![]()

INTRODUCTION

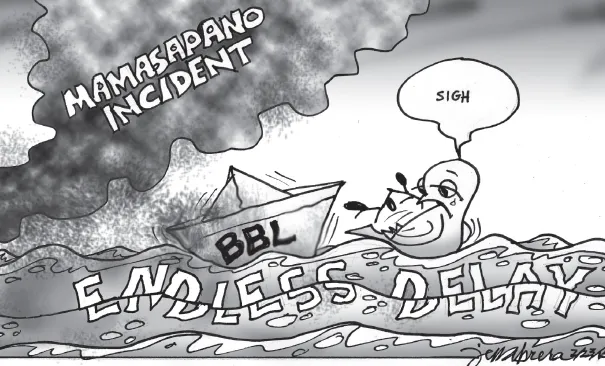

Less than a month after the botched counterterrorism operation of January 25, 2015, resulting in the Mamasapano Incident, it was already clear that prospects for peace were imperilled. This cartoon editorializes on the fate of the Bangsamoro Basic Law (BBL), a central element of the peace process.

Editorial cartoon by Jess Abrera © 2015 Philippine Daily Inquirer

![]()

THE TRAVAILS OF PROMOTING PEACE AND PROSPERITY IN MINDANAO

PAUL D. HUTCHCROFT1

This book project first got under way in October 2012, at a time of great promise for a negotiated end to the long-standing conflict between the national government and Muslim liberation forces in the southern Philippines. It was concluded in the first half of 2016, at a time of great frustration over the current prospects of achieving an enduring peace settlement.

When we gathered for the Philippines Update in Canberra on 12 October, 2012, the Framework Agreement on the Bangsamoro had just been announced a few days earlier (on October 7) and the formal signing took place a few days later at the Malacañan presidential palace in Manila (on October 15). This took place in a spirit of great celebration, looking toward the creation of a Bangsamoro political entity that would bring a greater degree of autonomy to the Muslim-majority regions of Mindanao and the Sulu Archipelago in exchange for the formal decommissioning of the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF) as an armed force. Throughout the previous year, there had been growing hope that peace might finally come to the southern Philippines after more than 40 years of a conflict that has killed more than 120,000 persons and displaced millions.2 The turning point was a historic meeting between President Benigno S. Aquino III and Murad Ebrahim, the chair of the MILF, held in Tokyo in August 2011.

Over the subsequent fourteen months, in an often contentious process, peace negotiators diligently hammered out the framework for peace in repeated meetings in Kuala Lumpur. The momentum continued throughout 2013, and into the beginning of 2014, as the various elements were crafted through negotiations involving the panels of the Government of the Philippines (GPH) and the MILF: annexes on Transitional Arrangements and Modalities, Revenue Generation and Wealth Sharing, Power Sharing, and Normalization, plus an Addendum on Bangsamoro Waters and the Zones of Joint Cooperation. This led into the March 2014 signing of the Comprehensive Agreement on the Bangsamoro (CAB), once again in a grand ceremony at the presidential palace.

The next critical step was to obtain passage of implementing legislation. A Bangsamoro Basic Law (BBL) was drafted in painstaking and often contentious negotiations between palace lawyers and key leaders of the MILF, and submitted to Congress for its consideration in September 2014. Then came the January 25, 2015, Mamasapano Incident, a botched counterterrorism operation that led to the deaths of at least 64 persons, including 44 special force policemen, 17 MILF fighters, and 3 civilians. The other casualty was the progress of the peace process. After four decades of conflict—claiming the lives of tens of thousands of Muslim and Christian Filipinos, many in brutal circumstances—the overwhelming focus of much of the public came to be on the deaths of the 44 police officers (some in close-range combat, the gory details of which were captured on video and posted on YouTube). Mamasapano captured the headlines, and there was a marked decline in public support for the peace process. House and Senate committees each wrote their own new versions of the BBL, with many provisions veering away from the original bill to such an extent that they were deemed unacceptable by the MILF. By early 2016, there were few who held out any strong hope that the peace process would be concluded with success before President Aquino ends his term and a new president is inaugurated in the middle of 2016.

