![]()

Chapter 1

Introduction: Politics and Governance in Indian States

The Problem

The resilience of the Indian state and the enduring character of India’s democratic governance make the political structure and process of the country exceptional among transitional societies. However, within the overall framework of India’s political stability and democratic governance, the state of orderly rule in India’s regions and localities presents a contrasting picture. Violent mobs on the streets of Srinagar in Kashmir, insurgency and armed secessionist movements in India’s North East, Naxalite violence in several federal States of India, and violent inter-community riots present a stark contrast to the norms of orderly rule in the rest of the country. This is puzzling. Why does the same constitution and institutional fabric not generate the same level of governance all over the country? And how does this state of low governance affect the stability of the country as a whole? How does India cope with these challenges to governance? And, from the point of view of management of the economy, growth, and domestic and foreign direct investment, do the regions that have experienced challenges to governance remain ‘open’ for business?

Issues of governance and democracy in transitional societies have generated a vast literature (Huntington, 1968; Kohli, 1990; Lijphart, 1996; Mitra, 2005). This book is aimed at engaging with this existing body of knowledge in terms of insights gained from an intra-system analysis of the Indian state, with a focus on three ‘difficult’ regions that have experienced severe challenges to governance in the past. Focused on a comparative analysis of regional governance, it asks: which policies and administrative and legal structures at the regional level promote governance? Further, how have India’s new social elites — many of whom have originated from the lower social orders — transformed themselves from rebels into stakeholders, and thus, into agents of law and order? What general and cross-national inferences can be drawn from the Indian case? By drawing on the logic of human ingenuity, driven mostly by selfinterest, the innovation of appropriate rules and procedures, and most of all, agency, of elites and their non-elite followers, the book sheds light on policies, institutions and processes that enhance governance. We argue in this book that ‘fundamentalism’, ‘ethnicity’, conflict and fragmentation, seen as characteristic of non-Western politics, have political and not necessarily cultural and idiosyncratic origins, and, as such, are amenable to a general explanation and empirical policy analysis.

The States in India have attracted considerable academic and policy attention since the onset of reforms in 1991 in India. The States today are at the centre of debates on Indian federalism and politics (Yadav and Palshikar, 2008; Palshikar and Despande, 2009; Sridharan, 2014; Tillin et al., 2015; Manor, 2015, pp. 73–86; Shastri, 2012; Pai, 2016; Harriss, 1999; Jenkins, 2004; Sinha, 2005; Kumar, 2013). The existing and growing scholarship on newer dimensions of State politics in India points out how the States have become crucial to the formation of coalition governments at the Centre, playing a decisive role in cabinet formation as well as in making many central decisions, including deciding not to implement some. Regional roots of India’s development in recent times as well as the heavy weight of some States in India’s development trajectories have also been examined by scholars in the growing new genre of State politics. The States have also become more autonomous in character, by the fiat of India’s executive federalism, and not necessarily by legislative federalism. They are able to invite investment, both foreign and national, and even formulate novel and innovative public policies that the government at the Centre often adopts as rules of good practice and proliferates in the country as a whole. Some States in India have proved themselves eligible for consideration as favoured destinations for international capital investment. This study builds on similar efforts in its attempt to compare the States, based on the themes of federalism, power-sharing and governance, within a theoretical perspective inspired by neo-institutionalism.

As a contribution to the understanding of politics and governance in India and its States, this comparative study of Bihar, West Bengal and Tripura examines the variations in the levels of governance within a common set of variables defined within a dynamic neo-institutional model of governance. The three cases chosen for this study have the reputation of being ‘difficult’ States of India from the point of view of governance. Their history of protracted conflict, poverty and poor record of human development make them stand out from States like Maharashtra, Gujarat, Karnataka or Kerala who are front runners for the distinction of States of high governance.

The study responds to many State-specific questions. Why was Bihar ungovernable for a considerable period of time till 2005 when the baton passed from Lalu Prasad Yadav to Nitish Kumar? What made Bihar generally more governable again under Nitish Kumar? Why was West Bengal violent for most of the time since 1947 and ungovernable from the late 1960s to 1977? What made West Bengal governable from 1977 to 2011? While the rest of the region was yet to recover from the inflictions of insurgency in India’s North East, what made Tripura a success story of governance, social inclusion and growth? Above all, how do these States cope with the dynamics of India’s neo-liberal reforms? The study delves into these issues on the basis of a general model, with a comparative perspective.

