![]()

1.A Brief Introduction to Proteinases

Constance E. Brinckerhoff

Exactly how proteinases act on their various protein substrates is a critical component in almost all aspects of normal physiology and disease pathology.1 Therefore, any discussion on matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) must place these enzymes in the context of other classes of proteinases in order to fully understand and appreciate their contributions to biology. Many proteinases show exquisite specificity in targeting their protein substrate, whereas others are far more promiscuous, showing broad degradative activity against many substrates.1

Data assembled from a variety of public and private sequencing databases and from the MEROPS, InterPro, and Ensemblrecords have identified at least 550 genes that encode proteases in the human genome, often with murine counterparts.1 Of these, nearly 100 are enzymatically inactive due to substitutions in amino-acid residues that are in regions of the proteinase that are needed for the enzyme to retain proteolytic activity. Interestingly, it has been suggested that these inactive homologues have important regulatory or inhibitory molecules, by functioning as dominant negatives or by “sopping up” inhibitors from the local environment, and thus permitting increases in proteolytic activity.1 This intriguing concept implies additional and novel functions for proteases, beyond their direct enzymatic actions, a concept that has been realized with MMPs.

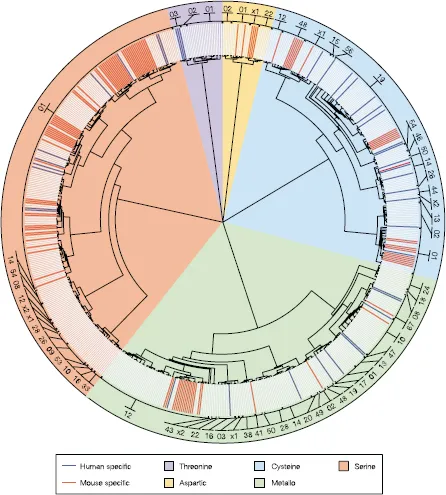

Five classes of proteinases have been designated based on mechanisms of catalysis: aspartic, cysteine, threonine, serine, and metalloproteinases.1,2 The metalloproteases and serine proteinases have the most members, with 186 and 176 enzymes, respectively, followed by the cysteine proteases, of which there are 143 enzymes (Figs. 1.1 and 1.2).3 The threonine and aspartic proteases have very specific functions and are less common and have only 27 and 21 members, respectively.1 The aspartic and metalloproteinases use an activated water molecule to mediate a nucleophilic attack1 on the peptide bond of the substrate, while in the cysteine, serine, and threonine proteinases, the nucleophile is an amino acid (cysteine, serine, or threonine) located in the active site of the enzyme. For the degradation of matrix proteins, these proteinases are primarily “endopeptidases”, that is, they cleave peptide bonds within the matrix molecule. They are synthesized as inactive precursors, or “pro-enzymes”, which must be activated proteolytically either by autocrine or paracrine mechanisms. The proform of endopeptidases is a critically important regulatory step that prevents indiscriminate and rampant proteolytic activity.1,4

1.1Aspartic Proteinases

These proteinases have two aspartic acid residues as an integral component of their catalytic site.1,4 Aspartic proteinases are active at acidic pH and inactive at neutral pH. Mostly, they are enzymatically active extracellularly in the pericellular space, where the pH is sufficiently low (pH 3.5–5.5). Intracellularly, they are active in lysosomes or in a microenvironment where the pH is between 5.5 and 7.0. Examples of aspartic proteinases include pepsin, renin, HIV protease, and the lysosomal cathepsins D and F. Aspartic proteinases have broad substrate specificities. However, they function within in a somewhat narrow biological context, which is defined by optimal pH and their own particular ability to target a specific substrate.

1.2Cysteine Proteinases

Cysteine proteinases also function optimally at an acid pH and, like the aspartic proteinases, they are usually stored in lysosomes.1,4 These proteases have a catalytic mechanism that involves a nucleophilic cysteine thiol in a dyad or triad, that is, two or three amino-acid residues that function together at the center of the active site. Cysteine proteases have several roles in extracellular matrix (ECM) remodeling. Lysosomal cysteine proteinases secreted from osteoclasts facilitate bone resorption by degrading collagen. They are often involved in the digestion of phagocytosed materials, giving them a prominent role in activated macrophages. Cathepsins B, L, N, and S and the calpains are a few examples of cysteine proteinases. Other cysteine proteinases are Cathepsins B and L, which may be present extracellularly, especially in activated macrophages. These cathepsins can cleave the nonhelical regions of fibrillar collagens at acid pH, leading to depolymerization of collagen fibrils. Hence, they are sometimes referred to as “collagenases” although they do not meet the classical definition, which is “an enzyme that catalyzes the hydrolysis of peptide bonds in triple helical regions of collagen”.5 Cathepsins L and S also attack elastin, giving them a role in ECM metabolism. Thus, cysteine proteinases are ubiquitous and can contribute substantially to matrix remodeling in health and disease, either alone or in combination with other classes of proteinases.

Figure 1.1. The protease wheel. Unrooted phylogenetic tree of human and mouse proteases. Proteases are distributed in 5 catalytic classes and 63 different families. The code number for each protease family is indicated in the outer ring. Protein sequences that correspond to the protease domain from each family were aligned using the ClustalX program. Phylogenetic trees were constructed for each family using the Protpars program. A global tree was generated using the protease domain from one member of each family, and individual family trees were added at the corresponding positions. The figure shows the nonredundant set of proteases. Orthologous proteases are shown in light gray, mouse-specific proteases are shown in red, and human-specific proteases in blue. Metalloproteases are the most abundant class of enzymes in both organisms, but most lineage-specific differences are in the serine protease class, making this sector wider. The 01 family of serine proteases can be divided into 22 smaller subgroups on the basis of involvement in different physiological processes, to facilitate the interpretation of differences. (From Puente et al. 2003.)

