eBook - ePub

Ulsi Front-end Technology: Covering From The First Semiconductor Paper To Cmos Finfet Technology

Covering from the First Semiconductor Paper to CMOS FINFET Technology

- 248 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Ulsi Front-end Technology: Covering From The First Semiconductor Paper To Cmos Finfet Technology

Covering from the First Semiconductor Paper to CMOS FINFET Technology

About this book

-->

The main focus of this book is ULSI front-end technology. It covers from the early history of semiconductor science & technology from 1874 to state-of-the-art FINFET technology in 2016. Some ULSI back-end technology is also covered, for example, the science and technology of MIM capacitors for analog CMOS has been included in this book.

--> Contents:

- Preface

- Author Biography

- Introduction to the History of Semiconductors

- History of MOS Technology

- CMOS Switching Speed Characterization and An Overview Regarding How to Speed Up CMOS

- Low Power CMOS Engineering

- Analog CMOS Technology

- Index

-->

--> Readership: The book is useful for researchers in semiconductor technology especially practicing engineers. -->

Keywords:Semiconductor;Integrated Circuits;CMOS;High Speed;Low Power;Digital;Analog;Mixed-Signal;Planar Technology;FINFET;MIM CapacitorReview: Key Features:

- The book is readable for beginners

- The book is useful for semiconductor technology historians

- The book is useful for practicing engineers

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Ulsi Front-end Technology: Covering From The First Semiconductor Paper To Cmos Finfet Technology by W S Lau in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Technology & Engineering & Electrical Engineering & Telecommunications. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter One

Introduction to the History of Semiconductors

1.1Early History of Semiconductors

According to an article regarding the very early history of semiconductors written by Georg Busch,1 the first person who mentioned something close to the word “semiconductor” was an Italian scientist Alexandro Volta (1745–1827), who was famous for the invention of the electric battery. Volta was born in Como, Lombardy, Italy. However, during his life span, a unified Italy did not exist; Volta was first under the rule of the Emperor of Austria, then under the rule of Napoleon Bonaparte and then under the rule of the Emperor of Austria again. It is interesting to note that Volta published in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, which is the oldest scientific journal in the English-speaking world, in the United Kingdom since 1665. In 1782, Volta published a paper in Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London.2 It was unclear if he wrote his paper in Italian or in French; however, at the end of his paper, an English translation appeared. Inside the English translation, a small passage can be found as follows. “The surface of those bodies does not contract any electricity, or if any electricity adheres to them, it vanishes soon, on account of their semi-conducting nature; for which reason they cannot answer the office of an electrophorus, and therefore are more fit to be used as condensers of electricity.”

Humphry Davy (1778–1829) was a famous UK scientist who served as the President of the Royal Society from 1820–1827. He discovered chlorine and iodine. In 1821, Davy mentioned his observation of the effect of increasing temperature on the electrical conductivity of metals as follows.3 “The most remarkable general result that I obtained by these researches, and which I shall mention first, as it influences all others, was, that the conducting power of metallic bodies varied with the temperature, and was lower in some inverse ratio as the temperature was higher.” Michael Faraday (1791–1867) was an English chemist and physicist. He contributed significantly to the understanding of electromagnetism and electrochemistry. Faraday’s experimental work in chemistry led him to the first documented observation of a material which is now known as a semiconductor. In 1833, he found that the electrical conductivity of silver sulfide increased with increasing temperature as follows.4 “The effect of heat in increasing the conducting power of many substances, especially for electricity of high tension, is well known. I have lately met with an extraordinary case of this kind, for electricity of low tension, or that of the voltaic pile, and which is in direct contrast with the influence of heat upon metallic bodies and decribed by Sir Humphry Davy.” In his 1833 paper, Faraday mentioned Davy’s 1821 paper. In fact, Michael Faraday once served as Davy’s assistant. “The substance presenting this effect is suphuret of silver. It was made by fusing a mixture of precipitated silver and sublimed sulphur, removing the film of silver by a file from the exterior of the fused mass, pulverizing the sulphuret, mingling it with more sulphur, and fusing it again in a green glass tube, so that no air should obtain access during the process. The surface of the sulphuret being again removed by a file or knife, it was considered quite free from uncombined siliver.” For a metal, the electrical conductivity decreases with increasing temperature. Sulphuret of silver is now known as silver sulfide (Ag2S), which is a direct bandgap semiconductor with a bandgap of about 1 eV.5 Thus this effect usually found in semiconductors, is opposite to the situation usually found for metals.

