![]()

Chapter 1

China’s Economic New Normal

John WONG*

High Growth Coming to an End

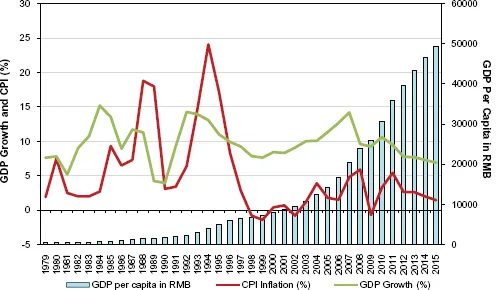

China’s economy has experienced spectacular performance since its economic reform and the open-door policy in 1978, growing at an average annual rate of 9.7% during the 1979–2014 period, and about 10% for the two subperiods of 1991–2014 and 2001–2014.1 Its growth was barely affected by the 1997 Asian financial crisis. Neither did it suffer much from the 2008 global financial crisis, which brought most economies to grief. In fact, China’s economic growth in 2009, following the government’s injection of a massive stimulus package of four trillion yuan, remained at 9.2% and quickly bounced back to 10.4% in 2010, leading the global economy to recovery. In a sense, China’s long streak of high growth performance is simply historically unprecedented (Figure 1).

China’s growth has started to decelerate in recent years primarily due to structural problems and the less conducive global economic environment, with 2014 registering only 7.4% growth. For 2015, growth was originally targeted at 7% but ended up at a still lower 6.9%, the lowest in 25 years. Growth in the first two quarters of 2016 registered only 6.7%, indicating that growth has further come down, though apparently stabilising for a while. As the long-term outlook on growth is still under strong downward pressures, the slowdown as a process is set to continue and sustain.

Figure 1: China’s GDP, CPI and Economic Growth

Source: National Bureau of Statistics.

In other words, China’s economy has already lost its former high growth momentum and is heading for a lower and lower growth in a gradual manner. Viewed from a different perspective, China’s present “lower” growth is “low” only in China’s own terms as its current level of growth at around 6.7% for such a huge economy of about U$11 trillion is still remarkably high by any regional or global standard, and certainly well above the International Monetary Fund’s (IMF) average global economic growth of 3.3% for 2015.

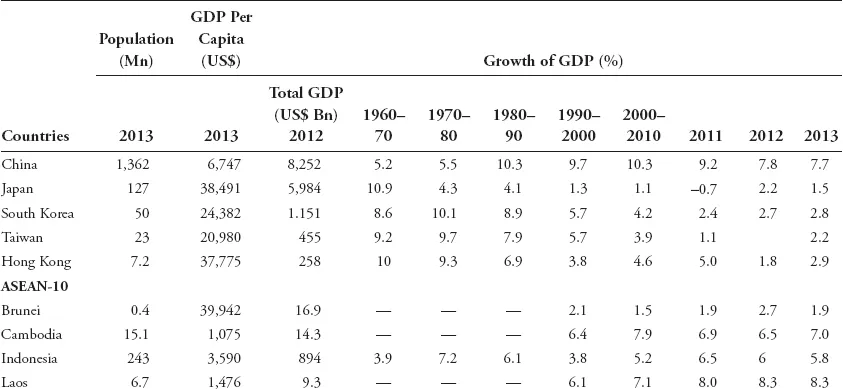

No economy can keep growing at such high rates without running into various constraints. China has chalked up double-digit rates of hyper growth for well over three decades, historically much longer than what other high-performing East Asian economies of Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, Hong Kong and Singapore had experienced before — just a little over two decades of such high growth for Japan, Korea and Taiwan, and a bit shorter for Hong Kong and Singapore. As can be seen from Table 1, Japan experienced such high growth mainly in the 1950s and the 1960s, followed by Hong Kong, South Korea, Taiwan and Singapore after the mid-1960s, the whole of the 1970s and then much of the 1980s. Malaysia and Thailand also had high growth, but not nearly as high and lasting, while India’s growth performance was even more lacklustre.

China has been most remarkable for sustaining such high growth for so long. This is partly because China had enjoyed some latecomer’s advantages in terms of reaping the technological backlog, but mainly because it had far greater internal dynamics in terms of having much bigger hinterlands along with a larger labour force, as compared to that of other East Asian economies. Still, after its catch-up phase of phenomenal hyper growth, China’s growth must come down due to the inevitable weakening of its various growth-inducing drivers or technically, the drying up of its sources of growth.