New Leaders, Elite Agency and a Dynamic, Neo-Institutional Model of Governance in India

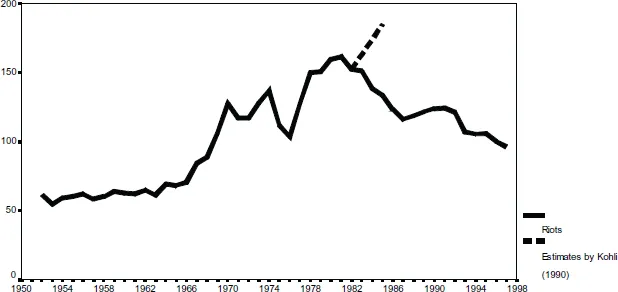

Following independence, India succeeded in achieving a high level of governance compared to the majority of postcolonial states. This record of high governance registered a sharp decline in the 1980s but this decline did not become terminal, bouncing back steadily after reaching its peak in 1985 (Figure 1.1). A similar picture of variance can be seen at the level of India’s regional States (Mitra, 2005). These empirical observations indicate why an analysis of the Indian case offers the opportunity to engage with general and comparative theories of governance, political change and stability.

Though the self-sustaining character of orderly competition for power can be described as the principal tendency of Indian politics, there is considerable variation around it. Elections, while free and fair as a whole, are sometimes sullied by electoral fraud and violence; vicious inter-community riots break long spells of high governance. Once again, the historical trajectory of the introduction of the institutions of liberal democracy holds the key to the understanding of this unusual juxtaposition of order and anarchy. In the liberal, democratic states of the West, the nation was formed before the state structure was crystalized. Unlike the Western ‘nation-states’, modern successor states came into being in South Asia once colonial rule was over. However, these states were not ensconced in stable national communities and robust, mature economies. Nation-building and economic transformation thus became a salient part of the agenda of these nascent states. The institutional buffers and political filters that protect institutions of the state from direct assault by issues of culture and the economy do not exist in non-Western societies. Such is the case in India where riots can break out because of the slightest rumour that discredit the very institutions whose job it is to dispel them. That was the main lesson of Huntington’s analysis of political order in changing societies (Huntington, 1968). The interesting question here is why this phenomenon of mass mobilization outstripping state capacity which often leads to the breakdown of the state has not happened in India. The impression of impending chaos that one gets from Kohli’s early work on the crisis of governability in India had in its background the turbulent 1980s, referred to in the writings of the period as ‘deinstitutionalization’, which saw the rise of terrorism in Punjab, insurgency in Kashmir and Assam and challenges to the modern secular state from religious fanatics. This trend found an echo in Kohli’s forecast of increasing disorder. However, the predictions have not come true as one can see from Figure 1.1. What explains the hiatus between reality and prediction?

Figure 1.1:Riots in India (1950–98).

Source: Mitra (2005), based on data derived from Crime in India (annual) published by Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India. Kohli’s (1990) prognosis is shown in broken lines.

Liberal institutions have followed a different historical trajectory in India compared to Western societies.1 In India, popular democracy, rather than following the transformation from feudal rule to industrial revolution and eventually egalitarian society, has preceded it (Mitra and Singh, 1999). The analysis undertaken here explains this puzzle in terms of a ‘neo-institutional’ model — one which derives the rules of transaction as much from the modern state as from the traditional society — of the role of India’s new social elites in state–society interaction where elite agency, based on policies that safeguard order, welfare of the masses and their core political values, is able to deliver legitimate orderly rule.

Why India?

As a theoretically informed case study, India presents the students of governance with a puzzle. India belongs to a minority of post-colonial states to have sustained, except an interlude of 18 months of the Emergency (1975–77), an orderly political process and the change of government for close to seven decades following independence. The rulers in India at various levels of the federal polity are to be elected at regular intervals by following the rules of the game more or less leaving the army in the barracks. Kohli (2001) quoted from the New York Times dated 8 October 1999 just after the general elections (Lok Sabha) in 1999:

As 360 million Indians voted over the last month, the world’s largest and most fractious democracy once again set a stirring example for all nations….India’s rich diversity sometimes look like an obstacle to unity. But the latest election has proved that a commitment to resolve differences peacefully and democratically can transform diversity into a source of strength.

(Kohli, 2001, p. 1)

