![]()

Chapter 1

Early Episodes

Peter Brimblecombe

School of Energy and Environment, City University

of Hong Kong, Hong Kong

1.1Introduction

Air pollution has been experienced throughout human history. It is hardly surprising that our ancestors would have been exposed to dust, pollen and smoke from forest fires. Pollution has been regulated since ancient times as humans gathered in cities, and records of environmental pollution and degradation begin to be more abundant from the classical period (Hughes, 1994). In the ancient world, air pollution episodes that were lengthy and geographically extensive are more likely to have been natural in origin. Nevertheless, it is still possible to trace some episodes of human origin from such early times and follow them through much of our history. This account will end at the beginning of the 20th century, because by this point measurements and detailed scientific studies were available and change the nature of the evidence.

1.2Ancient Egypt, Greece and Rome

Perhaps familiar, but sometimes seeming not to be part of our view of urban air quality, is odour. It was rife in cities of the past where small piles of dung and rubbish were widespread. There is an example of this type of air pollution from putrefaction in Egypt that was claimed to have serious outcomes. The Kushite King Piye (reigned ~741 to ~712 BC), founder of the 25th Dynasty, was responsible for expanding Nubian power into Lower Egypt and ultimately extended this control as far as the Nile Delta. He laid siege to a number of Egyptian towns including the siege of Hermopolis, which Lichtheim (2006) places at about 734 BC, and is described on The Victory Stele of Piye. The fate of the city is revealed: “Days passed and Ur [Hermopolis] was a stench to the nose for lack of air to breathe. Then Ur threw itself on its belly, to plead before the king.” It is hard to interpret this, but one can only presume that the stench of rotting corpses and other organic matter made continued occupation within the city intolerable.

The problem of odour was important to regulate in ancient cities. In ancient Athens, there were:

“… ten City Commissioners (Astynomi), of whom five hold office in Piraeus and five in the city. Their duty is to see that …. no collector of sewage shall shoot any of his sewage within ten stradia [possibly a stadion so this distance would be ~10*185 m] of the walls; they prevent people from blocking up the streets by building, or stretching barriers across them, or making drain-pipes in mid-air with a discharge into the street, or having doors which open outwards; they also remove the corpses of those who die in the streets”

Aristotle, The Athenian Constitution

Translated by Sir Frederic G. Kenyon

The Roman Governor of Britain, Sextus Julius Frontinus, was later appointed Curator Aquarum to Rome. He improved Rome’s water supply, and argued in his book De aquis urbis Romae, presumably through a miasmatic connection, that he also reduced the effects of the city’s “infamis aer … [or] gravioris caeli …” through proper administration of Rome’s aqueducts. In the Middle East, there were related pollution problems in classical Judea where the Mishnah Laws demanded that polluting sources be more than 50 cubits (~25 m) from a neighbour’s residence. In the case of tanneries, the prevailing wind ought to be considered (Mamane, 1987) and a preoccupation with organic contaminants continued in the Islamic world (Gari, 1987).

More regular forms of pollution, such as those from smoke, appear in later classical references. Relatively few solutions were available to solve industrial air pollution problems, but the idea of zoning was apparent, and in Rome glass making was moved to the suburbs to limit the impact of its smoke. Rural areas of Spain and the Pyrenees had a great deal of mining, and “furnaces for silver are constructed lofty, in order that the vapour, which is dense and pestilent, may be raised and carried off ” (Hamilton and Falconer, 1854).

In Imperial Rome nuisance laws, which treated issues of neighbourly responsibility in cities (urban servitudes), dealt with smoke as though it was water (Brimblecombe, 1987a) arguing: you could no more let water drain across a house than smoke. In Jerusalem, kilns and furnaces were not allowed in the city, to avoid soiling of the walls and buildings (Mamane, 1987). We find a parallel concern in the writings of the Roman poet Horace, which mention the blackening of temples in the ancient city.

“Your fathers’ guilt you still must pay,

Till, Roman, you restore each shrine,

Each temple, mouldering in decay,

And smoke-grimed statue, scarce divine”

Horace, Odes and Carmen Saeculare

Some of the best evidence of early exposure to air pollutants comes from human remains, but this is most likely due to indoor air pollution. Exposure to wind-blown sand and indoor smoke was widespread in the ancient past. Evidence of anthracosis from the deposition of smoke in the lung, and silicosis from fine sand particles is found in mummified tissue (Aufderheide, 2003). Capasso (2000) has argued that lesions found on the ribs of victims of the eruption of Vesuvius suggest that pleurisy was common in Roman times, and this may be evidence of indoor pollution from burning vegetable matter lamp oils. Air pollution seems to have contributed to the poor health of a child from Imperial Rome of the second century, with the mummified body showing evidence of severe anthracosis (Scheidel, 2009). There is skeletal evidence of increased incidence of sinusitis, due to indoor exposure to smoke, in populations from Britain (Wells, 1977). The is some evidence that women were affected more than men, perhaps because they spent more time at the fireplace (Panhuysen et al., 1997), and rural communities seem less affected than those in urban areas (Roberts, 2007). Poor ventilation or the lack of chimneys may have increased the levels of indoor air pollution and sinusitis, as found in Viking communities (Sundman and Kjellström, 2013; Christensen and Ryhl-Svendsen, 2015).

