![]()

Part I

Foreign Trade

![]()

Chapter

1

Income and Price Effects in Foreign Trade*

Morris Goldstein and Mohsin S. Khan

1.INTRODUCTION

Few areas in all of economics, and probably none within international economics itself, have been subject to as much empirical investigation over the past thirty five years as the behavior of foreign trade flows. Reasons for this unusual degree of attention are not hard to find. First, the data base is a rich one.1 Statistics on the value of imports and exports extend over long time periods and can be disaggregated by commodity and by region of origin or destination to a relatively fine level.2 Second, the underlying theoretical framework for the determination of trade volumes and prices is a familiar one from consumer demand and production theory, and can make do with relatively few explanatory variables, most of which have accessible empirical counterparts. Third, the estimated income and price elasticities of demand and supply have seemingly wide application to a host of important macro-economic policy issues, including but not limited to: the international transmission of changes in economic activity and prices, the impact of both expenditure-reducing (monetary and fiscal) policies and expenditure-switching (exchange rate, tariff, subsidy) policies on a country’s trade balance, the welfare and employment implications of changes in own or partner-countries’ trade restrictions, and the severity of external balance constraints on domestic policy choices.

In this chapter the aim is to identify, summarize, and evaluate the main methodological and policy issues that have surrounded the estimation of trade equations. By “trade equations” we mean equations for the time-series behavior of the quantities and prices of merchandise imports and exports,3 and as the title of the chapter suggests, we focus explicitly on the role played by income and prices in the determination of these trade variables.

Our task is made easier by the admirable coverage of the early empirical literature and of many specific topics in trade modelling in previous survey papers. Indeed, trade surveys have appeared at least once every five years since 1959. Early (1936–57) estimates of income propensities and price elasticities have been surveyed and evaluated by Cheng (1959) and by Prais (1962). Early world trade models are discussed in Taplin (1973), and more recent multi-country models are compared and analyzed by Deardorff and Stern (1977) and by Fair (1979). Special mention should be made of the comprehensive trade surveys of Leamer and Stern (1970), Magee (1975), and Stern et al. (1976). The Leamer and Stern (1970) book has, among other things, a lucid discussion of the time-series estimation of import and export demand relationships. In this chapter we have tried to update and expand upon their analysis of methodological issues; in particular; we devote more attention to supply relationships.4 Magee’s (1975) trade survey is the broadest one available, encompassing methodological questions, empirical evidence, pure trade and monetary theory, and associated policy issues. We inevitably therefore cover some of the same ground but we have tried to minimize duplication.5 Finally, Stern et al. (1976) have provided an exhaustive annotated bibliography of price elasticity studies in international trade spanning the 1960–1975 period, as well as summary tables of “median” price elasticities broken down by commodity group and by country. We offer our own updated “consensus” price and income elasticities which partially reflect Stern et al.’s (1976) findings but which also give higher weights to what we regard as the better quality estimates.6

The plan of the chapter is as follows. Section 2 addresses the main methodological issues in the specification of trade models. This is basically a discussion about what variables ought in theory to be included in demand and supply functions for imports and exports, what choices and compromises have to be made in the measurement of these variables, and what light existing evidence throws on the choice among competing specifications. Section 3 is concerned with what we call econometric issues in trade modelling. The subjects covered are the treatment of dynamics and time lags, aggregation, simultaneity, and stability of the relationships concerned. Section 4 turns to the empirical estimates of income and price elasticities themselves and to the policy implications of those estimates. Summary tables are constructed from recent empirical studies to illustrate the revealed “consensus”, or lack of it, on (i) long-run price and income elasticities of demand for total merchandise imports and exports; (ii) the difference between short-run and long-run price elasticities of demand; (iii) price and activity elasticities for broad commodity classes of imports; (iv) supply price elasticities for exports, (v) the so-called “pass-through” of exchange rate changes onto the domestic currency prices of imports and exports; (vi) the elasticity of export price with respect to domestic prices (or labor costs) and competitors’ export prices; and (vii) the “feedback” effect of exchange rate changes on domestic prices. Drawing on this evidence, broad conclusions are advanced on the effectiveness of devaluation. Section 5 offers some concluding observations as well as suggestions for further research.

2.SPECIFICATION ISSUES IN TRADE MODELLING

How should the time-series behavior of imports and exports be modelled? In our view, the appropriate model depends on, among other things, the type of good being traded (perfectly homogeneous primary commodities versus highly differentiated manufactured goods), on the end-use to which the traded commodity is being put (whether for final consumption or as a factor input), on the institutional framework under which trade takes place (an economy where resources are allocated via relative prices versus one where administrative controls play the predominant role in allocation), on the purpose of the modelling exercise (forecasting versus hypothesis testing), and sometimes even on the availability of data (e.g. if reliable data exist on trade values but not on volumes).

Nevertheless, it still makes sense as a framework for the discussion of particular specification issues to set out the two general models of trade that have dominated the empirical literature, namely, the imperfect substitutes model and the perfect substitutes model. Since most trade studies have dealt with aggregate imports (exports), the two models have often been viewed as competitors. Once disaggregation is admitted, however, there is no reason why the two models should not be seen as complements — one dealing with trade for differentiated goods, and the other with trade for close — if not perfect — substitutes.7

2.1.The Imperfect Substitutes Model

The key underlying assumption of the imperfect substitutes model is that neither imports nor exports are perfect substitutes for domestic goods. Support for this assumption comes from two sources. First, there is the (debating) argument that if domestic and foreign goods were perfect substitutes, then one should observe: (i) either the domestic or foreign good swallowing up the whole market when each is produced under constant (or decreasing) costs [Magee (1975)]; and (ii) each country as an exporter or importer of a traded good but not both [Rhomberg (1973)]. Since both of these predictions are counter to fact at both the aggregate and disaggregated level, i.e. one normally observes the coexistence of imports and domestic output and the flourishing of two-way trade, the perfect substitutes hypothesis can be rejected. The second bit of evidence is more direct. A large number of empirical studies [Kreinen and Officer (1978), Isard (1977b), Kravis and Lipsey (1978)] have shown that, even at the most disaggregated level for which comparable data can be gathered, there are significant and nontransitory price differences for the “same” product in different countries (after translation into a common currency), as well as between the domestic and export prices of a given product in the same country. In short, the “law of one price” does not seem to hold either across or within countries, except perhaps for standard commodities such as wheat or copper that are sold on international commodity exchanges.8 It would appear therefore that finite price elasticities of demand and supply can in fact be estimated for most traded goods.

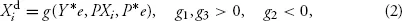

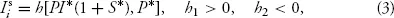

In eqs. (1)–(8) below, we present a “bare-bones” imperfect substitutes model of country i’s imports from, and exports to, the rest of the world(*):

These eight equations determine the quantity of imports demanded in country

i , the quantity of country

i’s exports demanded by the rest of the world

, the quantity of imports supplied to country

i from the rest of the world

,

9 the quantity of exports supplied from country

i to the rest of the world

, the domestic currency prices paid by importers in the two regions (

PIi and

PI∗), and the domestic currency prices received by exporters in two regions (

PXi,

PX∗). The exogenous variables are the levels of nominal income in the two regions (

Yi,

Y∗), the price of (all) domestically produced goods in the two regions (

Pi,

P∗), the proportional tariff (

Ti,

T∗) and subsidy rates (

Si,

S∗) applied to imports and exports in the two regions, and the exchange rate (

e) linking the two currencies (expressed in units of country

i’s currency per unit of the rest-of-the world’s ...