![]()

Chapter 1

A Brief History of Computing

Since the dawn of civilization, humans have been developing increasingly sophisticated methods of calculation and computation. The transition from simple, numerical systems to fully electronic machines takes us through a fascinating journey of knowledge and discovery in history. The design and construction of computing devices used today differ substantially from former models, and here, we will explore the progression of innovation within this complex field.

1.1From Numbers to Calculating

Numbers and their properties have remained my fascination ever since my early school years. What really intrigued me the most was how new kinds of numbers have been introduced to deal with problems. I learned that negative numbers were introduced to solve problems like this equation, 4 = 4 · x + 20, irrational numbers (i.e., numbers that cannot be expressed as fractions) are the solutions of equations like x2 − 2 = 0, and imaginary numbers (i.e., numbers that are multiples of i, the imaginary unit, a number whose square, i · i, is equal to −1) were devised to solve equations like x2 + 4 = 0. Although I learned many things about numbers and the problems they solved, still I had no idea who invented numbers and how people started using numbers. It seems there are no records that can be used to tell the history of the invention of numbers. So let us assume that there was a time when humans did not know how to count. At that time, they only used concepts like single, pair, and many when talking about quantities. In fact, nouns in ancient European languages had three numbers, that is, singular, dual, and plural. It is quite possible that they started to feel the need for counting when they began to domesticate wild animals. Shepherds needed to know how many animals were in their flocks so they had to know their exact number. These shepherds soon realized that a flock of six sheep and a flock of six goats have something in common: the quantity of animals is the same. Farmers realized the same when they counted fruits, vegetables, and so on. The conclusion was that it does not matter what one counts, but how many objects one counts. This simple remark is the essence of mathematical abstraction. And I suppose the first human being who realized this simple fact is probably the father of mathematics.

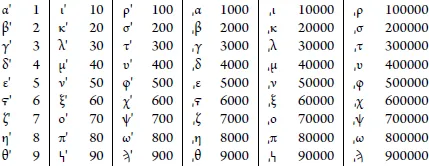

It is more than clear that early humans have used their hands as an aid to counting and calculation. Since our hands have 10 fingers, humans in most parts of the planet have used this number as a basis for counting. In other words, the decimal numeral system that we use today was invented by the first people who used their fingers to count. However, humans did not write numbers as we do today. For example, the Romans used the “digits” I (1), V (5), X (10), L (50), C (100), D (500), and M (1000) to write down numbers. When they had to write a number, they “decomposed” the number into parts corresponding to quantities equal to the available “digits” and then they simply wrote down the corresponding “digits”. Thus, the number 2017 was written as MMXVII. The alphabetic numeral system of Ancient Greeks was similar. The table below shows the modern form of its “digits”.

Thus, the number 2017 is rendered as

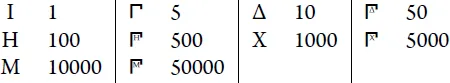

. The so-called acrophonic numbering system was another system that was used by Ancient Greeks. Its set of “digits” is shown below:

In this system the number 2017 is written as XXΔ

II.

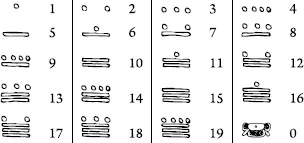

Interestingly, not all humans have been using the decimal numeral system. Many people, including the Mayas and the Aztecs, have been using a numeral system that had the number 20 as its basis. This numeral system is called vigesimal. It is quite possible that the Mayas and the Aztecs have been using the fingers of both their hands and their feet for counting and this might explain why they have opted to use the number 20 as basis for their numeral system. The table that follows shows the various “digits” used to write numerals.

