![]()

Chapter 1

Introduction

Thermodynamics in the generalized sense is a branch of natural science in which we study heat, work, energy, their interrelationships, and the modes by which systems exchange heat, matter, and energy with each other and with the surroundings, and convert heat into work, and vice versa. Since all human activities and natural phenomena involve matter and energy of one form or another, the importance of such a science is obvious, and for this reason, it is in the foundations of physical, biological, and engineering sciences. As a matter of fact, thermodynamics owes its genesis to the urgent need at the early stage of the Industrial Revolution in the first half of the 19th century to understand how steam engines work and improve their efficiencies since the efficiencies of such engines had significant economic implications. Such questions are still relevant even to this day in our everyday economic and industrial activities. On the one hand, such a need motivated scientists and engineers to study the properties of steam in particular and gases in general and construct, for example, the steam table. On the other hand, it culminated in the idealization of engines with a reversible cycle by S. Carnot, who made a lasting contribution through his penetrating analysis of how heat engines operate, and his study resulted in his famous principle now known as Carnot’s theorem, although his analysis was based on the caloric theory of heat which was proven to be an incorrect notion of heat. Later pioneers such as R. Clausius and W. Thomson (Lord Kelvin) adopted the correct notion of heat — in which heat is regarded as a form of energy — and developed a correct theory by retaining truthful features in Carnot’s exposition and adding something new. Through the efforts by them and their followers, the science of thermodynamics was born in the second half of the 19th century. The subject was refined, especially in an important way, by J. W. Gibbs through his well-known work on heterogeneous equilibria. The modern form of the science of thermodynamics, laid on the foundations shaped by the efforts by S. Carnot, Count Rumford (Benjamin Thompson), J. R. Mayer, R. Clausius, W. Thomson, H. Helmholtz, and J. W. Gibbs, among others, has been shaped by numerous other researchers, but its applications to chemical and chemical engineering problems owe a great deal to the works by M. Planck, W. Nernst, F. Haber, and G. N. Lewis and his school to name a few. The works of Max Born and C. Caratheodory have given equilibrium thermodynamics another mathematical aspect through Caratheodory’s theorem, which opens up a geometrical viewpoint to thermodynamics. However, we will not discuss this line of thought in this work.

It is now generally believed that all natural macroscopic phenomena occur in full conformation to the laws governing thermodynamics. Although the subject of thermodynamics has been around in science over 160 years by now, since the pioneers in thermodynamics limited the development to reversible processes and thus to systems in equilibrium, it is not closed, but is still developing. It is therefore worth a serious study, especially since irreversible phenomena are not sufficiently well understood as yet from the standpoint of the laws of thermodynamics, especially, if irreversible processes occur far removed from equilibrium.

From the viewpoint of thermodynamics of irreversible processes, equilibrium thermodynamics — which, more precisely, should be called thermostatics and we are going to study here — is merely dealing with systems at a singular state of thermodynamic equilibrium. Since there are no macroscopically discernable processes occurring in equilibrium systems, equilibrium thermodynamics deals with idealized reversible processes and thus is not capable of describing what is happening in the real system over a finite time span and over space; rather, it is only able to tell us of the possibilities of that particular event as far as the laws of thermodynamics are concerned. The description of the process over a finite span of time and space is in the realm of irreversible thermodynamics, which is still in the developing stage at present. The basic reason that the subject of equilibrium thermodynamics is useful and powerful despite the idealized reversible processes studied in it is that some of macroscopic thermodynamic properties of a system, which is going through irreversible processes, can be related to the complementary quantities computed from the reversible processes as will be shown later as we develop the subject in greater detail because there is a state function of thermodynamic state variables for the system even if the processes are irreversible. This state function extends the notion of the equilibrium entropy into the domain of irreversible processes. The existence of such a state function — called calortropy — lifts thermodynamics from the level of studying only idealized reversible processes, as in equilibrium thermodynamics, to a level of using a more insightful and powerful mathematical tool for studying various aspects of irreversible behavior of the system. We will elaborate on this point in the chapters dealing with the second law of thermodynamics and in nonequilibrium part consisting of Chapters 19–22 of this book.

