![]()

Part 1

Technology Management Models

![]()

CHAPTER 1

Technology Management Tools: Generalization, Integration, and Configurationa

Robert Phaal,*,† Clare Farrukh†,‡ & David Probert †,§

Abstract

Managers in technology-intensive businesses need to make decisions in complex and dynamic environments. Many tools, frameworks, and processes have been developed to support managers in these situations, leading to a proliferation of such approaches, with little consistency in terminology or theoretical foundation, and a lack of understanding of how such tools can be linked together to tackle management challenges in an integrated way. As a step towards addressing these issues, this chapter proposes the concept of an integrated “toolkit”, incorporating generalized forms of three core technology management tools that support strategic planning (roadmapping, portfolio analysis, and linked analysis grids).

Keywords: Tools; frameworks; roadmapping; portfolio.

1.Introduction

Managers and consultants use a wide range of tools and techniques to support strategic decision-making and action in increasingly complex, competitive and dynamic business environments. The impact of new technologies and short-ened innovation cycles place a greater demand on managers to make effective and timely decisions, supported by good quality market, competitive and technology intelligence. Such decisions typically require input from multiple functions and disciplines, and benefit from processes that support consensus. Management tools and approaches are needed to support such decisions.

The choice of what management tool to use, and how to deploy it most appropriately, can be very confusing, due to the proliferation of approaches developed by academics, consultants, and firms. For example, Phaal et al. (2005a) have identified more than 850 tools of the simple “2 × 2 matrix” kind, covering all branches of management, of which approximately 40 are used to support R&D project and option portfolio management. Examination of these portfolio tools indicates that many, while expressed in a range of different ways, are similar in type. Also, Phaal et al. (2001c) have explored the many formats that the technology roadmapping approach can take, and the various purposes to which it has been applied. The importance of focusing on management tool development is highlighted by the following statement by Rigby (2001): “The implementation of new management tools is often an expensive proposition costing companies millions of dollars in training and development, consulting fees, and other related costs”.

This paper seeks to address the issue of how technology management tools can be designed, developed, and deployed in a more rigorous fashion, to avoid unnecessary proliferation and to ensure that tools can integrate with each other and with business processes and systems. For example, it has been demonstrated that the roadmapping approach can be generalized to a form that can be customized to suit a wide range of applications (Phaal et al., 2004c; Lee and Park, 2005). The principles that enable roadmapping to be used in this way are considered in Section 3, based on experience gained over a period of eight years developing a practical approach for initiating technology roadmapping in firms and networks, involving more than 75 collaborative engagements with companies and other organizations (e.g. Phaal et al. (2001a; 2004b; 2005b)).

In addition, the way in which roadmaps can be deployed in conjunction with other technology management tools is considered, with particular reference to portfolio management methods (e.g. Cooper et al., 1998) and “linked analysis grids” (e.g. Lindsay, 2000). These concepts are extended further in Section 4 to propose a set of principles that could form the basis of a “theory” of technology management tool design and application, leading to the vision of a “universal toolkit” that can be configured to support a wide range of technology management decisions and processes. But firstly, the nature of management representations and approaches is considered in Section 2, to define terms and to understand the process through which management frameworks and tools can be developed in a robust manner.

2.Management Representations and Approaches

Brady et al. (1997) define a management tool as “a document, framework, procedure, system, or method that enables a company to achieve or clarify an objective”. Rigby (2001) states that “The term ‘management tool’ can mean many things, but often involves a set of concepts, processes, exercises, and analytic frameworks.” In his survey of management tools and techniques, Rigby focuses on broad areas such as strategic planning, benchmarking, pay-for-performance, outsourcing, customer segmentation, re-engineering, balanced scorecard and total quality management. This paper adopts a more specific and focused definition of management tool, described below.

