![]()

Chapter 1

TNF Superfamily in Inflammation

Marisol Veny*, Richard Virgen-Slane* and Carl F. Ware*

1.Introduction

1.1.Discovery of TNF and lymphotoxin

Studies of the tumor necrosis factor superfamily (TNFSF) can be traced back to the 1800s, when it was found that acute inflammation induced by bacterial extracts could trigger necrosis of tumors. Nearly two centuries later, activated lymphocytes in culture were shown to produce a cytotoxic factor for tumor cells,1 named Lymphotoxin (LT)2 and macrophages secreted a cytotoxin that caused hemorrhagic necrosis of tumors, named Tumor Necrosis Factor (TNF).1–3 Although these host-derived anti-tumor factors were greeted with great enthusiasm, knowledge of their true physiologic functions awaited advances in protein chemistry and molecular biology.

The cloning of the genes for LT4–6 and TNF7–10 revealed significant shared sequence homology.4,11,9 Additionally, the recombinant proteins displayed similar biological activities4,9 and bound the same two cell surface receptors, now referred to as TNFR1 and TNFR2.12–17 Thus, LT and TNF were recognized as the founding members of a superfamily of homologous ligands, and their specific cell surface receptors forming the TNF receptor superfamily. The similarities in TNF and LT and their receptors suggested redundancy of function.18 This outlook changed with the discovery of two important differences in the properties of TNF and LT. The first key difference, which prompted the renaming of LT (also called TNFβ) to LTα, was its interaction to form a novel ligand with lymphotoxin-β (LTβ) forming a heterotrimeric complex LTα1β2.1,9 Later, a receptor specific for LTα1β2, but not TNF, was discovered and named the LTβ receptor (LTβR).20 The second major finding was that mice deficient in either one of the genes LTα, LTβ, or LTβR fail to develop lymph nodes and other secondary lymphoid organs.21–23

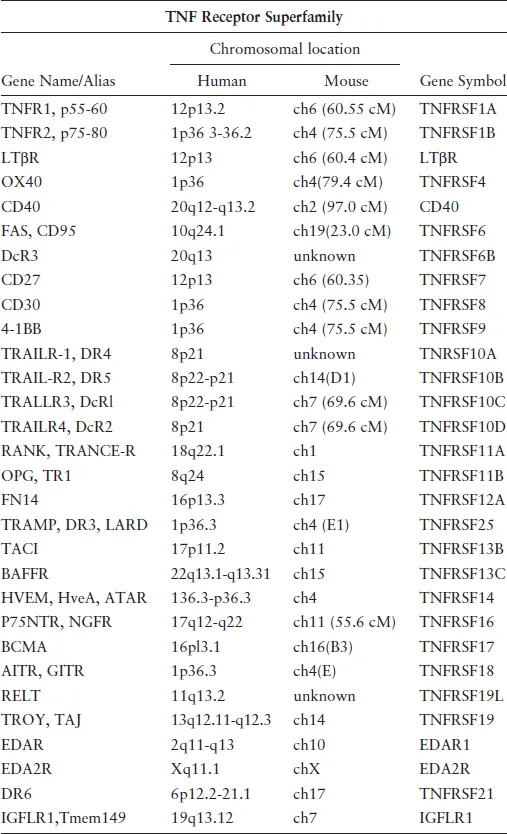

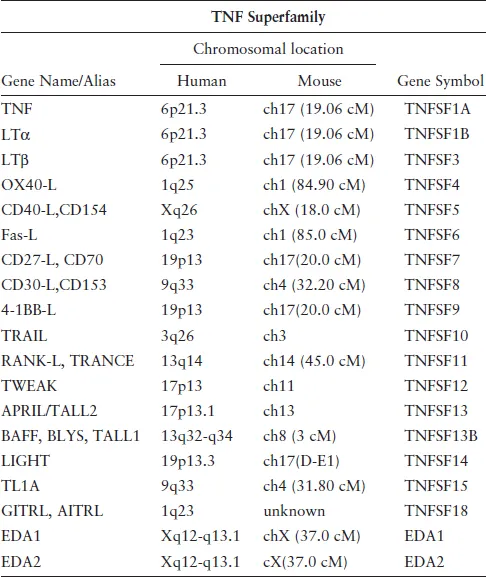

Several more receptors (Table 1) and ligands (Table 2) were discovered as members of these superfamilies, revealing the scope of these ligand–receptors in animal physiology. Among the receptors critical for immune responses include CD27,24 CD40,25 CD30,26 OX40,27 4-1BB,28 and Fas.29 Members of the TNFRSF also play important roles in the physiology of skin, bone, and nervous system, and orthologous genes were found in the genomes of large DNA viruses including poxvirus30 and herpesviruses.

