![]()

Part I

Western Secular Stagnation and Social Strife

![]()

Chapter 1

Overreach and Discord

Steven Rosefielde

The Industrial Revolution catapulted the West to the top of the heap, inspiring dreams of global dominion, despite a series of devastating world wars and a 73-year ideological death dance between Soviet communism and Western capitalism. Over the centuries, the West gradually forged a coherent idealist agenda (“American Dream”) founded on the principles of reason, democracy, private property, free enterprise, liberty, humanitarianism, social justice, and the rule of law.

The dissolution of the Soviet Union on December 25, 1991, appeared to clear the way for the West to transform the world in its own likeness (Fukuyama 2006). The movement seemed to be succeeding with unstoppable momentum spearheaded by North Atlantic Treaty Organization’s and the European Union’s eastward march and soft power more broadly between 1991 and 2008, but supremacy did not endure. The one-two punch of the global financial crisis of 2008 and post-crisis economic stagnation sent the West reeling. The Washington consensus went the way of the dodo. A simmering social–economic–political and cultural crisis exacerbated by wealth inequality, Islamic immigration, and a deluge of refugees came to a boil. Russia’s annexation of Crimea, China’s provocative actions in the South China Sea, the emergence of the ISIS Middle East challenge, terrorism, the Syrian imbroglio, Iran’s machinations, and nuclear proliferation further savaged the West’s aura of inevitability. Suddenly, it became a stretch to imagine a unipolar reality where the idea of the West becomes the World’s idea.

The new reality is multipolar, including America, Britain, the EU, Russia, China, and other great powers. While America can console itself as primus inter pares and the EU is affluent, there no longer seems any prospect for a second Western unipolar moment. The West appears increasingly militarily, economically, politically, and socially vulnerable. The old Western imperial dream of cloning the world in its own image is dead, and Russia, China, Iran, and the ISIS appear capable of expanding their spheres of influence and even augmenting their territories at the West’s expense.

Western leaders, including Donald Trump, know that the correlation of forces has taken a nasty turn but cannot muster their resolve, while Russian and Chinese leaders rub their eyes in disbelief. There is time to right the ship. Trump is committed to trying in some important respects. He will restore American naval forces to the 1992 level and significantly increase military preparedness. He is committed to reinvigorating the economy by shifting to a government regulatory regime that incentivizes entrepreneurship, innovation, and growth and reduces anti-productive influences. His proposed adjustments are not panaceas and will not restore America’s (the West’s) unipolarity. America, however, should be able to hold its own in Trump’s brave new world. It should be able to prosper and peacefully coexist with Russia and China, while containing them.

Reference

Fukuyama, Francis (2006), End of History and the Last Man Standing, New York: Free Press.

![]()

Chapter 2

Europhoria

Bruno Dallago

After years of euphoria for the common currency (“europhoria”), a deepening and broadening fault line is growing in the Eurozone between vulnerable and resilient countries.1 The fault line became evident with the 2008 crisis, although its causes had been preexistent to it and predominantly internal to the Eurozone. Policies and common procedures are strengthening the financial situation of resilient countries, while the negative effect of austerity policies and the difficulty of vulnerable countries in reforming their economies are weakening their position. The latter are meeting increasing costs and weakening their performance, without the former being advantaged proportionally in a negative sum game. The Eurozone is consequently ailing and splitting, to the dissatisfaction and disadvantage of its inhabitants and economic agents.

While all countries apparently are greatly supporting their participation in the common currency and some of them are undergoing serious sacrifices imposed upon their population in order to comply with the common rules and requirements, the Eurozone seems to be unable to get out of a clearly undesirable and even dangerous situation. Anti-euro political parties and movements are slowly, but safely, becoming more popular and vociferous. The perspective of “Brexit,” i.e., the exit of an important member country from the European Union (EU) — but not the Eurozone of which it was not part — dramatically strengthened such negative sentiments in the short run. However, the difficulties that the British polity and economy are meeting after the June 23, 2016, referendum and the opposition to Brexit by Scotland and Northern Ireland may well have a different outcome in the medium-to-long run.