With the help of modern physics, we can easily see that raising the temperature of most semiconductors increases the density of free carriers (electrons or holes) inside them and hence their conductivity. This effect can be exploited to make thermistors whose resistance is sensitive to a change in temperature. For metals, the density of free carriers (electrons) is not influenced by a higher temperature; however, a higher temperature implies stronger scattering and thus lower electron mobility. For semiconductors, a higher temperature also implies stronger scattering and thus lower electron mobility but the increase in carrier density due to higher temperature can be the stronger and thus the dominant effect. Thus Faraday’s 1833 paper can be considered as the first scientific paper loosely related to semiconductor physics.

For semiconductors, the behavior of an extrinsic semiconductor (a semiconductor doped by a shallow donor or acceptor) is similar to that of metals reported by Davy; however, the behavior of an intrinsic semiconductor (for example, an undoped semiconductor) is similar to that of silver sulfide reported by Faraday. Thus a resistor made of an extrinsic semiconductor can show up a positive temperature coefficient of resistance while a resistor made of an intrinsic semiconductor can show up a negative temperature coefficient of resistance.

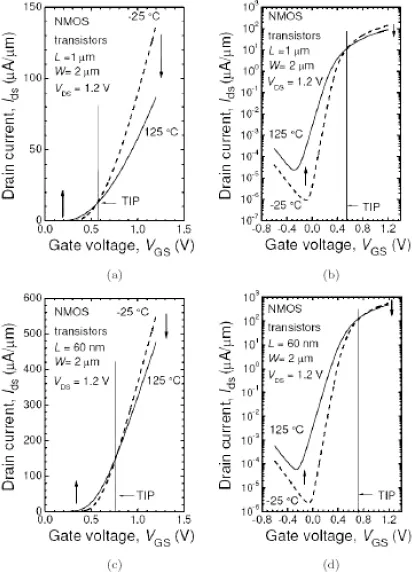

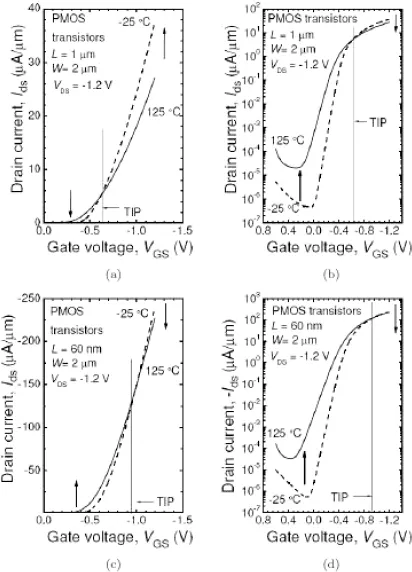

For modern MOS transistors, the carrier mobility involves 3 scattering mechanisms: Coulombic scattering, phonon scattering and surface roughness scattering. All 3 scattering mechanisms become stronger at higher temperature, resulting in lower mobility at higher temperature.6 For modern MOS transistors, the on current decreases with increasing temperature just like Davy’s report while the off current increases with increasing temperature in a way similar to an intrinsic semiconductor and thus similar to Faraday’s observation. An interesting phenomenon is that for MOS transistors there exists a cross-over point where the current is insensitive to temperature variation.7–11 As shown in Fig. 1.1, the drain current versus gate voltage characteristics of an n-channel MOS transistor show up a TIP at a particular value of gate voltage. TIP stands for “temperature independent point”. For gate voltage above TIP, the drain current decreases with temperature. For gate voltage below TIP, the drain current increases with temperature. Similarly, as shown in Fig. 1.2, the drain current versus gate voltage characteristics of a p-channel MOS transistor show up a TIP at a particular value of gate voltage. Thus a resistor made up of the drain and source electrodes of an MOS transistor with a fixed gate-to-source voltage can show up a positive temperature coefficient of resistance above TIP and a negative temperature coefficient of resistance below TIP, respectively. Another conclusion can be drawn from Fig. 1.1 and Fig. 1.2: operation of MOS transistors at low temperature implies higher on current and lower off current; the implication is that MOS technology usually improves by a decrease in operation temperature. For example, carbon nanotube (CNT) technology has been shown that device operation is possible. However, manufacturability of CNT devices is doubtful. CNT is known to have high thermal conductivity. Packaging technology using CNT may be useful to lower the actual operation temperature of an MOS integrated circuit housed in a package, resulting in better performance. More discussion can be found in Chapter 3 and Chapter 4.

