- 684 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

About this book

-->

Advanced Nonlinear Optics is a revised and updated version of Physics of Nonlinear Optics (1999). This book mainly presents the physical principles of a great number of nonlinear optical effects discovered after the advent of lasers. All these nonlinear optical effects can find their special applications in modern optics and photonics. The major categories of nonlinear optical effects specifically covered in this book are as follows: 1) Second-order (three-wave) frequency mixing; 2) Third-order (four-wave) frequency mixing; 3) Nonlinear refractive-index changes; 4) Self-focusing, self-phase modulation, and spectral self-broadening; 5) Stimulated scattering effects; 6) Optical phase-conjugation; 7) Optical coherent transient effects; 8) Nonlinear spectroscopic effects; 9) Optical bistability; 10) Multi-photon nonlinear optical effects; 11) Fast and slow light effects; 12) Detailed theory of nonlinear susceptibilities.

-->

Request Inspection Copy

--> Contents:

- Introduction to Nonlinear Optics

- Fundamental Knowledge of Nonlinear Polarization of a Medium

- Second-Order Nonlinear (Three-Wave) Frequency Mixing

- Third-Order Nonlinear (Four-Wave) Frequency Mixing

- Intense Light Induced Refractive-Index Changes

- Self-Focusing, Self-Phase Modulation, and Spectral Self-Broadening

- Stimulated Scattering of Intense Coherent Light

- Optical Phase Conjugation

- Optical Coherent Transient Effects

- Nonlinear Laser Spectroscopic Effects

- Optical Bistability

- Multi-Photon Nonlinear Optical Effects

- Principles of Fast and Slow Light Propagation

- Detailed Theory of Nonlinear Susceptibilities

- Appendices:

- Physical Constants Commonly Used in Nonlinear Optics

- Numerical Estimates and Conversion of Units

- Tensor-Elements of the Linear Susceptibility for Crystals and other Media

- Tensor-Elements of the Second-Order Susceptibility for Various Crystal Classes

- Tensor-Elements of the Susceptibility of Second-Harmonic Generation for Various Crystal Classes

- Tensor-Elements of the Third-Order Susceptibility for Crystals and other Media

- Tensor-Elements of the Nuclear Third-Order Susceptibility in Born-Oppenheimer Aproximation

- The Solution of Eq. (8.4–14)

- Derivation of Formulae for Self-Induced Transparency of a 2π-Pulse

- Index

-->

--> Readership: Graduate students and research scientists/engineers who work in optics, electro-optics, laser technology, opto-electronics, quantum electronics, photonics, engineering, chemistry and other multi-disciplinary fields. -->

Keywords:Optical Physics;Nonlinear Optics;PhotonicsReview:

Review of the First Edition:

"It is an excellent handbook that can be used by research scientists and engineers working in optics, laser technology, opto-electronics, photonics, chemistry, and a number of other multidisciplinary fields... The book is well referenced and has a good table of contents. I would recommend it as a must for any optics library."

Optics & Photonics News

Key Features:

- Covering a broad scope of modern nonlinear optics

- Presenting both schemes of semiclassical theory of nonlinear susceptibility and quantum theory of radiation

- Emphasizing equally the fundamental theories, key experimental results, and various special applications

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

CHAPTER 1

Introduction to Nonlinear Optics

1.1Definition of Nonlinear Optics

1.1.1Linear optics

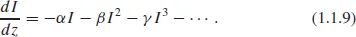

1.1.2Nonlinear optics

Table of contents

- Cover

- Halftitle

- Title

- Copyright

- Preface

- Contents

- 1. Introduction to Nonlinear Optics

- 2. Fundamental Knowledge of Nonlinear Polarization of a Medium

- 3. Second-Order Nonlinear (Three-Wave) Frequency Mixing

- 4. Third-Order Nonlinear (Four-Wave) Frequency Mixing

- 5. Intense Light-Induced Refractive-Index Changes

- 6. Self-Focusing, Self-Phase Modulation, and Spectral Self-Broadening

- 7. Stimulated Scattering of Intense Coherent Light

- 8. Optical Phase Conjugation

- 9. Optical Coherent Transient Effects

- 10. Nonlinear Laser Spectroscopic Effects

- 11. Optical Bistability

- 12. Multi-Photon Nonlinear Optical Effects

- 13. Principles of Fast and Slow Light Propagation

- 14. Detailed Theory of Nonlinear Susceptibilities

- Appendices

- Index

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app