The debate on the euro and related policies was replaced by procedures, threats, and orders that increasingly lack credibility. The lack of enthusiasm for a currency that a few years ago was seen as the crown jewel of European integration is increasingly evident. Countries that still a few years ago were longing to enter the euro, such as Central European countries, canceled this event from their agenda. In 2015, the first accession country, Iceland, unilaterally withdrew and canceled negotiations for EU membership. A Eurozone country, Greece, was close to exiting the euro in 2015, and a non-euro country, Great Britain, held a referendum which decided in favor of Brexit. Differences among member countries are growing, thereby making the common currency increasingly unsustainable and costly. The perspective of Brexit is apparently acting as a detonator that could lead to any outcome for the Eurozone: from its strengthening in a probably multispeed EU to the disruption of the Eurozone.

What are the causes of a potential economic, political, and social disaster? Why is the EU unable to find a solution, in spite of the bold and increasingly determined action of its Central Bank? Why is the European Commission so evidently powerless? And why are national governments, the real repositories of power in the EU together with the European Central Bank (ECB), so clearly unable to find a viable compromise, let alone a solution to mounting dangers? Why is the present situation so evidently dangerous for democracy and the constructive cooperation among European countries? Is this the beginning of the end or is it the end of an ineffective period from which a new Europe will emerge?

Theories of optimum currency areas (OCAs) are a good starting point for analyzing these problems and assessing the Eurozone perspectives. The chapter starts by considering why it is important that a monetary union is an OCA, in order to avoid the internal differences becoming structural factors that jeopardize the sustainability of the monetary union (Section 1). Section 2 reviews the benefits and the costs and disadvantages of an OCA. In Section 3, OCA criteria are considered and used to compare the Eurozone situation, with the United States taken as a benchmark. When a monetary union such as the Eurozone is not a perfect OCA, adjustment is more problematic and costly and requires policies and reforms. This is discussed in Section 4. However, as is considered in Section 5, the Eurozone is an incomplete and asymmetric monetary union, and this situation makes adjustment to asymmetric shocks problematic and leads to perverse consequences. As stressed in Section 6, the fundamental problem is the existence of incompatible and conflicting economic and fiscal philosophies within the Eurozone, in particular due to the dominance of the German ordoliberal approach in combination with austerity policies imposed by international organizations for years. Since this standard approach has failed to reestablish a viable situation, the Eurozone is in search of alternative policies, which Brexit makes dramatically urgent. Section 7 concludes in discussing some recent proposals.

Monetary Unions and OCAs

Any social undertaking including a monetary union has costs and benefits (Baldwin and Wyplosz 2012). A common currency area has one unique central bank and monetary policy, which cannot deal with the asymmetric effect of shocks in the different parts of the monetary union. Since asymmetric shocks cannot be avoided and the countries that form a monetary union have differences,2 there must exist both market and policy devices for the monetary union to be viable. Market devices work without requiring any explicit intervention by policymakers. However, they require proper institutional frameworks to be effective. OCA theories highlight the most important among them. One important device that was invoked for years as sufficient to guarantee the sustainability of the Eurozone is the so-called private insurance mechanism.3

National policy devices include fiscal policies (growth policies, internal devaluation4) and structural and institutional reforms that make the economic system more effective and efficient, with lower transaction costs. Various devices were discussed at European level, but hardly implemented. An important yet slowly implemented direct device is the creation of a European Banking Union, which includes a Single Supervisory Mechanism providing a framework for a more integrated banking market, and a Single Resolution Mechanism facilitating greater risk-sharing across borders. The Banking Union should also include, soon, a European Deposit Insurance Scheme, but this step is meeting serious resistance, particularly from Germany.