Fig. 1.1 Effects of temperature on the on-state current (/on) and off-state current (/off) of NMOS transistor according to Yang et al.a,11

Fig. 1.2 Effects of temperature on the on-state current (/on) and off-state current (/off) of PMOS transistor according to Yang et al.a,11

A French scientist Alexandre-Edmond Becquerel (1820–1891) discovered the photovoltaic effect, which is the physics behind the solar cell, 1839.12 He published his discovery in Comptes Rendus, which is a French scientific journal published by the French Academy of Sciences since 1835. He was the son of Antoine César Becquerel, who was a French scientist pioneering in the study of electric and luminescent phenomena, and the father of Henri Becquerel who was the more famous French scientist and the winner of the 1903 Nobel Prize in Physics for discovering radioactivity.

The effect observed by Alexandre-Edmond Becquerel in 1839 was via an electrode in a conductive solution exposed to light. The device is now known as a photoelectrochemical solar cell. There can be other names for the same device, for example, a semiconductor liquid junction solar cell. There exist quite some review papers on this subject.13,14 The key point is that there must be a semiconductor present. There is an electrolyte. It can be in the form of a solution or in the form of a molten solid. The electrolyte is forming a junction with a semiconductor. There are two metal electrodes connecting to the electrolyte and the semiconductor respectively. The semiconductor involved in Becquerel’s 1839 report is not clear. Many years later in 1873, Willoughby Smith found that selenium is photoconductive.15 W.G. Adams (William Grylls Adams, 1836–1915) and R. E. Day (Richard Evans Day, student of Adams) observed the photovoltaic effect in selenium without involving any liquid and reported their observation in 1877.16 The American Charles Fritts developed a solar cell using selenium with a thin layer of gold in 1883.17 Thus selenium may be considered the first semiconductor in the solid state discovered by mankind. However at that time both Becquerel and Smith did not know semiconductor physics and thus could not really explain what actually happened.

Photoconductivity is just the formation of free electrons and free holes because light can raise an electron from the valence band to the conduction band leaving behind a hole. It takes many years for the physics of the photovoltaic effect to be understood. Kurt Lehovec (1918–2012) may be the first scientist who can claim that he managed to explain the photovoltaic effect in 1948. Lehovec was born in 1918 in Ledvice, northern Bohemia, Austria-Hungary just a few months before the end of World War I. After the end of World War I in November 1918, Austria-Hungary broke up into several countries. One of these new countries was known as Czechoslovakia with Prague as its capital. According to his own website (www.kurtlehovec.com), after he graduated from high school in 1936, he moved to Prague, where he attended university and received his PhD in Physics in 1941. However, Czechoslovakia was annexed by Nazi Germany in the period of 1938–1939 and Kurt Lehovec became involved in the history of Germany. (Note: Lehovec’s website is no longer available after his death in 2012.) At the end of World War II, he spent the next two years in postwar West Germany, continuing with theoretical research and came up with the explanation of the solar cell effect. The US Signal Corps had become aware of his discovery at Prague, and invited him in the summer of 1947 to the USA under the Project Paperclip fo...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Halftitle

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Preface

- Author Biography

- Chapter One. Introduction to the History of Semiconductors

- Chapter Two. History of MOS Technology

- Chapter Three. CMOS Switching Speed Characterization and An Overview Regarding How to Speed Up CMOS

- Chapter Four. Low Power CMOS Engineering

- Chapter Five. Analog CMOS Technology

- Index