![]()

Chapter

1 | Managing Indonesian Haze: Complexities and Challenges |

Asit K. Biswas

Distinguished Visiting Professor, Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy,

National University of Singapore

[email protected] Cecilia Tortajada

Senior Research Fellow, Institute of Water Policy,

Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy, National University of Singapore

[email protected] Introduction

Transboundary air pollution is not a new phenomenon. It has existed for centuries in one form or another. Causes for this pollution could be both natural and man-made. However, prior to 1960, it was not a serious issue since population levels, urbanization rates and the extent of industrial and agricultural activities were rather low. Equally, prior to 1960, all types of environmental pollution were generally accepted by societies to be prices that had to be paid for economic progress. In addition, the health, economic and environmental costs of air, water and land pollution were neither properly known nor fully appreciated. Thus, if there was a conflict between economic growth and environmental pollution, it was routinely resolved in favor of economic growth.

The situation started to change around 1970 when many people in the industrialized world started to realize and appreciate the increasing costs of environmental pollution that had significantly adverse impacts on the human and the ecosystems health. The smog of the 1950s in major cities like London, Los Angeles and Tokyo made their inhabitants question if unfettered economic growth, at the cost of environmental deterioration, is a desirable long-term societal policy option. Shortly thereafter, a nascent environmental movement started. It began to gain momentum and flexed its muscles during the post-1970 period.

Transboundary air pollution first burst into global consciousness during the 1960s when some Swedish and Norwegian scientists noted that a large number of their lakes were showing increasing acidity. This resulted in a steady increase in fish kills and serious negative impacts on many other species. Aquatic biodiversity was declining. Forests were also adversely affected.

The culprit was found to be acid rain whose sources were outside Scandinavia. Acid rain was being caused by sulfur dioxide and nitrogen oxides emitted by factories in the United Kingdom, West Germany and several East European countries which reacted in the atmosphere with the water droplets in the clouds. The net result was that rainfall in Sweden and Norway contained higher concentrations of nitric and sulfuric acids, which started to take its toll on aquatic and territorial ecosystems by acidifying lake waters.

During the late 1960s, Sweden tried very hard to convince the emitting countries of the problems they were causing in Scandinavia and attempted to persuade them to reduce their atmospheric emissions. Being unable to move bigger countries like the United Kingdom or Germany to reduce their emissions, Sweden offered to host the 1972 United Nations World Conference on the Human Environment in Stockholm. The hidden agenda behind this offer was to bring the problem of transboundary air pollution and the harm it was causing to Sweden and other Scandinavian countries to global attention.

This strategy succeeded in increasing the global awareness of this issue (Biswas and Tortajada, 2013) and also internationalizing and bringing it to a major United Nations forum. This Conference and subsequent efforts led to the adoption of the Convention on Long-range Transboundary Air Pollution in 1979 (UNECE, 1979). It entered into force in 1983. This has now been ratified by 53 members of the UN Economic Commission for Europe.

As a result of this legally binding treaty, collective efforts of the emissions of harmful air pollutants have been reduced by 40 to 80 percent since 1990. Sulphur emissions have declined very significantly. This meant that acid rain problems in Europe had been mostly consigned to the dustbin of history, and forests are healthier.

Some 30 years later, transboundary smoke pollution became an important concern in most Southeast Asian countries, except for Myanmar and Laos, and some Pacific island areas like Guam, Palau and Northern Mariana Islands. They are affected by haze because of forest and vegetation clearance by fire, primarily in the Indonesian provinces of Sumatra and Kalimantan. This clearance is to ensure increasingly more and more land is available for expanding the area for palm oil cultivation to meet the burgeoning global demand.

The main difference between the Swedish and the Indonesian cases is that acid rain had very limited impact on the emitting countries like United Kingdom and Germany. In contrast, the Indonesian haze is having the most severe health, economic and environmental impact on the country from where it originates, as well as on its neighbors. Even then, it has proved to be an intractable problem to solve.

Indonesian haze: Background to the problem

Palm oil is not indigenous to Asia. The Portuguese first discovered palm oil in the 15th century in Africa. They found that the small farmers of West African rainforests used palm oil for soups and baking. Following this Portuguese discovery, palm oil gradually became an important provision for trading caravans and slave ships.

