![]()

Chapter 1

The Earliest Times: 1786–1850s

The Straits of Malacca are so situated as to permit whoever commands them to control seaborne trade between points East and West. In the days of sailing ships, and because of commercial and territorial rivalry among European powers at the time of the Napoleonic wars, Britain desired a base in the Straits in order to facilitate the then flourishing trade between British India and China, to compete with the Dutch (who were trying to maintain a monopoly of trade in the East Indies Archipelago) and to hold at bay any attempted invasion of the region by French commercial interests.

Britain’s foothold in the region was gained in 1786, when the island of Penang was acquired by the British East India Co. Province Wellesley, across the water, was added to it in 1798. In 1805 the Penang jurisdiction was raised to the administrative status of fourth presidency of British India. The East India Co. acquired Singapore in 1819 and Malacca (as part of an intricate territorial deal with the Dutch) in 1824.

Much has been written about the foundation of Singapore and there is no need to repeat the tale here. Suffice it to note that the British had become very concerned about the possibility that the Dutch, who already had a firm hold on the Sunda Straits, might also gain command of the Straits of Malacca and thus control both channels of trade between China and Europe. Accordingly, the Governor-General of India, the Marquess of Hastings, instructed Sir Stamford Raffles to endeavour to establish a British station to command the eastern entrance to the Straits of Malacca; he indicated that Rhio was perhaps the most suitable location, with Johore as a possibility if Rhio was unavailable. On finding Rhio already occupied by the Dutch, Raffles, interpreting his supplementary instructions rather freely, made an on-the-spot decision that the sparsely-inhabited island of Singapore was the best location and dropped anchor there on 28 January 1819, and within a short while made a treaty with the Malay Sultanate of Johore for the East India Co. to make and maintain a settlement on Singapore. The British merchants in Calcutta welcomed this outcome and their approbation supported Hastings in his support of Raffles (Collis, 1982, gives a concise and lively account of this period).

Penang, Singapore and Malacca were combined in 1826 into the Straits Settlements (S.S.), administered as a Presidency of India by the East India Co. until 1858, and then by the India Office until 1867. In that last year, the S.S. were separated from the India administration and given the status of Crown Colony under the control of the Colonial Office in London. British suzerainty in Malaya was confined to the S.S. until 1874, when the first political encroachment on the Malayan hinterland was made.

In the 90 or so years between 1786 and 1874, international commerce was essentially confined to entrepot trade between India, China and Europe which necessarily passed through the conveniently located Straits ports. “Entrepot” trade consists of import and re-export as distinct from importing foreign goods for local use and exporting local produce. “Transhipment”, to be mentioned later, is a particular form of entrepot in which the imported commodities are not sold in the local entrepot market before re-export but simply transferred from one ship to another without any change in ownership of the goods. The trade of the S.S. also included the export of produce from the East Indies archipelago and the Malay Peninsula and a return flow of imports to those points. But the peninsula was sparsely settled and largely undeveloped until at least the 1850s. The S.S. initially waxed rich on the much larger entrepot trade.

The S.S. flourished under the umbrella of Britain’s then powerful position in world trade and through a total commitment to the philosophy of free and unrestricted trade. Penang began under Francis Light’s administration in 1786 as a free port, then uniquely so in Southeast Asia (Tregonning, 1965, p. 59); but in 1801, in a desperate search for government revenue, the administration of Sir George Leith imposed import and export taxes (ibid., p. 63). However, these were abolished in 1826 after the unification of the S.S. ports as a single administrative unit.

The free trade policy of Singapore became the rule for the S.S. (ibid., p. 72). Raffles, the founder of Singapore, had introduced a policy of free trade at the very beginning although, as Tregonning points out, not with any great enthusiasm for the principle. “It is not necessary at present to subject the trade of the port to any duties — it is yet inconsiderable; and it would be impolitic to incur the risk of obstructing its advancement by any measure of this nature” (ibid., p. 154).

However, by 1822 Raffles was more positive in proclaiming:

Further, in a long letter instructing a small committee (Captain C.C. Davis, and Messrs George Bonham and Alex L. Johnston) to advise on the appropriation of land in Singapore, Raffles wrote, “it will be a primary object to secure to the mercantile community all the facilities which the natural advantages of the port afford.” (Notices of Singapore, Journal of the Indian Archipelago and Eastern Asia (JIA), VII, 1853, p. 335 and VII, 1854, p. 102.)

Raffles’ administrative successors found themselves — willy nilly — locked into the free trade policy, dictated from London and buttressed by the powerful merchants of Singapore.

By the late 18th century the East India Co. had become too cumber-some and bureaucratic an organisation to handle the fragmented river and coastal trade of the East Indies archipelago and of the mainland Malay, Burmese and Siamese states. This profitable and risky trade was conducted by the so-called “country traders” who plied the seas of Southeast Asia. These men worked the numerous small ports scattered around the islands; they formed loose trading associations, centred on Madras, and sailed under the British flag licensed by the company’s authorities in Indian Presidency towns; but they were not members of the East India Co.