1.3Medieval Period

As with ancient Rome, wood-burning industrial activities could create a serious air pollution problem. The north German city of Lüneburg was renowned for its salt-making in the medieval and early modern periods. Solar evaporation is inefficient so far north, so brines extracted from beneath the city were heated in lead and ceramic pans to increase the concentration and allow salt to crystallise. Salt was a key driver of the city’s wealth from the late 1200s. Across the active period of production between 1554 and 1614 the mean annual output was 21 ktonnes. During the 15th and 16th centuries, the salt-works consumed between 48,000 and 72,000 cm3 of wood each year (Lamschus, 1993; Witthöft, 1989). The salt-works thus generated a large amount air pollution (Brimblecombe, 2011), as shown by the smoke cloud in an early woodcut of the town (Fig. 1.1).

The medieval period is especially interesting, because not only did industrial intensity grow, but also the use of coal became important, most notably in London. Coal was probably used in small quantities in Roman Britain, as it has been frequently found at archaeological sites (Dearne and Branigan, 1995; Smith, 1997). However, literary evidence for its use in classical times is limited and difficult to interpret (Dearne and Branigan, 1995). It is clear though by the 12th century it was used as a fuel in the north of Britain, and in the following century imported into London, where shortages of wood as a fuel led to its increasing use, particularly in lime-burning and metallurgical activities. The lack of chimneys in most dwellings restricted its widespread use as a domestic fuel until the late 1500s.

Fig. 1.1. Smoke from the salt-works close to the now vanished church of St Lambert’s at Lüneburg in the 16th century, from a woodcut of Sebastian Munster (1550) that appears in Braun and Hogenberg’s Civitates Orbis Terrarum (1572).

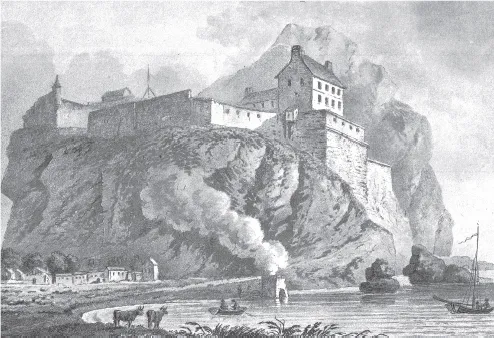

The use of coal may have risen sharply in the 1280s and set the scene for some of the earliest air pollution episodes that warranted investigation by civic authorities. Wood prices increased in the late 13th century and pressured some industries to shift to coal (Brimblecombe, 1975, 1987b). The new fuel was probably not only cheap, but also convenient; especially for kilns used in making lime mortar from calcium carbonate, as these needed to operate at high temperatures. In rural areas, these kilns did not have tall chimneys as late as the 19th century (see Fig. 1.2). Thus, the pollutants, most notably smoke and sulphur dioxide, were released into the atmosphere almost at ground level. Often the quantities of coal used were large; deliveries in excess of 100 tonnes are known from the medieval period. In London, coal was delivered via the lost Fleet River (now Fleet Street) to the west of the city, and adjacent to nearby Old Seacoal Lane and Limburner Lane. These locations are upwind (i.e. the prevailing wind came from the west) of important places in medieval London, such as Smithfield Market and St Paul’s Cathedral. Therefore, the smoke would have created great annoyance, especially as people believed that disease arose from strange smells or noxious airs (miasmatic theory). The coal smoke problem was serious enough to cause complaints in 1285 (and again in 1288). A relevant document reads:

Fig. 1.2. Smoke from a lime kiln at Dumbarton rock and castle on the banks of the River Clyde from Stoddart, John (1800), Remarks on Local Scenery and Manners in Scotland. William Miller: London. Note the low emission height.

“Commission to Roger de Northwode, John de Cobbeham and Henry le Galeys to enquire touching certain lime-kilns (rogis calcis) constructed in the city and suburb of London and at Suthwerk, of which it is complained that whereas formerly the lime used to be burnt with wood, it is now burnt with sea-coal, whereby the air is infected and corrupted to the peril of those frequenting and dwelling in those parts. In executing this commission they are to associate with themselves the mayor and sheriffs of London and the bailiffs of Suthwerk”

Calendar of Patent Rolls 13 Edward I — membrane 18d

This medieval record confirms the fuel and the type of industry, and asserts the reason for concern was health. A later document stresses the need to find remedies for the problem. Frustration was evident by the next century, when the use of coal was banned. Penalties for contravening air pollution regulations seem to have been fines or the removal of the offending kiln; a much-discussed case of an execution seems unlikely to have occurred (Brimblecombe, 1976). The ban on coal was apparently difficult to enforce in the long term, as by 1329 a Newcastle collier, Hugh de Hencham was making lime in London, presumably with coal as a fuel (Brimblecombe, 1975).

As in the classical Mediterranean, solutions to the air pollution problem were limited. Evidently, the initial response from officials, although not really a solution, was simply to ban the use of coal. Additionally, there is some evidence that chimney heights may have been specified in London as shown by a case brought before the London Assize of Nuisance in 1377. Here, it was argued that the offending chimney was 12 feet lower than was good practice. Furthermore, there are records indicating that some blacksmiths thought it would be wise to burn coal only during the day (Brimblecombe, 1976, 1987a), perhaps when the air was more turbulent and wind speeds greater.

The advent of the Black Death caused a decrease in the European population in the mid-14th century. This tended to cause a shortage of labour and an increase in wages. Such economic changes may have helped maintain wood as the preferred, but more expensive fuel. The wider incorporation of chimneys into houses made coal more acceptable as a domestic fuel in London by the late 1500s. Thus, the 17th century saw it become the predominant fuel, with more than a million tonnes imported each year into London towards the end of the century (Brimblecombe, 1978; Hausman, 1980).

1.4Early Scientific Interest

The 17th century also saw a growing interest in scientific discovery, and there were a number of academic papers on air pollution and its impact. In particular, early members of the Royal Society, such as Boyle, Digby, Evely...