Weakening of the Main Growth Drivers

From general economic development perspective, the major impetus of China’s growth, on the supply side, is associated with the transfer of its surplus rural labour from low-productivity agriculture to higher-productivity manufacturing, a-la Arthur Lewis.2 However such growth potential has been rapidly exhausted in recent years. China’s population of age group 15–64 had started to peak in 2010 at 74.5%, with the labour supply coming near to the so-called “Lewis Turning Point”. Although these potentially bad demographics have yet to be translated into immediate labour shortages, it does imply that China has already spent most of its “demographic dividend” and started to lose its comparative advantage in a wide range of labour-intensive manufacturing activities. Pari passu with its labour force decline has been the exhaustion of its easy productivity gains from early market reforms and institutional reorganisation, and technological progress embodied in the imported machines and new equipment. Hence the hyper growth has to come to an end.

Table 1: East Asia Economic Indicators

*Myanmar GDP data are estimates based on 2006.

Source: CIA Fact Book.

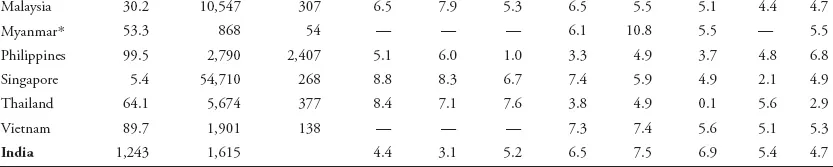

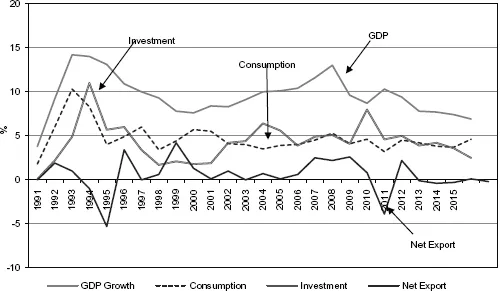

In terms of contribution to growth, China’s economic growth since the early 1990s has been basically driven by total domestic demand, with domestic investment playing a relatively more important role than domestic consumption. This necessarily follows that the contribution of external demand (or net exports) to China’s GDP growth has all along been quite negligible in gross terms, mostly around 5% in the 1990s and then up to around 15% in recent years. During the global financial crisis as China’s exports plunged, the contribution of external demand to overall GDP growth even became negative. It had remained negative in the last few years, turning slightly positive only in 2014. In fact, of the 7.4% growth in 2014, consumption accounted for 3.8% and investment 3.0% while net exports only 0.6% (Figure 2).

It thus appears that the export sector has not directly generated much GDP for China, particularly since China’s exports carry high import contents with around 50% of China’s exports being processing trade. This is because China has been the base for numerous regional and global production networks and supply chains whose finished products usually contain a lot of imported materials and components, thereby netting only a small amount of domestic value-added for China. The classical example was the much publicised case of a China-assembled iPad from Apple that was sold in the US market for US$499, but yielding only US$8 to Chinese labour.3

Figure 2: Sources of China’s Economic Growth, 1990–2015

Source: National Bureau of Statistics.

However, the actual economic importance of Chinese exports to its economic growth has been seriously understated by this first-order simple analysis of gross export figures because it has missed out a lot of important “indirect” economic activities and spillovers that are connected to China’s export industries if we should go for more detailed inter-sectoral analysis. Most export-oriented industries have extensive economic linkages created by various local supporting service activities as well as investment in the upstream and downstream sectors. There are also the multiplier effects on the economy generated by the spending of millions of workers and employees in the export sector.

With rising operating costs and increasing wages, China’s export competitiveness for labour-intensive exports is bound to suffer.4 The sharp rise of China’s unit labour cost in recent years has been widely reported, following its double-digit rates of wage hike. According to official data, the annual average wage of all employees had increased 5.5 times for the past 13 years from 9,330 yuan in 2000 to 51,470 yuan in 2013. Minimum wages had also risen at double-digit rates for the past five years from 2010 to 2015.5 This, along with the gradual appreciation of the renminbi (which has appreciated over 35% against the US dollar since July 2005), had seriously eroded China’s comparative advantage in its export markets. Consequently, China is now facing the same problem of “shifting comparative advantage” that had previously plagued Japan, South Korea and Taiwan. China would soon realise that its export sector is generating less and less growth potential for its economy. Accordingly, exports will no longer be a dependable engine of China’s growth in the long run, not to mention that exports have often been the transmission mechanism of external risks and instability.