The 2012 conference was the first update to be held on the Philippines at the Australian National University (ANU) since 2005. It brought together leading experts to assess the latest political and economic developments in the Philippines, and was patterned loosely after Indonesia Update conferences that have been held annually at the ANU for the past three decades. The lack of regularity to Philippines Updates can be attributed most of all to the lack of Philippine expertise at the ANU (and even more so at other universities across Australia): there are a mere handful of scholars with dedicated interests in the Philippines, as compared to the dozens of scholars with dedicated interests in Indonesia. With the encouragement of the Embassy of the Republic of the Philippines in Canberra,3 and the support of the then Australian Agency for International Development (AusAID)4—now the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade—a small group of us5 decided to rejuvenate the ANU’s on-again, off-again tradition of hosting Philippines Updates (dating first to 1983, and continuing on with additional updates in 1986, 1990, 1992, 2000, and 2005).

As with the broader pattern of country updates at the ANU, our 2012 conference began with attention to national-level political and economic developments and proceeded to focus on a particular topic of interest to scholars, policymakers, and development practitioners. From the start, there was a very strong consensus within our planning committee that our focus should be on Mindanao. It was a “no-brainer” from three standpoints. First, we knew that the peace process was advancing in promising new directions and were convinced of the value of bringing together a range of international experts to examine a topic of such obvious current relevance (hence the title of the update, Peace Prospects and Development Challenges in Mindanao). Second, from a more practical standpoint, we wanted a topic that would elicit as much interest as possible across the Canberra policy community, from foreign affairs to aid and development cooperation to security and national assessments. Third, it was an opportunity to highlight the strong AusAID focus on Mindanao, including the large number of AusAID-supported scholars from Mindanao.

While there is indeed a very healthy and flourishing bilateral relationship between Australia and the Philippines, the relationship is relatively undervalued both in Canberra and Manila. Two key purposes of the Philippines Update, fully supported both by the Philippine Embassy in Canberra and by the former AusAID, were to (1) give more attention to the strong bilateral ties binding Australia and the Philippines and (2) build the foundations of an even stronger relationship between the two countries. The Philippines Update was viewed as an opportunity to showcase expanding bilateral connections—one important component of which is the Australian commitment to the Philippines in the realm of development cooperation—and to promote, more specifically, a broader network of academic, research, and policy linkages.

The timing of the 2012 Philippines Update was, on one hand, extremely fortuitous. We were combining key players from the negotiating table with a range of other scholars able to provide additional analysis—historical, political, and economic—on the long-standing quest for peace and prosperity in Mindanao. The conference, as noted above, coincided almost exactly with the signing of the Framework Agreement on the Bangsamoro (FAB). From the standpoint of pulling together an edited volume, on the other hand, our timing could not have been worse. As editor, I was never able (try as I might) to convince those who were deeply involved in the peace negotiations to suspend the process of peacemaking in order to write about the process of peacemaking. For those on the front lines (and that includes many of the contributors to this volume), the efforts to forge a lasting peace have been a non-stop effort—from the FAB of late 2012 to the annexes of 2013–14 to the CAB of early 2014 to the crafting of the BBL in the latter part of 2014 to the huge contention surrounding that law in the wake of the Mamasapano Incident in January 2015. Quite clearly, the analysis for this volume has come in the midst of many extremely important competing demands.

The volume now emerging from the 2012 conference is not therefore to be commended for meeting its original publication schedule. And nor, given the circumstances, is it the book we originally anticipated. This volume was originally conceived to be a “conference volume” examining what seemed to be the soon-to-be successful culmination of a peace process that can be traced all the way back to 1976. Over time, it has instead evolved into an in-depth examination of the latest stage of a still-ongoing peace process—focusing most of all on the years between 2011 and 2016—complemented by richly textured analysis of the historical, political, and economic context underlying one of the most enduring conflicts in the world. As the peace process resumes under President Rodrigo Roa Duterte (elected on May 9, 2016, and set to be inaugurated for his single six-year term on June 30, 2016), the analysis in this volume will be an extremely important foundational resource for understanding what didn’t quite bring success in this, the most recent phase of the protracted pursuit of peace and prosperity in Mindanao. There are widespread expectations that Duterte, the country’s first-ever president from Mindanao, will adopt a new approach in seeking to resolve the multiple conflicts that have long plagued his home island.

