![]()

Chapter One

Introducing Bacteria

In nature, there are animals and plants of all forms and colors. But do you know there is also a mysterious group of tiny individuals, too small to be seen with the naked eye? These are called microorganisms. Microorganisms are tiny creatures that are less than 0.1 mm in size. There are many types of microorganisms. What people hear, see, and get in contact with are virus, mold, yeast, and bacteria. In this chapter, you are introduced to one member of the microorganisms’ world — bacteria.

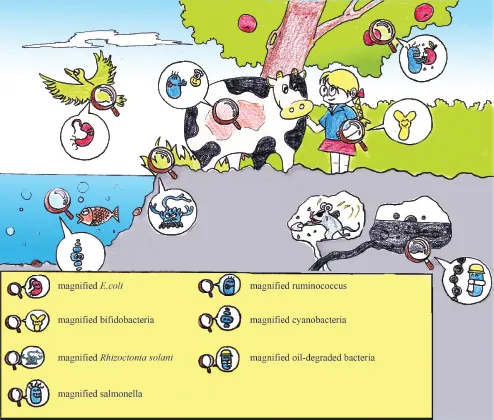

Bacteria are the earliest “residents” on Earth. Traces of them date back 3.5 billion years, whereas human beings have a history of only several millions of years. The tiny bacteria possess five characteristics that are impossible among higher organisms: (1) they have small volume but large surface area; (2) they absorb considerable nutrition and transform it quickly; (3) they are full of vitality, reproducing at high speed; (4) they constantly vary and are good at adapting; and (5) they have a great variety distributed in many places. They are everywhere. With proper methods, people can find these tiny fairies in almost all corners of the world. Figure 1-1 is a personification of bacteria sojourned in animals, plants, soil, water, and air, which can only be observed through microscopes. These bacteria include rumen bacteria in cows, Bifidobacterium in children’s stomachs, cyanobacteria in oceans, enterobacter in birds’ stomachs, sheath blight bacteria in ailed rice, and the oil-degraded microorganisms that consume petroleum.

Figure 1-1: Tiny fairies everywhere.

What do Bacteria Look Like?

Bacteria are single-celled organisms, namely one cell is one organism.

We could hardly see how bacteria look like with our eyes. But with the help of microscopes, we can see clearly their various shapes and forms. They most commonly appear in spherical, rodlike, or helical shapes and are, respectively, called coccus, bacillus, and spirochete.

Coccus

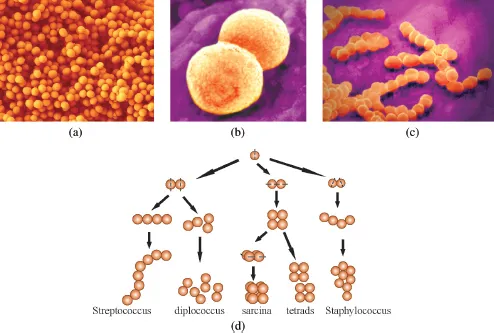

In case of bacterial cell division, when the new organism exists independently, it becomes single coccus, such as

Micrococcus luteus. When two cells are arranged in pairs, they are called diplococcus, for example

Pneumococcus. When multiple cells form a chain structure, they

are called streptococcus, for example

Streptococcus lactis. When divided twice, four cells link into “

” shape and become tetrads, for example

Micrococcus tetragenus. When the cell divides in three vertical directions into eight, the split cells pile together in the shape of a Rubik’s cube, which is called sarcina, for example

Sarcina lutea. When there are no specific directions of division, the new organisms appear in grapelike clusters called staphylococcus, for example

Staphylococcus aureus.

Figure 1-2(a) is a scanning electron microscope (SEM) photograph of

Staphylococcus aureus;

Fig. 1-2(b) and

(c) are computer-generated figures of

Pneumococcus and

Streptococcus lactis.

Figure 1-2(d) shows the division and arrangement of coccus.

Figure 1-2: Coccus and its reproduction and order. (a) Staphylococcus aureus (electron microscope; (b) Pneumococcus (computer simulated); (c) Streptococcus lactis (computer simulated); and (d) reproduction and order of coccus.

Bacillus

The shape of the two ends of bacilli varies. Some are round and blunt, some are flat, and some have a sharp tip. The length-to-diameter ratio among bacilli also varies. Some appear short and chubby, some appear tall and slim, and some have beard-like flagellum and pilum. Figure 1-3 is an SEM photograph of Escherichia coli.

Figure 1-3: Escherichia coli (left, scanning electron microscopy; right, transmission electron microscopy).