One such country trader was Light, employed as an agent of the Madras association of Jourdain, Sulivan and De Souza (Tregonning, 1965, pp. 7–9, 14). As early as 1771, Light had commended Penang as a desirable location for a trading settlement:

Light was appointed by the East India Co. 15 years later to be Superintendent of its newly acquired island of Penang. He retained his trading interests, in partnership from 1787 with James Scott as Scott & Co. (afterwards Brown & Co.), until his death in 1794. Scott apparently was to have sole charge of the firm, leaving Light free to administer the settlement so as to facilitate trade (Fielding, 1955, p. 38). It has been said that Light refrained from abusing “the combined position of Superintendent and principal merchant in Penang” (Skinner, 1895, p. 7). Light’s own protestations to the Governor-General are also on record (Notices of Pinang, JIA, IV, 1850, pp. 652–653).

However, a more critical assessment of Light’s merchant association with Scott and of the activities of Scott & Co. has been made (Stevens, 1929, pp. 379–385, 388). A contemporary critic, Captain Kyd the surveyor, claimed that Light and Scott constituted “so great a bar to all free enterprise that no commercial house or merchant of any credit had ever attempted to form an establishment” (quoted by Tregonning, 1965, p. 166). Fragmentary evidence lends some weight to that view. At the beginning of June 1793, Messrs James Scott & Co. accounted for 123,219 of a total of 182,702 Spanish dollars’ value of goods and merchandise upon the island belonging to British subjects there; and for seven of a total of 10 vessels, and 131,073 of a total of 168,573 Spanish dollars’ value of vessels and cargoes belonging to British inhabitants of the island, at sea in the Straits of Malacca and eastward (JIA, IV, 1850, p. 662).

Members of the East India Co.’s marine service were allowed, subject to some restrictions, from 1796 to trade on their own accounts and many did so. In 1813, the trade of India was thrown open to private traders and it became more attractive for East India Co. mariners to work independently than to remain in the Co.’s service, where pay was now fixed and the privilege of private trading as a sideline abolished (Cunyngham-Brown, 1971, pp. 16, 38). The opening of the India trade also attracted new merchants to the East, as did the British occupation of Java in 1811 and the abolition of the East India Co.’s monopoly of trade with China in 1833. From then on, the eastern trade was wide open to all comers.

In 1819 James Matheson, on route to China, had written:

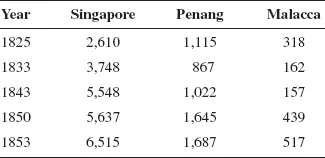

The deficiency was indeed soon remedied. Within very few years after its foundation, Singapore outstripped the other two ports in importance as Table 1 shows. Inevitably, therefore, the emphasis remained on Singapore right up to the last quarter of the 19th century, when merchant firms and banks at last felt the need for permanent and substantial representation on the Malay peninsula.

Table 1. Total Trade (Exports and Imports) (£’000s).

Sources: Cameron, 1965, p. 179; Winstedt, 1966, p. 61.

In 1827 the European population in Singapore numbered 94, in 1833 they were 119 and by 1841 about 300. At the census of 1845, the European population was enumerated at 336, in 1849 at 360 and in 1860 at 466 of whom 271 were adult British males (Turnbull, 1969, p. 13). Many of these men were principals or employees of merchant firms. Those firms numbered 14 in 1827 (Wong, 1960, p. 167) and 17 in 1834 (listed in Table 2 and including many of the pioneering merchants) and 20 a year later (Earl, 1971, p. 415).

The only available contemporary remarks about the early British merchants are by John Crawfurd (in 1824 the Resident of Singapore), T.J. Newbold (an army officer who served in the S.S. in 1832–1835) and G.W. Earl (who resided temporarily in Singapore in 1833–1834). Crawfurd recorded in his General Report on Singapore dated 9 January 1824: “There are 12 European firms, either agents of or connected with good London or Calcutta houses, some have branches at Batavia, and not one can be called an adventurer.” (Notices of Singapore, JIA, IX, 1855, p. 468.)

Newbold wrote: “Few of the European merchants at Singapore transact business on their own account, being mostly agents for European houses.” (Newbold, 1971, p. 352.)

Earl wrote: “The British merchants are chiefly commission agents, who receive consignments of goods from merchants in Great Britain and make returns in oriental produce purchased in the settlement.” (Earl, 1971, p. 416.)

Table 2. List of Merchant Firms in Singapore by 1834 Showing the Years in Which They Were Founded.

1.A.L. Johnston & Co., 1819 or 1820

2.Guthrie & Co., 1821

3.George Armstrong & Co., 1822

4.John Purvis & Co., 1822

5.Syme & Co., 1823

6.Spottiswoode & Connolly, 1824

7.Jose D’Almeida & Sons, 1825

8.Maclaine Fraser & Co., 1825

9.Crane Bros., 1825

10.Maxwell & Co., existing by 1827

11.Morgan Hunter & Co., existing by 1827

12.Napier, Scott & Co., existing by 1827*

13.Thomas & Co., existing by 1827

14.Ker, Rawson & Co., 1828

15.Boustead & Co., 1830

16.Hamilton, Gray & Co., 1832

17.Shaw, Whitehead & Co., 1834

* But apparently founded in 1819.

Source: Loh, 1958, p. 64.

It cannot be inferred from these observations that the merchant fir...