More than a mere journalistic hyperbole, the statement served to confirm only many such successful exercises before and after 1999, not only at the national level but also at the State levels, where the issues of diversity and reconciliation of conflicts are more acutely felt. As Yadav has shown, popular participation at the State-level elections has always been higher and increasing. (Yadav, 1996, pp. 95–104) The earlier predictions of balkanization of India’s democracy have proved wrong. Mitra and Singh (2009) have highlighted the success of India’s democracy, making for a different model from that of Europe in its concurrent experiment with democracy and social change. These positive aspects of the success story of India’s democracy merit detailed attention. India’s democratic success is not simply ‘procedural’ (Kohli, 1990) but very substantive. First, a large-scale empowerment of the marginal people has become possible, and better identity prospects for the dalit, women and other such groups have emerged. This has brought to the fore the agency of ordinary people into the very ambit of democracy (Mitra and Singh, 2009, pp. 1–2). Secondly, the number of elected representatives of the people in India as a whole has increased manifold from 5,000 to 3 million over the last seven decades. This increase in the leadership pool — cascading upwards as local leaders rise in the hierarchy of leadership to even higher levels — has added strength to India’s federalism by making for a better linking of the periphery to the Centre. The increase in the number of federal units (now 29 with the formation of Telangana in 2014) has served to empower the distinct cultural identities through India since the 1950s. Third, the above processes have given birth to new ‘social elites’ (ubiquitous in civil society led movements) who have learnt how to combine protest with participation and governance with social welfare and identity (Mitra and Singh, 2009, pp. 4–5). Fourth, the voters have also gotten used to making ‘rational choices’ to change the government, or help to retain it, depending on performance. With the introduction of the universal adult suffrage in 1950, the space has been opened for politics to usher in social and economic change. (Mitra and Singh, 2009, p. 10)

Many critics of the Indian state and its political system from the Left have finally come around to see positive values in India’s parliamentary democracy, institutional innovations and their capacity to generate reform. For example, Chatterjee (1999), often a critic of the failures of India’s liberal democracy, has listed a number of achievements of the post-colonial state in India: a democratic constitution; universal adult suffrage; sustenance of democracy; national sovereignty; equal rights; citizenship; federalism; and growth with equity for most of the period since independence (Chatterjee, 1999, pp. 5–7). Chatterjee argues that the central message to be noted in this regard is, ‘…the condition of our nationhood that modernity and democracy must be fought for and achieved at the same time, together, as part of the same process of struggle and compromise on the site of a political society in which the people of India have managed, after fifty years of chequered experience, to register their presence, albeit with different degrees of effectiveness’ (Chatterjee, 1999, p. 20). Kaviraj has also assessed the positive impact of democracy in India in his contributions and argued that India’s democracy was not merely a sham. He has pointed out that the question of durability of India’s democracy is no longer an issue and warns that the so-called thesis of ‘preconditions of democracy’ continues to colour our very understanding of the reality of India’s democracy (Kaviraj, 2011, pp. 1–25).2

However, the outstanding record often looks unsteady, such as during the decade following the return of Indira Gandhi, the unrepentant author of India’s short-lived but draconian ‘Emergency’ rule (1975–77), to power in 1980 through the ballot box. The corrosion of democratic institutions had started in the 1970s with the decline of the Congress party and the fragmentation of the party system that ensued. The scholarship on Indian politics critically reflected on the theme of deinstitutionalization of Indian politics referring to the period since the 1970s (e.g., Kochanek, 1968; Morris-Jones, 1987; Kothari, 1976); the consequences of a precipitous decline in governance characterized much of the writing on Indian politics in the 1980s (Rudolph and Rudolph, 1987; Morris-Jones, 1987; Kothari, 1989; Manor, 1982, 1988). In sharp contrast to her image of peace and tranquillity, the overall picture of India has been steadily replaced by scenes of rampaging crowds and frenzied mobs taking the law into their own hands through the 1980s. This development questions the images of orderly rule and the democratic resilience of India. Since some of these problems are thought of as cultural obstacles to sustaining rule bound governance, the study examines this question by first drawing on the cross-cultural experience of governance and then exploring it through detailed empirical investigation.

Why West Bengal, Bihar and Tripura?

In India’s new ranking of the States in terms of various Human Development Index (HDI) and flows of Foreign Direct Investment (FDI), these are all ‘backward States’. While Bihar is part of Central India, West Bengal is not; it is semi-peripheral having very long international borders on the east with Bangladesh. Tripura is a peripheral hilly land-locked State sandwiched between long but porous international borders with Bangladesh (in the West and South) and Mizoram on the East. Bihar is mineral rich; its coalfields made major contributions to India’s exchequer. However, it remained one of India’s poorest States and ‘backward’ until 2005. For much of the 1990s, Bihar was identified with the Lalu regime (after Lalu Prasad Yadav, the top leader of the Janata Dal, now RJD, and also of the State power). Even when he was ousted from the Chief Ministership for being accused in the great fodder scam by the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI) and put behind bars, he kept control over office though his wife Rabri Devi who was made the Chief Minister. The Lalu/Rabri regime passed into the hands of Nitish Kumar in 2005 (to 2014) and then again from 2015 (February in a coalition government in which Lalu Prasad kept control over the helm of affairs through his sons). During the Lalu regime, Bihar’s record of violence reached an all-time high. Kohli’s (1990) description of manifold and complex caste–class violence was spectacular:

Examples of the ‘forward castes’ killing the ‘backward castes, or middle caste, of the backward castes killing the forward castes, and of the politicized schedule castes and tribals occasionally killing members of both the forward and the backward castes can all be found. In addition, ordinary criminals, the dacoits, h...