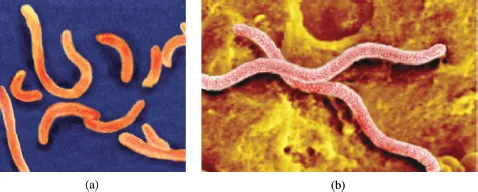

Figure 1-4: Helicobacter: (a) comma bacillus and (b) Helicobacter pylori.

Helicobacter

Helicobacter are the “dancing bacillus”, or bacterial cells with a curved shape. They are divided into two types according to the degree and hardness of their curves. The first type is vibrio with short cells and a single, archlike curve, for example Vibrio cholerae. The second type is helicobacter. The cell curves more than twice, like a spiral, and is usually hard, for example Helicobacter pylori. Figure 1-4 shows computer-generated helicobacter.

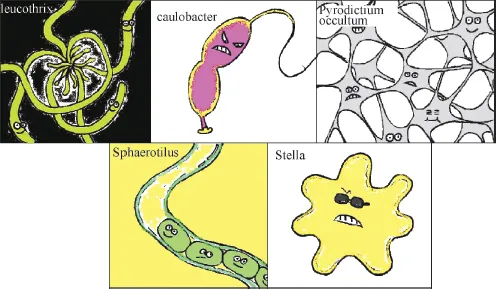

Figure 1-5: Bacteria with special shapes.

Apart from these, bacteria have many other shapes, for example, bacteria with appendage and handle, or bacteria shaped like thread, star, or rectangle. Figure 1-5 shows bacteria of special shapes.

In different phases and under different conditions, the shape of bacteria changes considerably. Generally, young bacteria or bacteria growing under suitable conditions appear in a certain neat and normal shape. Old bacteria or bacteria growing under unusual conditions will display irregular shapes. Compared to animals and plants, the changes in shape of bacteria are more difficult to comprehend.

How Big are Bacteria?

Bacteria are small and light. They are so small that you cannot see them with naked eyes; they are so light that you cannot weigh them.

Bacteria can only be seen when enlarged hundreds or thousands of times under a microscope. We can measure the size of a bacterium using micrometer under a microscope; or we can use projection or photograph, and measure the enlarged figure. The size of bacteria is measured in micrometers: 1000 micrometers is equivalent to 1 millimeter.

Take Escherichia coli for example. It has an average length of 2 µm and a width of 0.5 µm. 1500 Escherichia coli lying head to toe in a line is only as big as a sesame seed (3 mm); 120 Escherichia coli standing shoulder to shoulder is just as wide as one single hair (60 µm).

Biggest bacterium

The April 1999 issue of Science magazine reported the largest bacteria ever discovered in history. This coccus has a 0.1–0.3 mm diameter on average, and the largest can reach 0.75 mm. This is 100–300 times larger than normal coccus (Fig. 1-6). Normal bacteria, in comparison with this huge bacterium, appear like newborn mice in front of a blue whale. This bacterium was discovered by Schultz, a biologist at Max Planck Institute for Marine Microbiology in Germany, in the riverbed sediments in Namibian coast along Southwest Africa. This is the largest bacterium in the world discovered by far that is perceivable to the naked eye.

Figure 1-6: Namibia sulfur pearl bacteria. Arrow indicates the reason for the shine in bacteria — considerable sulfur in bacteria.

Generally, this bacterium lives in seabed sediments with high concentration of hydrogen sulfide. It has a bright white color due to sulfur particles. When arranged in a roll, they look like a shining pearl necklace. Therefore, Shulz and other researchers named this bacterium Thiomargarita namibiensis. The sediment where this bacterium lives lacks oxygen but is rich in nutrition. There is also considerable hydrogen sulfide. Although hydrogen sulfide is poisonous to animals, it is food for this bacterium, because the latter can oxidize sulfur with the nitrate in its cell. The discovery of this bacterium has provided more precise evidence of the coupling effect between sulfur cycle and carbon cycle. These two main cycles in the ocean have been considered irrelevant up until recently.

There are also amazing microorganisms living under extreme conditions. For example, there are ancient bacteria living in springs with a temperature of more than 100 °C; there are bacteria in the Antarctica seabed and glacier, where temperature is below zero. The discovery of these microorganisms is exciting not only to those studying the origins of life but also to biologists.

