- 388 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Fundamentals of Nanotransistors

About this book

-->

The transistor is the key enabler of modern electronics. Progress in transistor scaling has pushed channel lengths to the nanometer regime where traditional approaches to device physics are less and less suitable. These lectures describe a way of understanding MOSFETs and other transistors that is much more suitable than traditional approaches when the critical dimensions are measured in nanometers. It uses a novel, “bottom-up approach” that agrees with traditional methods when devices are large, but that also works for nano-devices. Surprisingly, the final result looks much like the traditional, textbook, transistor models, but the parameters in the equations have simple, clear interpretations at the nanoscale. The objective is to provide readers with an understanding of the essential physics of nanoscale transistors as well as some of the practical technological considerations and fundamental limits. This book is written in a way that is broadly accessible to students with only a very basic knowledge of semiconductor physics and electronic circuits.

-->

Complemented with online lecture by Prof Lundstrom: nanoHUB-U Nanoscale Transistor

Contents:

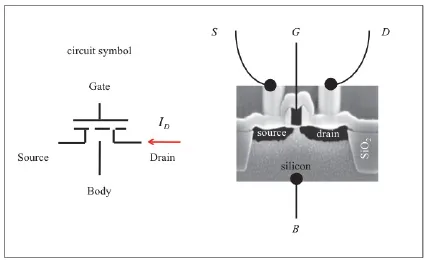

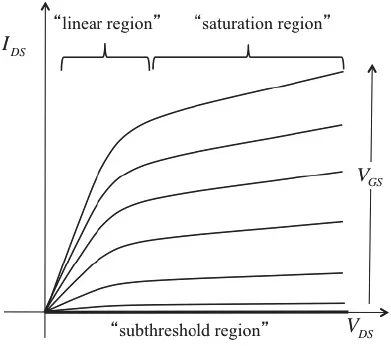

- MOSFET Fundamentals:

- Overview

- The Transistor as a Black Box

- The MOSFET: A Barrier-Controlled Device

- MOSFET IV: Traditional Approach

- MOSFET IV: The Virtual Source Model

- MOS Electrostatics:

- Poisson Equation and the Depletion Approximation

- Gate Voltage and Surface Potential

- Mobile Charge: Bulk MOS

- Mobile Charge: Extremely Thin SOI

- 2D MOS Electrostatics

- The VS Model Revisited

- The Ballistic MOSFET:

- The Landauer Approach to Transport

- The Ballistic MOSFET

- The Ballistic Injection Velocity

- Connecting the Ballistic and VS Models

- Transmission Theory of the MOSFET:

- Carrier Scattering and Transmission

- Transmission Theory of the MOSFET

- Connecting the Transmission and VS Models

- VS Characterization of Transport in Nanotransistors

- Limits and Limitations

--> -->

Readership: Any student and professional with an undergraduate degree in the physical sciences or engineering.

-->Transistors;CMOS;MOSFET;Nanoelectronics Key Features:

- The lectures take a unique approach that is physically insightful, mathematically simple, and that works for nano-devices as well as for micro and macro devices

- The lectures are designed to be broadly accessible to anyone with an undergraduate degree in the physical sciences or engineering

- The lectures are complemented by an extensive set of on-line resources

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

PART 1

MOSFET Fundamentals

Lecture 1

Overview

1.1Introduction

1.2Electronic devices: A very brief history

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Series

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Constants Used in These Lectures

- Some Symbols Used

- Contents

- List of Figures

- PART 1: MOSFET Fundamentals

- PART 2: MOS Electrostatics

- PART 3: The Ballistic MOSFET

- PART 4: Transmission Theory of the MOSFET

- Appendix A Listing of Exercises

- Index