![]()

Chapter 1

Introduction

Irish economist Richard Cantillon (1680–1734) defined the French word entrepreneur as a person taking the risk to work for oneself (Cantillon, 1755). This includes the vendor at an impromptu stall and the organ grinder (Exhibit 1.1).

An aristocrat industrialist, and French economist, Jean-Baptiste Say (1767–1832) defined the entrepreneur as the agent who “unites all means of production and who finds in the value of the products ... the re-establishment of the entire capital he employs, and the value of the wages, the interest, and the rent which he pays, as well as the profits belonging to himself” (1816, pp. 28–29). Fraser (1937) associated entrepreneurs with the management of a business unit, profit taking, business innovation and uncertainty bearing. Belshaw argued, “an entrepreneur is someone who takes the initiative in administering resources. He is probably not an entrepreneur unless he does undertake ordinary management tasks” (1955, p. 147). Casson elaborated, “an entrepreneur is someone who specializes in taking judgemental decisions about the coordination of scarce resources” (1982, p. 10).

Gartner (1989) defined entrepreneurship as the creation of new organisations. The Gartner (1990) Delphi study linked entrepreneurship to individuals with unique personality characteristics and abilities.

Others focused on innovation. Schumpeter wrote, “The carrying out of new combinations we call ‘enterprise’; the individuals whose function it is to carry them out we call ‘entrepreneurs’” (1934, p. 74). Scase and Goffee explained, “They are seen as risk-takers and innovators who reject the relative security of employment in large organisations to create wealth and accumulate wealth” (1987, p. 1). Given that Schumpeterian innovators are relatively few, this book accepts the notion that small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) comprise the more common flagship of entrepreneurship — as described by Cantillon (1755) — in the broadest sense.

Exhibit 1.1 Vendors and organ grinder; photo © 2017 Léo-Paul Dana.

Based on the classical definition of the word entrepreneurship, which can be traced to the German Unternehmung (literally: undertaking) and to the French entreprendre (literally: between taking), in this book, the word entrepreneur refers to “an individual who earns his livelihood by exercising some control over the means of production and produces more than he can consume in order to sell (or exchange) it for ... income” (Dana, 1995a, pp. 57–58). Therefore, in this volume, the word entrepreneur includes the self-employed, as well as the founder or current owner of a business entity, usually a small or medium firm and sometimes a large one.

There are also different definitions of SMEs. In Australia, small firms have fewer than 20 employees, except small manufacturers, which have up to 99. In Canada, a small service firm has up to 49 employees, while a small manufacturer may have up to 499. In Japan, a firm with up to 250 employees is deemed to be small. In the United States, a small business may have up to 500 employees.

Prior to standardisation, different countries within Europe had diverse definitions: In Italy, a microenterprise could have up to 100 employees while a small enterprise had 101–300 employees. In the Netherlands, a business with nine or fewer employees was a small enterprise, while 10 or more constituted a medium-sized firm. In Portugal, a medium enterprise required 100 or more employees, while in Spain it was at least 500. In Sweden the term SME applied to firms with fewer than 200 employees.

Until 1996, the European Union defined an SME as having fewer than 500 employees. In April 1996, the European Commission adopted the following definitions:

- SMEs are independent firms with fewer than 250 employees and have either an annual turnover not exceeding ECU1 40 million, or a balance sheet total not exceeding ECU 27 million.

- The small enterprise has fewer than 50 employees and has either an annual turnover not exceeding ECU 7 million or an annual balance-sheet total not exceeding ECU 5 million and conforms to criterion of independence.

- Independent enterprises are those which are not owned, as to 25% or more of the capital or the voting rights are held by one enterprise, or jointly by several enterprises, falling outside the definition of an SME or a small enterprise, whichever may apply.2

Among several later definitions, SMEs were defined as independent firms (i.e., other companies’ share of ownership could not exceed 25%), with fewer than 250 employees, and annual sales not exceeding 20,000,000 euro.

