![]()

Chapter 1

Setting Up

Matrix Structural Analysis (MSA) and Finite Element Methods (FEM) are numerical analysis techniques which rely on the reduction of complex physical problems into sets of linear equations solved using computer algorithms. Prior to the 20th century, numerical analysis could only be executed by human or analog computers, which were slow, expensive, and prone to error. The advent of digital computers in the 1940s offered the possibility of accurately performing calculations that could be reduced to a set of simple tasks. Established matrix techniques, which could be reduced to entry-by-entry manipulation, proved to be particularly well-suited for computer execution. The emergence of the Direct Stiffness Method (DSM), the predecessor of MSA and FEM, in the early 1950s facilitated the use of matrix techniques for the analysis of structural systems.

Commercialization of computers has resulted in the proliferation of MSA and FEM in academia and industry. The incredible improvement in the capacity of analysis packages has far outpaced user awareness of the underlying theory and inherent limitations of these tools. Defaults and user-friendly interfaces have made complex code increasingly more accessible to a broader user base while simultaneously obscuring the inner workings of black-box software packages. Although it may be argued that an engineer does not need to know how a software package works as long as it does, the engineer still bears the responsibility of correctly using the appropriate tool for a specific task. With the plethora of elements and analysis techniques available in modern software packages, the permutations of misuse far outnumber those of correct use. Like any method of analysis, MSA and FEM have a particular scope of application and best practice guidelines that cannot be relegated to settings in a program.

MSA and FEM, while grounded in scientific theory and mathematics, both come to life as code. Learning about these matrix techniques can follow one of two strategies: the invested reader can set out to read texts on the subject passively, learning the terminology and theory, even testing out the methods with an associated software package; or, he or she can code in the basic MSA/FEM program directly. While the former method facilitates a broader survey of the material, it is only through writing code that a novice can attain an acute and reliable understanding of MSA/FEM. Many of the characteristics and limitations of advanced software packages originate in basic code; only through an intimate understanding of the fundamental building blocks of MSA and FEM can the reader expect to appreciate the significance of higher level programs.

This text can be seen as a narrated recipe book for coding MSA and FEM; it presents a simple, but robust set of algorithms that make up a basic, but powerful analysis package. The reader is encouraged to engage actively with the code, implementing the various algorithms as they are presented. The content is tailored to an audience of undergraduates, graduate students, and practitioners in the fields of structural and mechanical engineering. Hence, the reader is assumed to have a basic understanding of statics, linear algebra, calculus, and coding. Derivations are designed to lead the reader from fundamental physical and mathematical theory directly to implementable code. Upon reading this text and testing out the code, the reader should feel prepared to read higher level texts and critically assess the results of commercially available analysis packages.

1.1Scope

MSA and FEM originated as techniques for solving static and dynamic problems in mechanical and structural engineering but have since spread to a broader scope of application. This text is limited to problems in static linear elasticity and steady-state heat.

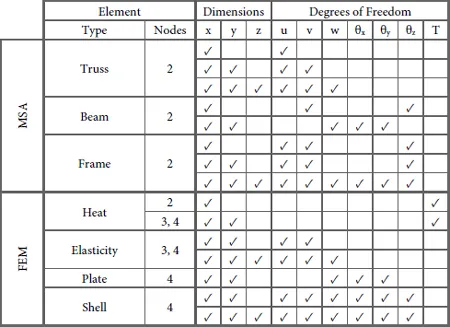

Trusses, beams, and frames delimit the traditional territory of MSA. For each element, we present the basic stiffness formulations and demonstrate how to extract internal element forces (axial force, moment, shear, and torsion as applicable).

We begin our investigation of FEM via steady-state heat. Besides being a common engineering problem, heat only has one degree of freedom (temperature) allowing for a simple derivation of the basic stiffness formulation. Next, we derive basic three- and four-node elastic elements and conclude with bending-capable plates and shells.

It is worth stressing that this book is concerned with analysis, not design. Though they may share variables and vocabularies, the tools of design and analysis are distinct. Analysis is broadly defined as the extraction of information that describes the performance of a particular physical system. Typically, the unknown information in a structural problem consists of reaction forces, internal element forces/stresses/strains, and displacements. This information may in turn inform design decisions regarding global geometry, element sections, and material choices. Of course, we cannot perform an analysis without a starting point for these variables; the exchange between analysis and design is thus iterative, in some cases permitting parametric optimization. The types of analysis covered in this book are far from the only methods available to the student or practicing engineer. Engineers should always verify any computer-aided analysis using a simplified set of hand calculations. Engineers designed highly efficient, elegant structural systems well before MSA and FEM came into existence. While new analytical techniques help fine-tune the final design, the importance of conceptual design via traditional techniques should not be overlooked.

It is important to moderate the accuracy of any analysis in reference to the reliability of the measurements or assumptions used. For instance, standard gravity on Earth varies from 9.83 m/s2 at the North Pole to 9.78 m/s2 at the equator, resulting in a variation of 0.5% in gravity across the world. Since most structural analysis is based on assumed standard gravity, reporting results to more than four significant figures is misleading. When we consider how much less reliable our predictions are of other forms of loading, material properties, support conditions, or fabrication accuracy, we can see the false security of reporting overly accurate analysis results.

1.1.1A Basic Structural Analysis Problem

Structural analysis requires the engineer to formulate a real-world scenario as an idealization appropriate to a form of analysis. The engineering student typically forfeits this step to permit a pedagogical direction particular to the analysis undertaken. Although we do not divert from this strategy, the reader should remain cognizant of the idealizations inherent to any form of analysis.

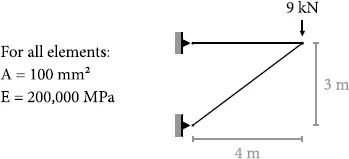

In this section, we will analyze a basic truss structure with properties, supports, and loads as shown:

Figure 1.1. A basic structural problem composed of truss elements.

Our first step in solving this structural problem is to identify knowns and unknowns. The problem setup provides known element properties (sectional and material), geometry, applied loads, ...