In an Asian context, the British administrators first introduced oil palm in the 1830s to India. They planted some seedlings in the botanic garden of Kolkata. Trial commercial planting was started later in Kerala. They did not make much headway.

In Indonesia, oil palm first arrived in 1848, via Amsterdam. Like in India, four seedlings were planted in the botanic garden of Bogor. They were initially considered to be ornamental plants and were planted in tobacco estates and roadsides for beautification purposes.

Commercial plantation for palm oil in Indonesia started in 1911, in Sumatra, by a Belgian agronomist, Adrien Hallet. Hallet had interest in rubber plantations in the then Belgian Congo. In 1912, Henri Fauconnier, a Frenchman, bought some seedlings from Hallet. He established the first commercial plantation in Malaysia, at Tennamaram Estate, Selangor. Having failed at making a successful coffee plantation, Fauconnier thought he would have better luck with palm oil.

After the Second World War, rubber plantations ran into severe headwinds because of rapidly falling demands. Large-scale plantation owners looked at crop diversification, and oil palm appeared to be a good potential alternative. An intensive agricultural research and breeding program was started in Malaysia to assess the economic feasibility of palm oil.

Because of good agro-climatic conditions, oil palm cultivation has always been a good prospect for Malaysia and Indonesia. However, it has had a rather checkered development history in Indonesia. Its development was in the doldrums after Indonesia’s independence in 1945. Dutch plantation owners no longer received financial and political support from the colonial government. Some two decades later, in 1967, commercial plantations picked up some steam under its second President, Suharto. Investments were made through state-owned enterprises, with financial support from the World Bank.

During the 1980s, oil palm plantations received a major boost following a finding that these trees are pollinated by a tiny weevil, and not by wind, as previously thought. Introduction of these pollinating weevils in Malaysia and Indonesia dramatically reduced the cost of pollination which earlier was being done by human hands. In the 1980s, Malaysia became the world’s largest producer of palm oil.

With an increasing global population and more and more people having steadily higher incomes, their dietary habits and requirements have changed as well. The global demand for edible oils and fats have steadily increased following the Second World War. With this ever increasing demand, global production of all types of oil seed crops have increased concomitantly as well.

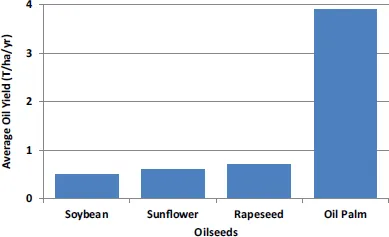

Oil palm is the most efficient oilseed crop in the world. Its average oil yield per hectare is about 6–10 times that of soybean, sunflower or rapeseed (Figure 1). At present the most efficient oilseed farmers can get as much as 8 metric tons of oil per hectare. Thus, not surprisingly, even though oil palm accounts for less than 6% of total area in which ten of the world’s most important major oil seed crops are cultivated, it accounts for nearly 32% of global oil and fat outputs.

Currently palm oil is Indonesia’s second most successful agricultural product, after paddy rice. It is now by far the country’s largest agricultural export earner, accounting for nearly 11% of the country’s total export earnings. For the rural poor, it is a most important source of income and survival. In 2015, 54% of the Indonesians lived in rural areas. Thus, oil palm cultivation has been one of the important pillars for economic development and poverty alleviation policy for the country in the recent decades.

Figure 1. Average Yield of Oilseeds Crops

Source: Oil World (2013).

Development of oil palm cultivation truly picked up steam when Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono was re-elected as the Indonesian President. In his inauguration speech in 2009, he expressed his determination to improve the country’s welfare and reduce poverty. These objectives, he said, would be achieved through “economic development based on competitiveness of natural resources management and human resources development” (Jakarta Globe, http://jakartaglobe.beritasatu.com/archive/sbys-inaugural-speech-the-text/).