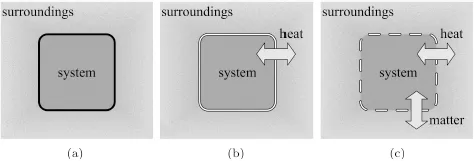

Since we are going to use various terms in our study, we fix their meanings by introducing the following system of terminology. A system is that part of the physical world which is under consideration, and the rest of the physical world is called the surroundings.

When a system exchanges mass, heat, work, and any other forms of energy with the surroundings, it is called an open system (c). When a system does not exchange matter but energies with the surroundings, it is said to be a closed system (b). If a system has no interaction whatsoever with the surroundings, it is called an isolated system (a). It is possible to regard the system and the surroundings together as an isolated system. We will find it convenient to do so for some cases (Fig. 1.1).

Thermodynamics is concerned with gross observables of a macroscopic system and their interrelationships. Since according to the atomic theory of matter, a macroscopic system consists of an enormous number of atoms and molecules not counting elementary subnuclear particles, a microscopic description of the macroscopic system would entail a knowledge of an enormous number of microscopic variables. However, a large number of molecules in an assembly exhibit as a rule a collective behavior, which may be described by a small number of variables called macroscopic variables or macroscopic coordinates. A macroscopic variable (coordinate) is an observable whose determination requires only measurements, over time spans long compared with periods of thermal motion, that take averages of microscopic variables over regions containing a large number of molecules and involving energies large compared with individual energies of atoms and molecules. Pressure, volume, temperature, internal energy, and so on, are examples of such macroscopic variables.

Fig. 1.1. The system and surroundings — universe. Panel (a) is an isolated system; (b) is a closed system; (c) is an open system.

We often speak of thermodynamic properties. These are termed as the properties of the system which describe its macroscopic coordinates. Thermodynamic properties are classified into two categories. If a thermodynamic property is independent of the mass of the system, then it is called an intensive property. Examples are pressure, temperature, concentrations, and molar properties. If a thermodynamic property depends on the mass of the system, it is called an extensive property. Examples are the volume, energy, entropy, and so on, of a system which increase in proportion to the mass of the system. Intensive and extensive properties (variables) often appear as conjugate pairs of variables in thermodynamics. We may take the examples of pressure and volume, and temperature and entropy for such conjugate pairs of thermodynamic variables. Intensive properties, however, may vary with position in the space as do the extensive variable if the system is not homogeneous in space. If the intensive properties are continuous functions of position throughout the system, then the system is called homogeneous, and if they are not continuous functions of position throughout the system, then the system is called heterogeneous. For example, a system is heterogeneous if the density changes discontinuously across the boundary of two homogeneous regions of the system. Such homogeneous regions of a heterogeneous system are called the phases of the system. An example for heterogeneous systems is a system of water and ice, and in this particular case, there are two phases in the system of a single component.

We will often speak of a thermodynamic state. The thermodynamic state of a system is defined by its intensive properties. They may or may not change over space and time. A system is said to be in a state of thermodynamic equilibrium if (a) the thermodynamic state of the system does not change in the time duration of the observation performed, and (b) no material or energy flux exists in its interior or at the boundaries with the surroundings. Otherwise, the system is in a state of nonequilibrium. In equilibrium thermodynamics, we examine systems which are in a state of thermodynamic equilibrium.