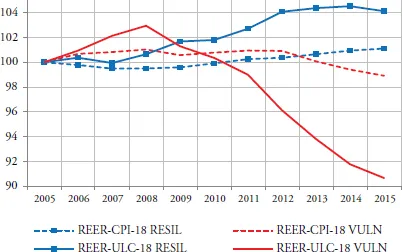

A country which is part of a monetary union cannot make use of depreciation of its nominal exchange rate to bring its cost level in line with its competitors. When incomes converge to the competitors’ level, but productivity and prices do not, a monetary union leads to the appreciation of the real exchange rate for the vulnerable economies. This was evident until the crisis (Figure 2.1). Such appreciation has to be adjusted by improving performance or decreasing costs and incomes in vulnerable countries through structural (internal devaluation)5 and institutional reforms6 or by increasing them in resilient countries. The latter step is likely to be opposed, since this would decrease the international competitiveness of resilient countries. However, this adaptation has negative long-run consequences for the vulnerable countries and may lead to tensions, and even the disruption of the union. In the Eurozone, the recovery of competitiveness of vulnerable countries was implemented entirely through the decrease of unit labor costs, due to internal devaluation policies (Figure 2.1).

There are different ways for reducing costs and improving performance in a monetary union through: (1) decreasing public expenditure and cutting taxes; (2) structural reforms that decrease costs (e.g., by cutting wages, pensions, and welfare); and (3) fostering investments (e.g., to make infrastructure better and more efficient). Each of these solutions presents trade-offs and disadvantages. Decreasing public expenditure is likely to decrease employment and weaken services and perhaps effectiveness in collecting tax revenues. Investments are a strategic and fundamental answer, but are costly in the present and give positive outcomes after some time, thus making their financing problematic in vulnerable countries.

Figure 2.1 Real Effective Exchange Rate.

Note: Deflator: Unit labor costs in the total economy and consumer price indices (18 Trading Partners), 2005 = 100. A rise in the index means a loss of competitiveness. Data in this figure and the following figures refer to unweighted averages.

Source: Author’s own figure based on data from Eurostat.

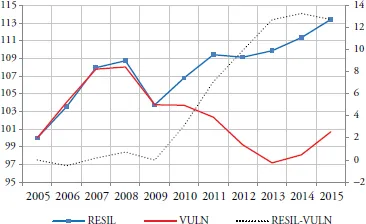

The decrease of wages and the weakening of the rights of workers (e.g., decreasing welfare or pension rights) meet social opposition and are likely to increase income disparities. These effects may easily weaken aggregate demand and incentives to work. The consequence may be smaller internal market and lower investment, with long-term negative consequences (Figure 2.2).

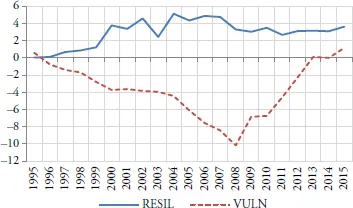

Moreover, the depressive effect of wage cuts is usually fast and permanent, while prices are sticky. This redistributes income to the disadvantage of labor and depresses consumption and consequently investment. However, austerity policies may help to adjust current accounts of vulnerable countries, mainly through import cuts. The most noticeable effect is that adjustment falls entirely upon vulnerable countries and further worsens their economic situation (Figure 2.3).7 In the long run, price and wage reduction and investment decrease can push vulnerable countries to a low-level equilibrium and low-skill specialization and slow technical progress.

Figure 2.2 Cumulative Gain or Loss of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in the Eurozone, 2005 = 100.

Note: Right scale for RESIL-VULN. The recovery for vulnerable countries in 2014 is entirely due to the strong growth of the Irish economy, which continued in 2015. In 2015, the economies of Spain and Cyprus had good performances.

Source: Author’s own analysis of Eurostat data.

A sounder solution is institutional reform, i.e., reforms that reestablish the conditions for an efficient and effective economic system that supports the economy’s competitiveness. Institutional reforms include fundamental solutions for decreasing transaction costs of economic activity, upgrading competition, linking wages to productivity and checking profits through competition, disrupting rents, and activating incentives. Examples are the reform of public administration, flexibility of markets, efficient welfare system, liberalization and effective regulation, entrepreneurship, and innovation.

Figure 2.3 Current Account Balance (in Percentage of GDP).

Source: Author’s own figure based on data from the Eurostat database.

Both structural and institutional reforms require time to be effective, involve serious costs, and may foster political and social opposition. A reasonable precondition for a well-working monetary un...