Stock Market Crashes

Predictable and Unpredictable and What to do About Them

- 308 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Stock Market Crashes

Predictable and Unpredictable and What to do About Them

About this book

-->

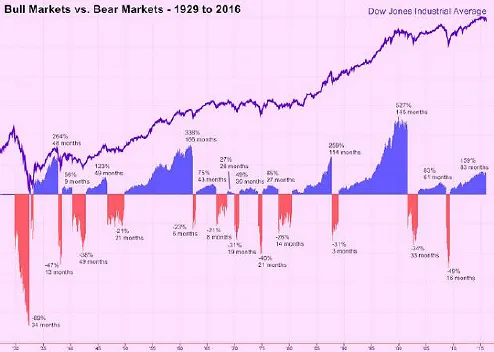

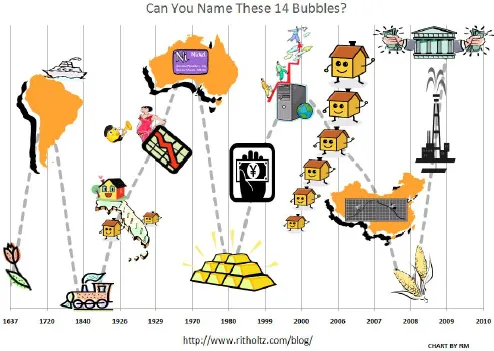

This book presents studies of stock market crashes big and small that occur from bubbles bursting or other reasons. By a bubble we mean that prices are rising just because they are rising and that prices exceed fundamental values. A bubble can be a large rise in prices followed by a steep fall. The focus is on determining if a bubble actually exists, on models to predict stock market declines in bubble-like markets and exit strategies from these bubble-like markets. We list historical great bubbles of various markets over hundreds of years.

We present four models that have been successful in predicting large stock market declines of ten percent plus that average about minus twenty-five percent. The bond stock earnings yield difference model was based on the 1987 US crash where the S&P 500 futures fell 29% in one day. The model is based on earnings yields relative to interest rates. When interest rates become too high relative to earnings, there almost always is a decline in four to twelve months. The initial out of sample test was on the Japanese stock market from 1948-88. There all twelve danger signals produced correct decline signals. But there were eight other ten percent plus declines that occurred for other reasons. Then the model called the 1990 Japan huge -56% decline. We show various later applications of the model to US stock declines such as in 2000 and 2007 and to the Chinese stock market. We also compare the model with high price earnings decline predictions over a sixty year period in the US. We show that over twenty year periods that have high returns they all start with low price earnings ratios and end with high ratios. High price earnings models have predictive value and the BSEYD models predict even better. Other large decline prediction models are call option prices exceeding put prices, Warren Buffett's value of the stock market to the value of the economy adjusted using BSEYD ideas and the value of Sotheby's stock. Investors expect more declines than actually occur. We present research on the positive effects of FOMC meetings and small cap dominance with Democratic Presidents. Marty Zweig was a wall street legend while he was alive. We discuss his methods for stock market predictability using momentum and FED actions. These helped him become the leading analyst and we show that his ideas still give useful predictions in 2016-2017. We study small declines in the five to fifteen percent range that are either not expected or are expected but when is not clear. For these we present methods to deal with these situations.

The last four January-February 2016, Brexit, Trump and French elections are analzyed using simple volatility-S&P 500 graphs. Another very important issue is can you exit bubble-like markets at favorable prices. We use a stopping rule model that gives very good exit results. This is applied successfully to Apple computer stock in 2012, the Nasdaq 100 in 2000, the Japanese stock and golf course membership prices, the US stock market in 1929 and 1987 and other markets. We also show how to incorporate predictive models into stochastic investment models.

--> Contents:

- Introduction

- Discovery of the Bond–Stock Earnings Yield Differential Model

- Prediction of the 2007–2009 Stock Market Crashes in the US, China and Iceland

- The High Price–Earnings Stock Market Danger Approach of Campbell and Shiller versus the BSEYD Model

- Other Prediction Models for the Big Crashes Averaging –25%

- Effect of Fed Meetings and Small-Cap Dominance

- Using Zweig's Monetary and Momentum Models in the Modern Era

- Analysis and Possible Prediction of Declines in the –5% to –15% Range

- A Stopping Rule Model for Exiting Bubble-like Markets with Applications

- A Simple Procedure to Incorporate Predictive Models in Stochastic Investment Models

- Appendices:

- Other Bubble-testing Methodologies and Historical Bubbles

- Mathematics of the Changepoint Detection Model

-->

--> Readership: Students, researchers and the general public who are interested to understand more about stock market crashes and what to do about them. -->

Keywords:Stock Market Crashes;Brexit;Trump;Financial BubblesReview:0

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

| LARGEST ONE DAY DROPS EVER FOR THE S&P500. OCTOBER IS WELL REPRESENTED | ||

| Date | S&P500 | Change |

| 19/10/87 | 224.84 | −20.5% |

| 28/10/29 | 22.74 | − 12.9% |

| 29/10/29 | 20.43 | − 10.2% |

| 5/11/29 | 20.61 | − 9.9% |

| 18/10/37 | 10.76 | − 9.1% |

| 5/10/31 | 8.82 | − 9.1% |

| 15/10/08 | 907.84 | − 9.0% |

| 1/12/08 | 816.21 | − 8.9% |

| 20/7/33 | 16.57 | − 8.9% |

| 29/9/08 | 1106.39 | −8.8% |

Probability = ______ %.)

Table of contents

- Cover

- Halftitle

- Series Editors

- Title

- Copyright

- Review Quotes

- Dedication

- Preface

- About the Authors

- Contents

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Discovery of the Bond–Stock Earnings Yield Differential Model

- 3. Prediction of the 2007–2009 Stock Market Crashes in the US, China and Iceland

- 4. The High Price–Earnings Stock Market Danger Approach of Campbell and Shiller versus the BSEYD Model

- 5. Other Prediction Models for the Big Crashes Averaging−25%

- 6. Effect of Fed Meetings and Small-Cap Dominance

- 7. Using Zweig’s Monetary and Momentum Models in the Modern Era

- 8. Analysis and Possible Prediction of Declines in the −5% to −15% Range

- 9. A Stopping Rule Model for Exiting Bubble-like Markets with Applications

- 10. A Simple Procedure to Incorporate Predictive Models in Stochastic Investment Models

- Appendix A. Other Bubble-testing Methodologies and Historical Bubbles

- Appendix B. Mathematics of the Changepoint Detection Model

- Bibliography

- Index