Smallest bacterium

In 1997, Finnish scientist Kajander and his colleagues, while culturing mammalian cells, discovered a bacterium that could pass through the 100-µm bacteria filter. This bacterium is normally 1/20 the size of normal bacteria. The smallest bacterium discovered by far, it is accordingly named nanobacterium. Comprehensive research has revealed that nanobacterium is an amazing tiny thing that is capable of self-duplication and mineralization. It is also related to many diseases. Scholars from NASA believe it causes kidney stones in astronauts, as it exists at the center of calcium phosphate in the stones. To study the features of nanobacterium, NASA placed the bacterium in bioreactors that simulate outer space environment. Under microgravity, nanobacterium duplicates five times faster than under normal gravity. Nanobacterium can be infected among astronauts living in constrained space. This amazing little thing is also found in other diseases such as Alzheimer, heart disease, prostatitis, and some cancers.

The Little Fairy Everywhere

Although not perceivable with the naked eye, bacteria leave their traces everywhere on Earth, from the flamboyant city to tranquil forest, from snow-covered mountains to vast seas, from the warm and rainy tropics to uninhabited deserts, from freezing polar zones to boiling volcanoes, from the surface of animals and plants to their insides, from dust floating in the sky to fossils lying thousands of years underground. Bacteria have made their home everywhere.

Humans seem to live in a sea of bacteria. When you are playing or studying, there are numerous bacteria at your company; even in your tidy dorms, there are countless bacteria sharing the space with you. The environment we live in and the things we touch are often contaminated by bacteria, such as cleaning cloth, garbage bags, curtains, door handles, cutting boards, coins, public telephones, books and newspapers, tables and chairs, switches of electronic devices, bedroom furniture, and even some food. Research shows that a dirty hand carries 400,000 bacteria; among a random selection of 700 RMB notes, Escherichia coli, indicator of intestinal bacterial infection, are detected on 440 notes.

Bacteria in human bodies

Do not assume that bacteria will not like you, if you are a clean person; and do not assume that the less bacteria on your body the better. Scientific research shows that once you leave your mother’s uterus, all types of bacteria attempt to “invade” each part of your body by various means, and they grow and regenerate, feeding on the nutrition in your body. Scientists speculate that on an adult body reside up to thousands of billions of bacteria, of more than 400 different types. The number of bacteria surpasses 90% of the total living cells of the human body (this includes all the living cells that make up the human body, as well as the microorganisms living inside the human body). Bacteria’s favorite camping places include mouth, nostrils, intestines, and the skin.

Mouth

How many bacteria are there in the mouth? There are no bacteria in the mouth of a newborn. But as the baby announces his or her arrival into the world with a cry, bacteria, along with air, enter his or her mouth and start inhabiting there. Later, when feeding on milk, either through breast or feeding bottle, more and more bacteria enter the baby’s mouth. Specialists estimate that in a clean mouth, 1000–100,000 bacteria reside on the surface of each tooth; in a not so clean mouth, there can be 100 million to 1 billion bacteria; 1 mg of plaque contains approximately hundreds of millions of bacteria.

Why there are so many bacteria in the mouth? It is because the mouth continuously secretes saliva. Saliva has 100% humidity and a temperature of 37 °C. Together with breathing, speaking, and eating meals, this is a greenhouse for bacteria, providing sufficient nutrition and oxygen for their growth and reproduction.

Like humans, bacteria have different races and groups, and they occupy their own living spaces in the mouth. Some live together at the cheeks; some gather at the ventral tongue; some prefer the back of the tongue; and anaerobic bacteria live in groups between the teeth.

Normally, despite staphylococci, streptococci, Escherichia coli, and other hundreds of types of bacteria residing in the mouth, the body can still be perfectly fine. Some bacteria are even beneficial by assisting food digestion. But when the body is exhausted and the immunity level is low, or when it is stimulated by other factors, bacteria will multiply in large numbers, creating a focus of chronic infection. The most common symptom is periodontitis. As the mouth is at the upstream of the respiratory and digestive tract, mouth infections can easily lead to sore throat, tonsillitis, tracheitis, pneumonia, ulcer, tuberculosis of the intestines, and many other diseases. Meanwhile, because of anatomic reasons, mouth infection can affect nostril and middle ear. Some researches show that Helicobacter pylori, which is responsible for gastritis and ulcer, can be detected not only in the pylorus but also in mouth, teeth, and saliva.

Nostril

Bacteria in the nostril are all trapped in nasal hair, which filter the air we breathe in. These bacteria are often the grapelike Staphylococcus aureus. Deep in the nostril, there are many chainlike streptococci. Meanwhile, under good health conditions, other bacteria detectable in the nostril include pseudodiphtheria. According to expert estimation, 500 bacteria are breathed out every minute, and 4000 each time when you sneeze.

Normal...