![]()

Part I

INTRODUCTION

![]()

Chapter 1

THE PARAMOUNT POSITION OF PRODUCTION

In his elegant and persuasive magnum opus, John Kenneth Galbraith (JKG) devoted a chapter with the above title. We repeat it here, with a summary of Galbraith’s chapter in The Affluent Society. This position of production is not simply a matter of belief, though that is important, but rather of reality. First, we spread caution to the winds about production, then we take a look at the national income accounts and the place of production there. We end on the quite unconventional note that income is more important than production, followed closely by employment. As promised, the first words of caution emanate from JKG. Why, we must ask, does production have such a prominent position in the USA and other economies?

Increases in production have long been celebrated. Higher production is a measure of achievement. When it comes to production as a test of performance, there is no difference between Republicans and Democrats, right and left, white and middle-class blacks, Catholics and Protestants. It is common ground for the Chair of Americans for Democratic Action, the President of the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, and the President of the National Association of Manufacturers. Even the head of the AFL–CIO can concede on this one, though full employment cannot be taken off the table.

A small voice regularly tells us that production is not everything. Perhaps it is the voice of an angel for we hear constant reminders that there is a spiritual side to life. Those who remind us of this will receive a respectful if not attentive hearing. Still, to be sensible and practical is to believe in the prestige that production accords us. To say that CEOs understand production is to pay them the highest of complements. For one to be useful, they must be productive. Anything that interferes with the supply of more and better things is resisted with religious-like enthusiasm. In fiction, Ayn Rand’s Hank Rearden is a vindication of the creativity of the industrialist, the author of material production.1

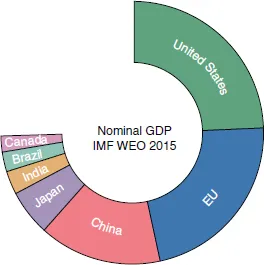

The importance of production transcends USA boundaries, but is not confined therein. In what Galbraith calls the conventional wisdom, the level of GNP is the most frequent justification of American civilization. It is often said in this regard that the American standard of living is “the marvel of the world.” While to a considerable extent, it is, we will nonetheless raise questions regarding the sanctity of GNP. Still, the perspective of the world is often the one given by a picture of relative GNP such as that of Figure 1.1, which shows the relative positions of seven economies in 2015. From the perspective of the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the Economic Union (EU) is like a United States of Europe. The rank order has the USA first, followed respectively by the European Union, China, Japan, India, Brazil, and Canada. The rank order for most of the “countries” of the world is provided in Appendix A for 2016 (IMF), 2016 (World Bank), and 2015 (United Nations). Ignoring the EU as a “country,” China and Japan are followed by Germany, the UK, France, India, Italy, and then Brazil.

In the supra-surplus economies, goods are comparatively abundant. The abundance of sun and rain, though they are no less important, are taken for granted. Still, worldwide there is much malnutrition, but more die in the supra-surplus countries from too much food and drink than of too little. As Galbraith suggests: “For many women and some men, clothing has ceased to be related to protection from exposure and has become, like plumage, almost exclusively erotic.”2 Those who doubt this do not go to the movies or nightclubs. And, yet, production remains central to our thoughts. It continues to measure the quality and progress of civilization. So large does production bulk in our thought that we can only suppose a vacuum must remain if it should be relegated to a smaller role. As we soon shall see, there are other things. But first we will examine more closely our present preoccupation with production.

Figure 1.1 A Pie Chart Displaying the World’s Seven Largest Economies by Nominal GDP — The United States, the European Union, China, Japan, India, Brazil, and Canada.

Ways to Expand Production

There is more than one way to expand production. In principle, according to Galbraith, there are five distinct ways worth listing formally.3

(1)The available productive resources, namely labor and capital (including raw materials), can be more fully employed. Even capital can be idle, though traditionally this condition has been applied to labor.

(2)Given available production techniques, these resources can be more efficiently utilized. There are different ways of combining capital with labor, but there should be one especially advantageous way.

(3)The labor force can be increased, through new entrants, immigration, or population increases.

(4)The supply of capital, which in some theories can serve as a substitute for labor, can be increased. We should stress that in the economist’s long run, capital and labor are more likely to be substitutable. We will return to this issue.

(5)Technological innovation can occur. As a consequence, more output can be obtained from the given supply of labor and capital. Moreover, the new capital will likely be enhanced by the new technology.

It is difficult to know which is more important or effective. Perhaps an equal emphasis should be placed on each. That having been said, economists generally have focused on the top two because they best fit the orthodox paradigm. Changes are closely interrelated and studies of the comparative effect of these five measures do not produce unambiguous results. An early study, still cited as important, was for the period between 1859–1873 and 1944–1953. It shows that net national output increased at an average annual rate of 3.5 percent, of which about half (1.7 percent) can be attributed to the increase in capital and labor supply. The remainder probably was due to technological improvement in capital and parallel improvement in the people who devise the better capital equipment and operate it. In more recent times, a growing share of the increase in output is attributable to such technological advances and a declining share to mere increases in the quantities of capital and labor.4

No one questions the importance of technological advance for increasing production (and also generating new products) from available resources. Little, however, is done to improve the volume of this investment, except when mandated by some military emergency. We tend to accept whatever investment in technology is being made and applaud the outcome.