UNDERSTANDING THE NATIONAL CONTEXT

The central focus of this chapter is a survey of the analysis found in the volume. Following the tradition of country updates at the ANU, this volume begins with attention to the national context before proceeding to in-depth examination of a more specific concern.6 Ronald Holmes, one of the leading political analysts in the Philippines, provides a comprehensive overview of the first five years of the administration of President Benigno Aquino. The analysis is framed around one very basic question: “Can the gains be sustained?”

Since his resounding victory in the 2010 election, running under the slogan kung walang corrupt, walang mahirap (if no one is corrupt, no one will be poor), Aquino has generally enjoyed exceptionally high approval ratings as he has embarked on various programs of combating corruption and curbing poverty. Holmes assesses the success of these broad programs. Anti-corruption activities began at the outset of the administration, with early successes in taking on “the big fish” of the previous administration. These were combined with other measures seeking to combat corruption, all part of the administration’s proclaimed intention to follow a tuwid na daan or “straight path”: promoting budget and procurement reform, nurturing more effective local governance (including in the Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao, or ARMM), addressing abuses in government corporations, and working to clean up revenuegenerating agencies. Anti-poverty measures included very substantial expansion of the conditional cash transfer program; a major revamping of the educational curriculum, supported by much higher budget allocations; a new excise tax on cigarettes and alcohol consumption, most of the proceeds of which are targeted to health programs; and the passage of the Reproductive Health (RH) Bill. Despite all of these measures, Holmes concludes, the war on poverty is far from a success: there have been only marginal declines in poverty incidence while measures such as the RH Bill suffer from incomplete implementation of the law.

In addition, Holmes examines administration initiatives seeking to regain the confidence of the business community (where measures of business competitiveness, as well as sovereign credit ratings, have registered marked improvement) and resolve the country’s two long-standing insurgencies (with the major new developments in talks with the MILF, as analyzed in this volume, standing in stark contrast to the moribund peace negotiations with the communist left).

Holmes’ chapter proceeds to examine the inner dynamics of the Aquino administration, which he characterizes as “stability despite division,” followed by analysis as to how executive-legislative ties have evolved amid the turbulence of a major pork-barrel scandal that broke forth in 2013. Although the alleged abuses took place prior to 2010, Holmes asserts, the response of the Aquino administration nonetheless “put into question the administration’s resolve to follow the ‘straight path’.” Creative solutions helped to maintain cordial ties between the executive and the legislature, but several issues have strained relations between the executive and the judiciary—most of all a July 2014 Supreme Court ruling against the constitutionality of a major administration budget initiative (the Disbursement Acceleration Program).

The final chunk of the Holmes analysis focuses on missed opportunities for reform. In a section aptly entitled “Where’s the party?,” Holmes criticizes the failure of the president to build up the Liberal Party with which he (and his family) have long been associated. One telling example is how only a small number of party mates were included in a multiparty senatorial slate named by (and named after) the president in 2013. In addition, Holmes notes, this has been accompanied by a failure to support party development measures and more generally by a lack of attention to national-level political reform. “Despite his reform pronouncements,” Holmes writes, “the president has failed to effect strategic reforms in the basic character of Philippine political institutions” and thus, “lamentably … put in peril the sustenance of his claimed legacy, a government that treks the straight path.” Returning to the central question that motivated his analysis, Holmes concludes that the “valuable gains” of the Aquino administration may in the end prove not to be sustainable.

HISTORICAL FOUNDATIONS, CONTEMPORARY IMPLICATIONS

In analyzing the present juncture of the effort to bring peace and prosperity in the southern Philippines, it is essential to begin with an examination of the historical foundations. This is provided by Patricio N. Abinales, a political scientist whose past work has traced the process, in the American colonial era, whereby Muslim Mindanao came to be conceived of as part of the Philippine nation-state. Abinales’s overarching goal is to debunk a number of prevailing “orthodoxies” that have long obfuscated analysis of the conflict in Mindanao as they have come to be “shared by the most disparate of social and political forces.” This problematic analysis, Abinales further asserts, has contributed to the repeated failures to achieve peace in the southern Philippines.