Numbers in this system are written from top to bottom, and the most significant digit is always at the top. For example, the number 2017 would be rendered as follows:

These are not the only numeral systems people have ever used. The Ancient Sumerian people had used a numeral system with 60 as its basis (such a system is called sexagesimal). Unfortunately, there is no reasonable explanation, just speculations, for this peculiar choice. This system is unique such that the numbers 2, 120, 7200, and 1/30 were all written in an identical manner. Moreover, this number system is still in some use even today. The fact that 1 hour has 60 minutes and 1 minute has 60 seconds has its roots to the Sumerian numeral system. Since humans had used the numbers 10, 20, and 60 to specify numeral systems, it makes sense to say that any number can be used as a basis for a numeral system. For example, one can use the numbers 2, 8, and 16 as bases for numeral systems that are called binary, octal, and hexadecimal. It is possible to use a negative number or even an imaginary number as a basis for a numeral system! Nevertheless, these exotic numeral systems will not concern us in what follows.

In ancient Egypt, agriculture had been developed by making use of the dry and rainy seasons. It was very important to know when these seasons were to arrive. Initially, they might have used some rules of thumb to predict these seasons. Later on, they developed a calendar to precisely predict the seasons. Developing a calendar means that one is able to record numbers and text, that is, one has a writing system at her disposal. The writing system should also provide some means so as to perform some, if not all, arithmetical operations. After all, it is not easy to work difficult operations “in your head”. The Egyptians developed such methods but they were adequate only for additions and subtraction while there was provision for fractions. All civilizations that developed a writing system also developed notations for numbers and methods to perform arithmetical operations with these notations. Sooner or later, merchants, astronomers, and all the people who heavily used numbers in their everyday business discovered that they needed faster and easier ways to do arithmetical operations and so the demand for devices that could assist humans in such operations was presumably high.

The first device that could assist humans to perform arithmetical operations fast is the abacus. An abacus consists of beads that can be moved up and down on a series of sticks or strings within a wooden frame usually. The abacus is found in almost any nation in every part of the planet. An abacus can be used to perform additions and subtractions easily, while it is not very difficult to perform multiplications. Divisions are much harder.

The Greek mathematician Eratosthenes of Cyrene (’Eρατoσθ

νης) is best known for being the first human to calculate the circumference of the Earth. In addition, Eratosthenes built a calculating device, which was called

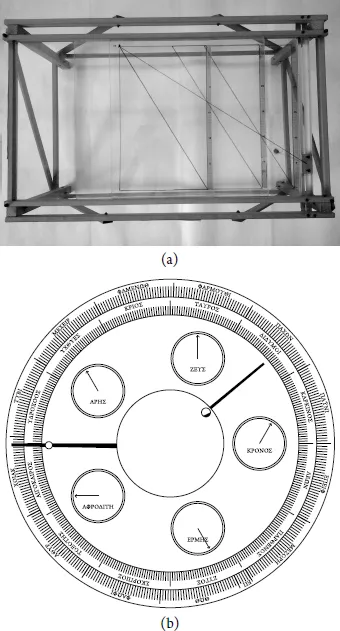

mesolabio [see

Figure 1.1(a)], for easing the labor involved in solving a particular problem. The mesolabio consisted of three rectangular frames of equal size that could slide on a rail at their base so they could be partially superimposed on one another. Each frame had a string stretching over the diagonal. The mesolabio was invented in order to solve the Delian problem, that is, the construction of a cube with twice the volume of a given cube using only a straightedge and compass. In the 19th century, mathematicians showed that this problem could not be solved using the tools originally specified. However, Eratosthenes solved the problem using the mesolabio. In a sense, he did not solve the problem but gave an answer to the first part of the problem, that is, whether it is possible to construct a cube with twice the volume of a given cube. The important lesson to learn here is that it might be possible to solve problems by relaxing some initial constraints and/or conditions (see

Section 3.1 for a detailed discussion of problems and their solutions).