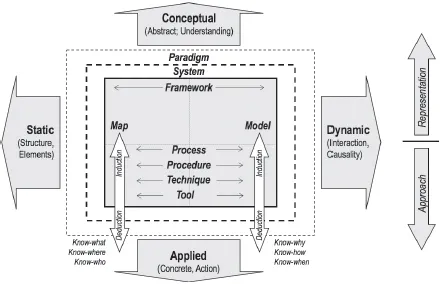

2.1.Meta-framework

The broad definitions provided by Brady et al. and Rigby do not distinguish between a number of related terms that are used in various ways by different management authors and practitioners, with little rigor or consistency. In order to clarify this situation, the “meta-framework” in Fig. 1 has been proposed by Shehabuddeen et al. (2000). This meta-framework structures a number of related terms for management representations and approaches (which collectively might be termed “methods”) according to two key dimensions: applied-conceptual and static-dynamic, defined as follows:

•Conceptual: concerned with the abstraction or understanding of a situation (cognitive models).

•Applied: concerned with concrete action in a practical environment (real world).

Figure 1. Meta-framework: management representations and approaches (Shehabuddeen et al., 2000; Phaal et al., 2004a); note, the boundaries between the various forms of representations and approaches are not distinct, and hybrid forms are indeed common.

•Static: concerned with the structure and position of elements within a system.

•Dynamic: concerned with causality and interaction between the elements of a system.

The relationships between the various terms that refer to management representations and approaches are implied by the structure shown in the Fig. 1, adopting the following definitions (although it is recognized that many management representations and approaches combine elements of more than one of these):

•A paradigm describes the established assumptions and conventions that underpin a particular perspective on a management issue (e.g. the authors of this chapter adopt an engineering problem-oriented paradigm).

•A system defines a set of bounded inter-related elements and represents it within the context of a paradigm.

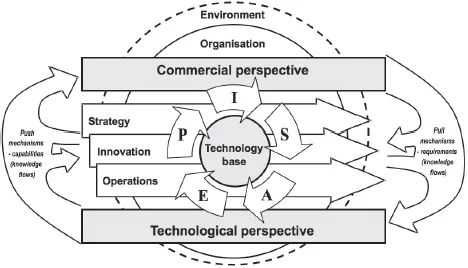

•A framework supports understanding and communication of structure and relationship within a system for a defined purpose (see example in Fig. 2).

•A map supports understanding of the static relationship between elements of a system.

•A model supports understanding of the dynamic interaction between the elements of a system (cause and effect; inforation flows).

•A process is an approach for achieving a managerial objective, through the transformation of inputs into outputs.

•A procedure is a series of steps for operationalizing a process.

•A technique is a structured way of completing part of a procedure.

•A tool facilitates the practical application of a technique.

2.2.Management Tools and Frameworks

The definition of management tool in the meta-framework is more specific than that provided by Brady et al. and Rigby, although the “nested” and interrelated nature of the concepts defined here implies that tools need to be considered in the context of the technique, procedure, and process within which they are applied, together with the conceptual basis on which they are founded (models, maps, and frameworks, together with the system and paradigm).

Figure 2. Technology management framework (Phaal et al., 2004a), highlighting how five technology management processes (Identification, Selection, Acquisition, Exploitation, and Protection) operate on the technology base of the firm (Gregory, 1995), typically embedded within the core business processes of the firm (strategy, innovation and operations).

Brown (1997) and Farrukh et al. (1999) list some principles of good practice for tool design. Tools should be: founding on an objective best-practice model; simple in concept and use; flexible, allowing “best-fit” to the current situation and needs of the company; not mechanistic or prescriptive; capable of integrating with other tools, processes and systems; result in quantifiable improvement; and support communication and buy-in. A manager faces a number of challenges when making use of such tools: How to find appropriate tools? How to assess the quality and utility of available tools? How to apply the tools in a practical setting or process? How to integrate tools with other tools, and with business processes and systems? (Phaal et al., 2005a).

This chapter focuses mainly on the issue of how technology management tools can be designed in such a way that they can be flexible (i.e. adapted to suit particular business situations) and integrated (with other tools, in the context of business processes). But firstly, the process of tool development will be addressed briefly, with reference to the meta-framework shown in Fig. 1, emphasizing the need to develop robust management tools that are based on well-founded conceptual frameworks linked to management theory.

The relationship between “representations”, which tend to be conceptual in nature, and “approaches”, which tend to focus on action, is important. The key point is that conceptual frameworks exist largely in the mind (although they may be articulated in the form of text and drawings), and requir...