Since January 1, 2005, an enterprise is officially considered to be any entity engaged in an economic activity, irrespective of its legal form. This includes, the self-employed as well as family businesses, partnerships and associations that are regularly engaged in an economic activity. European Commission definitions have been as follows:

- Microenterprises are firms with up to nine full-time-equivalent employees — including owner–managers — and whose annual turnover or annual balance sheet is below 2,000,000 euro.

- Small businesses have between 11 and 49 employees inclusively, and sales of up to 10,000,000 euro.

- Medium-sized enterprises have 50, and up to 250 employees, with sales not exceeding 50,000,000 euro and an annual balance sheet not exceeding 43,000,000 euro.

The Context

“Entrepreneurship was born in Europe” (Fayolle, Kyrö, and Ulijn, 2005, p. 4). In fact, the concept of the entrepreneur first appeared in 1437, in a French dictionary (Landström, 1999). Pioneers of entrepreneurship theory include Cantillon (1755) and Mill (1848), both Europeans. Entrepreneurship as a social science came to America later, with great minds like Ely and Hess (1893, p. 95). From a pedagogical perspective, Groen, Ulijn, and Fayolle (2006) suggested that entrepreneurship has been so far very much an American concept; nevertheless, entrepreneurship in Europe has been gaining importance, as is the small business sector. According to Mugler (1998), the renaissance of the small business sector in Europe has been a spill-over of the sector’s revival initiated in the United States.

Reynolds (1997) noted that the expansion of markets has not been associated with an expanded role for larger firms; instead, smaller firms are filling niche roles (Buckley, 1997; Malaise, 1988). Fotopoulos and Spence (1998) suggested that small firms use survival strategies and overcome barriers to entry, and Kemp and Lutz (2006) found that microfirms perceive lower barriers to entry than medium-sized and large businesses. In fact, society needs SMEs to undertake functions that multinationals do not do because of the opportunity cost involved. SMEs often excel in niche markets. The European Charter for Small Enterprises, adopted by the General Affairs Council, recognised small firms as the backbone of the European economy.

The purpose of this book is to provide an introduction to entrepreneurship in countries of Western Europe. As discussed by Kaynak and Jallat, this “will necessitate consideration of the broader social, cultural, and legal-political systems” (2004, p. 5). History will be emphasised because, “Progress, far from consisting in change, depends on retentiveness. When change is absolute there remains no being to improve and no direction is set for possible improvement ... Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it” (Santayana, 1905, Volume 1, p. 284).

Bamford (1987) suggested that SMEs are strongly shaped by historical factors. History shapes countries — and countries shape the environment for entrepreneurship. The Armistice signed November 11, 1918 brought a truce to the Great War (World War I), but it was the Treaty of Versailles of 1919 that fixed new borders. World War II and events in the Balkans further changed the map of Europe. Political entities are born; they grow and shrink, but they do not always correspond to nations — people sharing a culture, language, and entrepreneurial outlook.

Over the years, economic power has shifted across Europe. Sombart noted, “One of the most important facts in the growth of modern economic life is the removal of the centre of economic activity from the nations of Southern Europe — the Italians, Spaniards, and Portuguese, with whom must be reckoned some South German lands — to those of the North-West — the Dutch, the French, the English and the North Germans” (1913, p. 11).

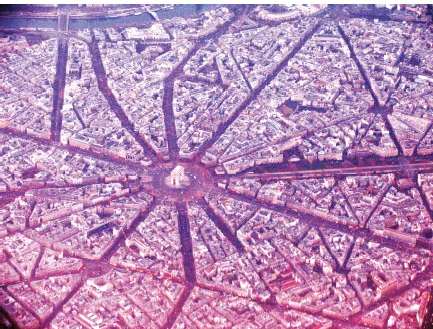

Indeed, Europe has a very rich history, including important wars as well as prosperous times of peace. In Paris, the Arc de Triomphe (Exhibit 1.2) is a reminder of Napoleon’s victories. In some countries, including France, the 11th of November is a legal holiday, ever since 1919 (see Exhibit 1.3).

