China is and should be represented. By the same token, a question can be asked whether, say, the USA should or should not be represented by cities and states likewise. The same question goes for the many large countries such as the United Kingdom (UK), France, Germany, etc. This is obviously a contention awaiting solution.

Table 1. East Asian Participating in PISA by Years.

Source: National Centre for Education Statistics. Available at https://nces.ed.gov/surveys.pisa/countries.asp

Singapore in PISA 2009: In the context of this chapter, it is of note that Singapore joined PISA only from 2009 onward and this means performance data are available only for the two surveys of 2009 and 2012 but not earlier.

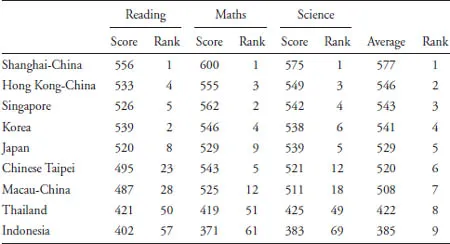

Table 2. East Asian Countries in PISA 2009.

Note: Ranks next to scores are original world rankings.

Table 2 shows the scores and rankings for Reading, Mathematics, and Science for the nine East Asian countries participated in PISA 2009. For this survey, there are 65 participating countries, with Singapore and Shanghai-China joining for the first time.

For the three subjects, five of the nine East Asian countries consistently have rankings within the top-10 among the 65 participating countries of the world. They are Shanghai-China, Hong-Kong-China, Singapore, Korea, and Japan. These are joined by Chinese Taipei in Mathematics. Thus, it is safe to conclude that the East Asian countries dominate the high rankings of PISA 2009.

It is interesting that the three subject scores for the 65 countries have very high correlations: Reading and Mathematics r = 0.96, Reading and Science r = 0.98, and Mathematics and Science r = 0.97. With such high intersubject correlations, it is justified that the average of the three subject scores is a good representation of the general performance.

With reference to averages thus derived, the nine East Asian countries were ranked. It is noted that Shanghai-China and Hong Kong-China occupy the first two positions and Singapore comes in third in PISA 2009 among the nine East Asian countries.

PISA scaled its test scores to have an international mean of 500 with an SD of 100. With reference to this standardization, it is of note that the means for the averages of Shanghai-China, Hong Kong-China, Singapore, and Korea are at least four-tenths of an SD above the international mean. Assuming normal distribution, the SD set the four countries far apart from the rest of the other participating countries with a difference of at least 16th percentile.

Singapore’s average of 543 indicates that she is almost half an SD (100) above the PISA mean of 500. And, for this, she has a 67th percentile, i.e., 17 percentile...