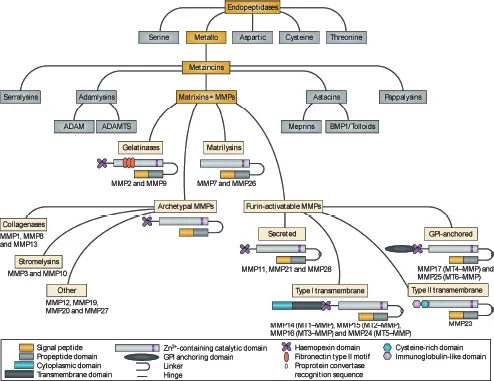

Figure 1.2. Schematic overview of the structure of MMP family members and the relationship with other metzincin superfamily members. MMPs share a common domain structure: the predomain that Nature Reviews | Drug Discovery contains a signal peptide responsible for secretion; the pro-domain that keeps the enzyme inactive by an interaction between a cysteine residue and the Zn2+ ion group from the catalytic domain; and the hemopexin-like carboxy-terminal domain, which is linked to the catalytic domain by a flexible hinge region. MMP7 and MMP26 lack the hinge region and the hemopexin domain. MMP2 and MMP9 contain a fibronectin type II motif inserted into the catalytic site, and MT-MMPs have a transmembrane domain or a glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI) anchor at the C terminus. MMP23 has unique features: the amino-terminal signal anchor that targets MMP23 to the cell membrane, a cysteine array, and an immunoglobulin-like domain. ADAM, a disintegrin and metalloproteinase; ADAMTS, ADAM with thrombospondin motifs; BMP1, bone morphogenetic protein 1. (From Vandenbroucke and Libert 2014.)

1.3Threonine Proteinases

Threonine proteinases are a more recently discovered category of proteinases and they function as a component of proteasomes. Proteasomes are the main mediators of intracellular degradation of a wide variety of cellular proteins and they are implicated in several physiological and pathological cellular functions.6,7 The proteasome pathway is involved in matrix degradation by several mechanisms, which include both transcriptional and posttranslational mechanisms. By controlling the concentration and turnover of several ECM components, the proteasome pathway contributes to extracellular proteolytic events by modulating the expression and activity of MMPs and their endogenous inhibitors (see the following). Therefore, since matrix remodeling and degradation can be controlled by proteasome activities, proteasome modulation might be a novel therapeutic strategy in some pathologic conditions7 and perhaps future studies may reveal additional mechanisms of their action and therapeutic strategies that target them.

1.4Serine Proteinases

Serine proteinases comprise a large family of enzymes, with a broad range of substrates. Consequently, they participate in many important biological processes such as digestion, blood clotting, and immune response.1,4 In contrast to aspartic and cysteine proteinases, they function at neutral pH, cleaving peptide bonds in proteins where serine serves as the nucleophilic amino acid at the active site of the enzyme. Examples of serine proteinases are enzymes involved in digestion (trypsinogen/trypsin, chymotrypsinogen/chymotrypsin), blood clotting (plasminogen/plasmin, prothrombin/thrombin), and homeostasis (tissue and plasma prekallikrein/kallikrein, and tissue remodeling (proelastase/elastase). Further, many serine proteinases are important by acting indirectly on the ECM by activating latent MMPs, cleaving them to their enzymatically active form. Some serine proteinases are stored in azurophil granules of polymorphonuclear (PMN) leukocytes, while others (i.e., tryptase, chymase, and cathepsin G) are secreted. Plasminogen activators (PAs), tissue PA and urokinase PA, are secreted by several cell types, including fibroblasts, chondrocytes, and tumor cells, and convert plasminogen to plasmin. Plasmin then degrades fibrin as well as ECM components such as aggrecan, type IV collagen, and laminin. Kallikrein binds to receptors on fibroblasts, macrophages, and tumor cells, where it helps to coordinate several physiological functions, including blood pressure, liquification of semen liquefaction, and shedding of skin. Serine proteinases are abundant, with many physiologic functions. Given their ability to cleave many substrates and to activate latent MMPs, serine proteinases are important adjuncts to MMPs in ECM degradation.

1.5Matrix Metalloproteinases

MMPs, sometimes called matrixins, belong to the super family of metzincins,2,4,8–11 which is characterized by a catalytic zinc atom at the active site of the enzyme, followed by a conserved methionine (Fig. 1.3). Metzincins contain several subfamilies, including two that have activities related to those of the MMPs, that is, a disintegrin and metalloproteinase (ADAMS) and a disintegrin and metalloproteinase with thrombospondin motif (ADAMTS), metalloproteinases that were first reported in 1992 and 1997, respectively.2,12 ADAMs are membrane-associated enzymes, which are expressed by a wide variety of cell types, and are involved in functions as diverse as sperm–egg binding, myotube formation, neurogenesis, and proteolytic processing of cell surface proteins, giving them the nickname “sheddase”.2,12 A particularly well-known sheddase is tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) converting enzyme (TACE), a unique member of the ADAM family that cleaves this membrane-bound enzyme. The enzymatic activities of ADAMs are varied and include (1) cleaving collagen propeptides, (2) inhibiting angiogenesis, (3) degrading cartilage proteoglycans, and (4) maintaining blood coagulation homoeostasis as the proteinase that cleaves von Willebrand factor. Both ADAMS and ADAMSTS are increasing subjects of study, and many of their functions and ac...