Economic growth depends on the growth rates of productivity and the labor force. Paul M. Romer (born November 7, 1955), currently Chief Economist and Senior Vice President of the World Bank, is responsible for intensive research on productivity and its causes. Yet, he is of several minds regarding the relationship of inputs and technology to final output. For example, he has taken the contrary positions that economic growth is endogenous and exogenous. The role of technology is often the source of these two positions. Technology is endogenous when it is embodied in existing capital and exogenous when it is viewed as a residual (after capital and labor quantities are accounted for). In one paper he concludes that an increase in the size of the market or in the trading area in which a country operates increases the incentives for research and thereby increases the share of investment and the rate of growth of output, with no fall in the rate of return on capital.5 A higher level of income seems to be associated with a higher rate of savings and investment. Interestingly, higher exogenous savings have little relationship with higher technological change and productivity growth. This finding does considerable damage to the long-held belief that thriftiness is next to Godliness.

In another paper, Romer focuses on economic growth as endogenous.6 As he notes, endogenous growth distinguishes itself from neoclassical growth theory by emphasizing that economic growth is an endogenous outcome of an economic system, not the result of forces that impinge from outside. In this paper he rejects some of his earlier research findings. In particular, he rejects the idea that the quantity of physical capital is an important determinant of productivity. His earlier emphasis on production functions using capital and labor inputs was mistaken. Instead, he now likes an early paper (1987) he did on research and knowledge as being in the right direction. He refers to five facts that can be used to explain economic growth. (1) There are many firms in a market economy. While monopolies exist, output is not concentrated in a single, economy-wide monopolist. (2) Discoveries differ from other inputs in the sense that many people can use them at the same time. Such discoveries include the idea behind the transistor, the principles behind internal combustion, the organizational structure of a modern corporation, and the concepts of double entry bookkeeping. These all have the property that it is technologically possible for everybody and every firm to make use of them at the same time. (3) It is possible to replicate physical activities.

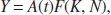

The aggregate production function can be estimated. If the function is represented in the form Y = AF(K, H, L), then doubling all three of K, H, and L should allow a doubling of output (Y). A represents technology and is non-rival (see Fact 2) because the existing pieces of information can be used in all instances of productive activity at the same time. H represents human capital and L is physical labor. Note that land is not an input, which would be very embarrassing for the output of farming and fisheries. (4) Technological advance comes from things that people do. Discovery will seem to be an exogenous event in the sense that forces outside our control seem to determine whether it succeeds. The aggregate rate of discovery is endogenous. When more people start prospecting for gold or experimenting with bacteria, more valuable discoveries will be found. (5) Many individuals and firms have market power and earn monopoly rents on discoveries. Though information from discoveries is non-rival (Fact 2), economically important discoveries usually do not meet the other criterion for a public good; they typically are partially excludable, or excludable for at least some period of time. Because people and firms have some control over the information produced by most discoveries, it cannot be treated as a pure public good. If a firm can control access to a discovery, it can charge a price that is higher than zero. It thus earns monopoly profits because information has no opportunity costs.

We must not forget the orthodoxy, which remains firmly neoclassical. A combo of American economists in the mid-1950s wrote a new, neoclassical orchestration with themes that are still played today. The new virtuoso was Robert Solow.7 Solow in the front row and Paul Samuelson in the second forsook any chorus about production taking place at fixed proportions of capital and labor. In a return to neoclassical growth rendition, the interest rate and wage rates are flexible and capital and labor easily substitutable, one for the other, depending on whether a low interest rate favors capital investment or a low wage rate favors bringing labor off the bench. These substitutions are sufficiently fine that the economy never really diverges from its stable path. Thus, the knife-edge threat to capitalistic stability is dulled by a new arrangement.

The nerves of the capitalist were soothed. The economy could be compared to a long-distance jogger who never changes pace and yet runs forever. Neoclassical growth theory still dominated Macro-dynamics in the late 1970s and remains textbook bound to this day. The theory, like the economy, had the endurance of the long-distance runner.

Robert Solow’s Nobel Prize in Economics came in 1987 and it was for his contributions to the theory of economic growth. His was a popular choice, for Solow is one of the most likeable persons on the planet. His main contribution to growth theory was to introduce the theme of technological flexibility. There was a variety of compositions for total production prior to factories and equipment being put into place. Thereafter, such production techniques became fixed, as indeed they are. The degree of intensity with which capital is utilized in production can vary over time and is a source of great flexibility for capitalist (or socialist) economies. It turns out that the permanent growth of output per unit of labor input (productivity) is independent of the saving and the investment rate. Rather, productivity growth depends solely on technological progress in a broad sense. Technological progress, little studied by economists, is the key that unlocks productivity growth.

The Solow Economic Growth Model

Solow served on the staff of the President’s Council of Economic Advisers and the neoclassical growth model provided a framework within which macroeconomic policies could be used to sustain full employment. Solow’s ideas were written into the 1962 Economic Report of the President for John F. Kennedy. Admittedly, however, steady growth depended upon tranquil conditions, the conditions prevailing during the late 1950s and early 1960s. As Solow has written, “the hard part of disequilibrium growth is that we do not have — and it may be impossible to have a really good theory of asset valuation under turbulent conditions.”8 He made that observation near the end of 1987, shortly after the stock market crash of October. We will address turbulent conditions later.

The basic Solow growth model can be simply expressed. During 1870–1999, national output in the USA increased at an annual rate of 3.5 percent. At the same time, per capita output increased at an annual rate of 1.8 percent. What factors, it is fair to ask contributed to these growth rates — population growth, capital expansion, improvements in education, natural resources growth? The simplest way to begin to answer this question is to write an aggregate production function for the economy that relates the level of output to the level of basic factor inputs, so

where A(t) represents technological change which is presumed to depend only on time, K is the capital stock, and N is the size of the labor force. Since A(t) is multiplicative, more output will be produced for the same amount of factor inputs (K and N). This means that technological change does not...