In his chapter, Abinales focuses attention on five closely interrelated elements of the “orthodoxy.” One core element of the dominant narrative, he explains, is to exaggerate Christian-Muslim and majority-minority tensions (i.e., between a Christian population that rapidly became the majority population in Mindanao in the postwar years and a Muslim population that was rapidly minoritized). In fact, Abinales explains, Christian migrants generally avoided settling in areas that were already populated by Muslims. A second element of orthodox thinking is how it incorrectly “assumes a history of unceasing conflict” when conflict has actually “been the exception rather than the rule.” The very data used by advocates of this part of the orthodoxy show that no unified Moro anti-colonial resistance ever came to be. Whatever major battles waged between colonizers and Muslim groups, especially during the American period, were confrontations arising from local issues (tax collection, anti-slavery, etc.) with support that hardly went beyond a datu’s or a sultan’s sphere of influence. Moreover, far from being centuries old, the current conflict can be traced back to two specific junctures in the mid-1960s and early 1970s, namely “the filling up of the frontier and the determination of [President Ferdinand] Marcos to assert greater central state authority in Mindanao.” Third, the conventional narrative overstates the importance of “religion as an inspirational force for armed change.” The historical record, on the contrary, reveals multiple sources of conflict. Fourth, there has often been the mistaken assumption of “the omnipresence of a capable state” in Mindanao. In reality, Abinales argues, the corrupt and inefficient early postwar Philippine state failed persistently across many areas of activity, whether “supervising and regulating land acquisition,” providing adequate infrastructure, or ensuring basic education for Muslim children.

Fifth and finally, the Abinales chapter repeatedly underscores the failure of the prevailing orthodoxy to appreciate the enduring power of local Muslim elites as they have repeatedly shown their capacity “to outwit the state and outlast the separatists.” Abinales emphasizes both the elites’ long experience of collaboration with Manila (whether in the Spanish era, the American era, or the postcolonial era) as well as their strong base of power in local landholdings. The regional political economy, he concludes, “is more complicated than what the orthodoxy wants us to believe”; the postconflict goal of promoting equitable patterns of development (as articulated both by the current administration and the MILF) will need to confront the reality of local landed power if it is to be realized. Abinales uses the example of the Ampatuan clan to show how access to public office can be an effective means of acquiring more wealth. Prior to the horrific November 2009 Maguindanao massacre (of 58 political rivals and journalists), for which the family is facing charges, the Ampatuans had amassed not only a large armory but also great wealth (with ostensibly “public funds … held in privately owned accounts”). Local elites serve both as “the ‘official’ representatives of the community as well as the wielders of patronage and privatized coercion.” The stark reality, Abinales emphasizes, is that “local power … has been decisive in shaping … political outcomes.”

Further historical foundations are provided in the chapter of Steven Rood, “The Role of International Actors in the Search for Peace in Mindanao,” which provides an analysis of the two processes of peace talks that can be traced back to the 1970s. Negotiations between the GPH and the Moro National Liberation Front (MNLF) yielded major accords in 1976, 1987, and 1996; these three agreements constitute an important backdrop to the GPH–MILF talks that began in 1997 and are a major focus of this volume.

Rood’s chapter traces the “organic” nature of international involvement in the Mindanao peace process, as it has evolved into “an elaborate architecture” that has in recent years involved nine countries (Asian, Middle Eastern, and European), two international organizations (the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation, or OIC, and the European Union) and seven international nongovernmental organizations. This architecture is distinctively hybrid, as viewed across two dimensions: state actors work alongside non-state actors and international actors work alongside domestic actors. No country in Asia has been more welcoming of international involvement, Rood argues, and the historical record demonstrates that “such involvement has encouraged progress in the protracted process of peacemaking” as it both brought “new perspectives to the Muslim organizations in Mindanao” and “helped to broaden the focus of the government in Manila.”

Three examples, from across the decades, help to illustrate the influence of international actors. First, the OIC’s willingness to recognize the “national sovereignty and territorial integrity” of the Philippines in the mid-1970s forced the MNLF to set aside the goal of independence in the run-up...