1.2Description of TNFSF proteins

1.2.1.TNFSF ligands

With the exception of TL1A31 and FasL,32 the expression of TNFSF ligands is restricted to cells of the immune system, including dendritic cells (DC), activated lymphocytes, and myeloid cells. TNF-related cytokines are type II transmembrane proteins with short cytoplasmic tails (15–25 amino acids) and larger extracellular regions (~150 amino acids). They contain a signature β-sheet sandwich, known as the TNF homology domain, which facilitates trimer formation and receptor binding. The ligands have highly conserved tertiary structures,33–37 despite only limited sequence homology (<35%). Linker regions between the β stands are variable and form specific contacts with the receptors. Many TNFSF ligands can form homotrimers, and some also assemble as heterotrimers; examples of the latter group are LTα with LTβ19 and APRIL with BAFF.38 Alternatively spliced variants of TNFSF ligands produce molecules with additional functionalities. These include the fusion of TWEAK and APRIL to form TWE-PRIL39 and the cytosolic form of LIGHT.40

Table 1.TNFSF receptors.

Table 2.TNFSF ligands.

1.2.2.TNF receptors superfamily

Unlike the ligands, TNFRSF expression is not restricted to cells of the immune system. The ligand-binding extracellular region of the receptors contains a cysteine-rich domain which is typically composed of six cysteine residues forming three disulfide bonds. Most TNFRSF members are type I transmembrane glycoproteins (extracellular N-terminus) and can be further segregated into two groups based on whether the intracellular domain (i) contains a death domain (DD) or (ii) binds TRAFs directly. Several TNFRSF members (e.g., TRAILR3) are membrane anchored via a glycolipid linkage that binds ligand but does not propagate signaling, and some receptors can be proteolytically released to generate soluble forms.

1.2.3.Ligand-receptor binding models

While TNFSF receptor–ligand binding is in general monotypic, some members have multiple partners41 with non-redundant cellular responses that are unique for each ligand–receptor pair. The binding affinities are in the high picomolar to low nanomolar range. TNFRSF members are activated by aggregation, which is induced physiologically by interaction with their trimeric ligands. This activating mechanism not only explains why bivalent anti-TNFR antibodies can act as receptor agonists42 but also clarifies why overexpression of TNFR, which has a propensity to self-associate,43 results in ligand-independent signaling.

Signaling through ligand–receptor complexes can be influenced by the physical state of the ligand, whether membrane-bound or secreted (e.g., TNF). For example, membrane FasL induces apoptosis in peripheral T cells, but this activity is blocked by the secreted protein.44 Changes in the expression of TNFSF members in response to environmental factors can also affect signaling. This has been observed for FasL expressed on endothelial cells, which is downregulated in response to TNF during inflammation. This is particularly important in inflammation, because under normal conditions, FasL induces leukocyte apoptosis to prevent tissue infiltration.45 Further regulation of TNFR signaling is achieved by controlling ligand availability. Thus, decoy receptors such as DCR1, DCR2, DCR3, and OPG can inhibit signaling by sequestering the ligands.46

The interaction between a TNFSF ligand and its cognate receptor induces one of two outcomes: the cell will either undergo apoptosis via formation of the death-inducing signaling complex (DISC) or activate transcription factors to promote survival. How this is achieved will be discussed in the signaling pathways section further below.

1.2.4.The lymphotoxin and tumor necrosis factor network

The complexity of interactions and outcomes of the TNFSF members is well exemplified by the network that LT and TNF form with their different receptors (Figure 1).

TNF, LTα, LTβ, and LIGHT define the immediate group of TNF-related ligands that bind four cognate cell surface receptors with distinct but shared specificities. TNF and LTα both bind two receptors, TNFR1 and TNFR2. The heterotrimeric LTα1β2 complex binds the LTβR, which also binds LIGHT. LIGHT also engages HVEM (Herpesvirus entry mediator; TNFRSF14), which acts as a ligand for Ig superfamily members, BTLA and CD160.47 Two distinct human herpesviruses, herpes simplex virus and cytomegalovirus (CMV), target the HVEM-BTLA pathway using different mechanisms (Fig. 1).48,49

This pattern of shared utilization of ligands and receptors together with bidirectional signaling defines a complex co-stimulatory and inhibitory network. HVEM forms a switch between positive cosignaling through LIGHT-HVEM interaction and inhibitory signaling through B- and T-lymphocyte attenuator (BTLA). LIGHT and LTα bind HVEM at a distinct site from BTLA and CD160, yet all four ligands can activate the HVEM-NF-κB pathway to promote cell survival and differentiation.50 In contrast, reverse signaling by HVEM engagement of BTLA restricts T and B cell proliferation by a direct inhibitory mechanism via the ITIM module in BTLA that recruits SHP1/2 tyrosine phosphatase, limiting antigen receptor activation.51,52 UL144 of human CMV binds BTLA, but not LIGHT or CD160, selectively mimicking the inhibitory pathway of HV...