In 1944, Belgium, the Netherlands and Luxembourg entered the Benelux customs union. In 1951, Belgium, France, the Federal Republic of Germany, Italy, Luxembourg and the Netherlands signed the Treaty of Paris creating the European Coal and Steel Community.

Exhibit 1.2 The Arc de Triomphe at sunrise; photo © 2017 Léo-Paul Dana.

Exhibit 1.3 Remembering the fallen; photo © 2017 Léo-Paul Dana.

Although a Scandinavian customs union proposed in 1947 was rejected, in 1952, the Nordic Council was established by Denmark, Iceland, Norway and Sweden, for cooperation between these countries and in 1954 its members agreed to a common labour market; in 1955, Finland joined. The 1957 Treaty of Rome came into effect on January 1, 1958, establishing the European Common Market (later the European Economic Community), uniting Belgium, France, the Federal Republic of Germany, Italy, Luxembourg and the Netherlands.

In 1959, the Stockholm convention established the European Free Trade Association (EFTA), allowing Austria, Iceland, Norway, Sweden, and Switzerland to maintain different external tariffs while eliminating internal tariffs on industrial products originating within the free trade area. Finland joined EFTA in 1961.

In 1973, the European Economic Community welcomed the Kingdom of Denmark, the Republic of Ireland and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland. Greece joined in 1981, followed by Portugal and Spain in 1986. In 1989, the Council of Ministers of the European Economic Community adopted the decision to make SMEs a priority. This included the creation of a favourable environment with limited regulation, the encouragement of new venture creation and the establishment of R&D priorities.

In 1991, the Maastricht Treaty laid the foundation for an Economic and Monetary Union (EMU). In 1993, the Single European Act created a European Union allowing free movement of goods, services, capital and labour. At the time there were 17 million privately owned enterprises in the non-primary sector of the European Union, of which 93.3% were microfirms, 6.2% were small, 0.5% were medium, and 0.1% were large (Mulhern, 1995).

Potts argued that the concept of a single European market was supported by, “to be accurate, big business more than small business” (2000, p. 322). In 1995, the European Union grew with the entry of three former members of EFTA, namely Austria, Finland, and Sweden.

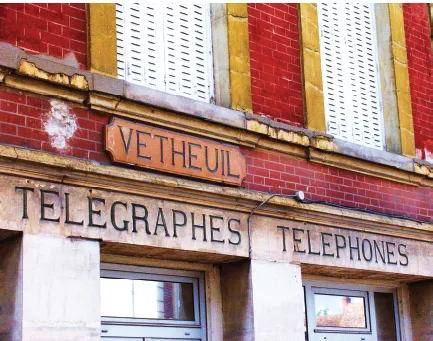

Until the 20th century, there were huge discrepancies in infrastructure and technology across Europe. In Portugal, telecommunications development relied on the Anglo Portuguese Telephone Company (see Chapter 18 in this volume). In France, the government funded the Postes Telegraphes Telephones (PTT), which facilitated business. Exhibit 1.4 features the PTT of Vétheuil, a village in the area of which Claude Oscar Monet (1840–1926) painted 26 scenes.

Recent years have witnessed the spread of technology. Another trend across Europe has been for former colonisers to give various levels of autonomy including independence to territories overseas. In 2009, Denmark granted Greenland (see Exhibit 1.5) the right to have self-rule.

Exhibit 1.4 PTT in Vétheuil; photo © 2017 Léo-Paul Dana.

At the macro-economic level, Europe has been experiencing convergence; technology, for instance, is becoming increasingly similar in different countries. At the micro-level, however, Europeans from different regions are maintaining cultural uniqueness. In the words of McCall, “There are many more nations in the world than there are states for them” (1980, pp. 538–539). As observed by Berlinski, “Unsurprisingly, it is difficult to cobble nation-states together into a grand transnational entity” (2005, p. A-17).

Entrepreneurship is also maintaining its regional characteristics, but co-operation, networking, and clustering into industrial agglomerations (Baptista and Swann, 1998; Glassman and Voelzkow, 2001) has gained importanc...