Without doubt, the most impressive device of antiquity is the Antikythera mechanism,

1 which was recovered from an ancient shipwreck in 1901 and was probably built sometime between 150 BC and 60 BC. More than a century has passed since the mechanism was recovered, yet there is no real consensus regarding its purpose. However, one can say that the device encompasses what was known about the Universe [or “Cosmos” (Kόσμος) as this word is inscribed on the mechanism] at the time of its construction. Thus, it is not an exaggeration to say that the mechanism was some sort of mechanical encyclopedia of astronomy. The device was probably enclosed in a wooden box whose height was 320–330 mm, its width 170–180 mm, and its depth 80 mm. The box was found inside more than 30 toothed wheels. On one side of the box, there was a handle and the user had to turn it in order to operate the mechanism.

Figure 1.1(b) shows a reconstruction of the front display of the Antikythera mechanism. The front display contained two large pointers — the bigger one showed the date in the Greek–Egyptian calendar (the outer annulus showed Egyptian month names) and the smaller one showed the position of the moon on the zodiac scale (inner annulus showed the name of the 12 zodiac signs). The little ball on the smaller pointer showed the phases of the moon. In addition, there are fine planetary dials (little circles). Each dial corresponds to one of the known planets at the time: Saturn (KPONOΣ), Jupiter (ZE

Σ), Mars (APHΣ), Venus (AΦPOΔITH), and Mercury (EPMHΣ). It is quite possible that these dials could have shown key events in each planet’s cycle. Naturally, one could infer that when the two big pointers overlapped, then an eclipse should happen. Thus, the device could predict eclipses, among others.

2 Strictly, the mechanism is not a calculating device, but it does have the capability to perform multiplication and division. All these prove that technology was quite advanced in antiquity and not so much primitive as we typically think.

Figure 1.1: Eratosthenes’s mesolabio and the front display of the Antikythera mechanism. (a) A replica of Eratosthenes’s mesolabio. Image courtesy of Laboratorio delle Macchine Matematiche dell’Università di Modena e Reggio Emilia. (b) This front display of the Antikythera mechanism is based on its latest reconstruction (see text for a description of its various parts). Image created by the author using the

TikZ package from a drawing that appeared on Nature, Vol. 468, pp. 496–498 (2010).

The next milestone in the development of calculating devices is the Rabdologia, or Napier’s Bones, as they are more commonly known, after their inventor John Napier, who was a Scotsman whose main discovery is the logarithm. Rabdologia is based on the use of Gelosia, a method for doing multiplication, which was most likely developed in India. This is not a device like the Antikythera mechanism, which had gears and worked much like a clock, but something similar to the abacus. The Jesuit Athanasius Kircher implemented the idea of incorporating Rabdologia into some form of mechanical assembly. This device is known as Organum Mathematicum (see Figure 1.2). The slide rule was another device that was inspired by Napier’s work. It was developed by William Oughtred and others.

1.2Mechanical Calculating Devices

In a sense, Organum Mathematicum (see Figure 1.2) was a precursor to the mechanical calculating devices that were developed in the 16th century and afterwards. Wilhelm Schickard, who was a Professor of Hebrew, Astronomy, Mathematics, and Geodesy at the University of Tübingen, Germany, designed and built a device, the Rechen Uhr (calculating clock), in 1623. The calculating clock was the first mechanical calculating device. Unfortunately, no copy of the machine has survived. What we know about this machine is contained in three documents: two letters between Schickard and his close friend Johannes Kepler, and a sketch of the machine with instructions to a workman. The sketch is not so elaborate, but the hints provided in the letters were useful enough to reconstruct the machine.

The French mathematician and philosopher Blaise Pascal is the second person who designed and constructed a mechanical calculating machine. Using the Pascaline [see Figure 1.3(a) on page 8], as the machine is known, was quite easy. In fact, one could perform additions and subtractions. Multiplications were possible by repeatedly performing additions while divisions were not out of question. Pascal tried to put his invention into production. Although this was not a profitable move, still this is the reason why a large number of Pascalines survived till today.

Figure 1.2: A replica of Organum Mathematicum. Image courtesy of Museo Galileo, Florence, Photo Franca Principe.

Gottfried Wilhe...