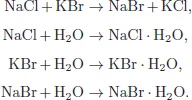

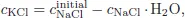

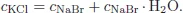

A system may be composed of a single component or more than one component. In the former case, the system is called a pure system and in the latter case, it is called a mixed system or simply a mixture. In a mixture, there may arise the question as to the number of independent components of the system: it is defined by the minimum number of chemical species from which the system can be prepared in each phase of the system by a specified set of physico-chemical procedures. A practical way of determining the number of independent components is the total number of components minus the number of distinct chemical and other restrictive conditions such as chemical reactions and charge neutrality conditions. For example, consider a system formed when NaCl, KBr, and H2O are mixed. If KCl, NaBr, NaBr·H2O, KBr·H2O, and NaCl·H2O are isolated on chemical analysis, the distinct chemical reactions are

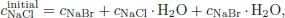

If the concentration of species i is denoted by ci then since there hold the relations for concentrations

and

where cNaClinitial is the initial concentration of NaCl, we find

This means that the number of independent components is (8 − 1) − 4 = 3 in this case.

In Chapter 2 of this book, the notions of temperature, work, and heat are discussed. In Chapter 3, the first law of thermodynamics is discussed together with thermochemistry, which deals with measurements of heat released or absorbed by the system. In Chapter 4, the second law of thermodynamics is discussed. This important principle, which was literally enunciated by Lord Kelvin and R. Clausius, was given a mathematical representation in the form of inequality now known as the Clausius inequality. In this work, the Clausius inequality will be replaced by an equation as a general mathematical representation of the second law of thermodynamics, which remains valid even if there are irreversible processes present in the system. The said mathematical representation of the second law of thermodynamics permits us to develop the thermodynamics of irreversible processes in a general context. For this purpose, we introduce the notion of calortropy. This part of the treatment of the second law of thermodynamics sets the present work apart from the conventional methods used in other works available in the literature on thermodynamics. The distinctive point of the new quantity is that it is the extension to nonequilibrium of the notion of equilibrium entropy that was originally introduced by Clausius for reversible processes only. By the accomplished extension, we are now provided with the starting point of a theory of irreversible processes in a general form, and even the equilibrium thermodynamics of Clausius is provided with a window through which we can glimpse into the world of irreversible phenomena even if one studies just the reversible process associated with the irreversible process in question. The nonequilibrium extension of the Clausius entropy is given the new term calortropy, which means heat evolution. This extension frees us from the shackles of entropy defined for equilibrium only, and equilibrium thermodynamics consequently becomes easier to comprehend than otherwise.

In the rest of the book, we treat the conventional subjects of equilibrium thermodynamics, which are commonly discussed in courses on thermodynamics. The subjects covered are thermodynamics of gases, liquids, and solutions, heterogeneous equilibria, chemical equilibria, strong electrolytes, galvanic cells, and the Debye–Hückel theory of strong electrolytes, which is the only concession we make to discuss a statistical treatment of macroscopic phenomena. We will also discuss the thermodynamics of systems subject to electromagnetic fields and the thermodynamics of interfacial phenomena.

In nonequilibrium part of this book, we present a summary of a general theory of thermodynamics of irreversible processes in systems removed from equilibrium at arbitrary degree in Chapter 19. In Chapters 20–22, we provide examples for the applications of the general theory to linear irreversible processes occurring in the vicinity of equilibrium; to nonlinear irreversible phenomena such as non-Newtonian flow, non-Fourier heat conduction, nonlinear electrical conduction; and to nonlinear phenomena involving spatial and temporal oscillatory phenomena in chemically reacting medium. These are some examples that we encounter in recent chemical and physical experiments and in engineering and biological sciences, for which thermodynamics of irreversible phenomena is not only relevant but also of importance. These chapters are meant to introduce the readers to the thermodynamics of irreversible phenomena in macroscopic material systems.

We believe that thermodynamics is a subject that should be studied without an intrusion by a molecular theory approach (i.e., statistical mechanics) because it is a subject that allows us to make deductions with regard to macroscopic properties of matter without reference to the molecular picture of matter and eventually serves as the ultimate aim of molecular theory of macroscopic matter, which is developed by means of statistical mechanics on the basis of molecular theories of matter. Mixing thermodynamics and statistical mechanics tends to confuse important issues regarding thermodynamics, which is distinctive from the molecular theoretic treatment of macroscopic properties of matter used in statistical mechanics and the various i...