This leaves domestic investment and domestic consumption as the principal drivers of China’s future growth. It is well known that China’s past GDP growth has been largely investment-led. Apart from infrastructure development, industrial upgrading and housing construction are the two other major components of fixed assets investment. To cope with the 2008 global financial crisis, Premier Wen Jiabao had hastily put up a huge stimulus package of four trillion yuan to pump-prime the economy, subsequently leading to serious overinvestment as well as an overheated property market. Fixed investment had since come down substantially on account of industrial overcapacity (particularly serious for large industries like steel, cement and ferrous metals with over 20% excess capacities) and a downturn in the property market (real estate accounting for a quarter of total fixed investment). With domestic investment as the main engine of growth rapidly decelerating, GDP growth must also slow down.

Still more, the Chinese economy has been plagued by serious macroeconomic imbalance due to chronic overinvestment and under-consumption, which has led to overproduction and over-export, and eventually persistent trade surplus. In this way, China’s macroeconomic imbalance has also contributed to global macroeconomic imbalances. The root cause of this unique problem is China’s phenomenally high saving rate, which has been, until recently, staying close to 50%.6

China’s high national savings mainly come from its high household as well as high state-enterprises savings. Every year, the state has to mobilise such massive domestic savings for capital investment, from building infrastructure and housing to the technological upgrading of key manufacturing industries. Heavy capital investment had therefore been the foundation of China’s past pro-growth development strategy. However the same strategy had also resulted in its unbalanced growth, with by far too much investment along with too little consumption. Hence the resulting phenomenon of overinvestment and excess capacities, one of the key factors responsible for the lower growth in 2015.

It may be argued that China’s past pro-growth development strategy of “grow first, distribute later” has been the underlying cause of China’s persistent phenomenon of high investment and low consumption. Other East Asian economies from Japan and Korea to Taiwan had also followed similar patterns of investment and consumption before. However such continuing investment-driven growth mode is clearly unsustainable in the long run. Specifically for China, as its population ages, its domestic saving rates are bound to decline over time as is already happening in Japan now. Viewed from a different angle, the fact that consumption is presently not the main driver of China’s economic growth also means that it will be an untapped source of its future growth.

Less Obsessed with GDP-dominated Growth

Back in 1979, Deng Xiaoping launched economic reform to maximise economic growth for China, as manifested in the slogan: “To get rich is glorious”. China’s policymakers have since pursued such high growth strategy, almost at all costs. This had produced double-digit rates of growth for over three decades, with China’s per capita GDP in 2015 about 100 times more than that in 1979. However, such a blatant GDP pursuit (dubbed “GNPism”) had also generated a lot of social costs, ranging from high income inequality (with Gini ratio at 0.47 for 2014) to such undesirable by-products and negative externalities as serious air and water pollution.

This gave the new leadership under Xi Jinping an opportunity to make a decisive departure from China’s time-honoured GDP-dominated pro-growth policy. Thus, China’s National Bureau of Statistics (NBS), which compiles China’s GDP accounts, recently declared that it had taken steps to end what it called “GDP supremacy”. It had radically revised its conventional GDP accounting to give higher weights to the “quality aspects” of GDP growth like innovation and R&D, and to factor in more welfare-aspects of economic growth like the social costs of pollution. NBS also announced that it would provide a more comprehensive and multifaceted assessment of China’s growth performance beyond GDP. In future, along with the release of GDP data, NBS would also provide some 40 or so core indicators that can better capture China’s real economic and social changes, particularly in such crucial areas as industrial upgrading, technological development, environmental protection, rural-urban income gap, urbanisation, people’s livelihood and so on.7 This clearly implies that China’s future economic growth performance will not be epitomised by changes of just one GDP indicator alone.

Finance Minister Lou Jiwei, at the 2014 G20 Finance Ministers Meeting in Cairns (September 2014) confirmed that China had indeed intended to downgrade pure GDP growth in formulating its economic policy and policy response. China’s macroeconomic policy would in future focus more on comprehensive targets like stable growth, employment, inflation and so on. More significantly, the government would stick to the long-term goals of structural reforms and industrial upgrading, and would not, by and large, be distracted by short-term changes in certain GDP indicators.8

In broad principle, as economic growth fluctuates in future, the Chinese government is supposed to refrain from taking hasty stimulus measures just to artificially boost short-term GDP growth. In practice, however, the Chinese government has remained highly averse to any sharp volatility, be it in the stock market, economic growth or employment. As the government tends to maintain reasonably stable growth f...