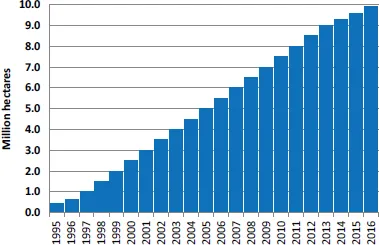

President Yudhoyono’s plan led Indonesia to become the largest palm oil producer country by far in the world. In 2016, its annual production was estimated at 35 million metric tons (MT). The second largest producer, Malaysia, produces 21 million MT, and the third, Thailand, produces 2.3 million MT, only a small fraction of Indonesia. The phenomenal increase in production meant that the land area under oil palm cultivation during 1995–2016 expanded very significantly as well. This steady increase in area is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Indonesian Oil Palm Cultivated Areas, 1995–2016

Source: USDA (2015).

Under Yudhoyono’s Presidency, palm oil production became one of the main pillars of economic development and poverty alleviation, especially for the rural areas. In 2008, just before he was elected President, smallholders accounted for nearly 40% of the land, some 1.2 million ha, where oil palm was cultivated. Some 3.5 million households, or about 15 million rural Indonesians, made a living out of growing oil palm. The number of people involved in palm oil supply chain activities (off-farm) was even greater. Thus, palm oil was already an important economic activity in the rural areas before he started his second term as the President.

The plan for agricultural expansion of oil palm was truly ambitious. It proposed to increase the cultivated area to 10–12 million ha by 2020. This would produce 40 million MT of crude palm oil. This expansion was expected to generate new employment opportunities for 1.3 million households. If so, it would reduce the total number of poor people by at least 5.2 million, from an estimated 30 million in 2009.

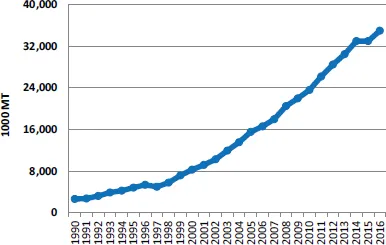

Favored by government policies, economics of production, commercial logic, and accelerating global demands, Indonesia overtook Malaysia as the world’s largest commercial palm oil producer. The increase in palm oil production in Indonesia, during the 1964 to 2016 period, has been truly phenomenal. In 1964, Indonesia produced only 157,000 MT of palm oil. It increased to 752,000 MT in 1980, to 2.65 million MT by 1990, 8.3 million MT in 2000, 23.6 million MT in 2010 and 35.0 million MT by 2016. The growth in production is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Indonesian Palm Oil Production

Source: Index Mundi (2016).

Not surprisingly this phenomenal growth in palm oil cultivation during the post-1990 period (Figure 3) has been possible due to an exponential increase in land areas where oil palm had been planted (Figure 2). During the 1995 to 2016 period alone, the area planted increased by some 20 times, and quantity produced by some eleven times. Viewed from any perspective, these growth statistics have been phenomenal.

Implications of this growth

The exponential increase in land area used for oil palm cultivation in Indonesia has been possible primarily through the clearance of primary and secondary forests and other vegetative growths. This of course is not new. As the population of Indonesia has increased, there has been progressive deforestation, so that enough land could be made available for all kinds of human activities, including agriculture. In Indonesia’s case, the pressure on land clearance has been intense and sustained, especially during the last 50 years, because of oil palm, rubber and timber plantations. The problems have been further exacerbated by the absence of any reasonable land use planning and absence of good environmental policies and management practices.

The population pressure in Indonesia can be visualized from the following facts. In 1960, its population was 88.69 million. By 2015, it had increased to 255.46 million. In other words, in a period of only 55 years, its population increased by about three times. In 1960, 85% of its population (75.38 million) lived in rural areas. By 2015, while this percentage had declined to 46%, in absolute number its rural population was much higher (117.51 million) than what it was 50 years ago. An overwhelming percentage of the rural population still depends on agriculture to earn a living, and still live below the poverty line.

Spurred by steadily increasing global demands for palm oil, timber and rubber, Indonesia has progressively lost forest cover to agricultural development due to deliberate and intentional burning (Quah, 2002). Much of this forest loss has taken place in the lowlands of Sumatra and Kalimantan (Mayer, 2006). This region witnessed an annual deforestation rate of nearly 3.5% during the 1990s. Hansen et al. (2009) have estimated that between 1990 and 2005, this region lost nearly 40% of its forest cover. Margono et al. (2014) have estimated that more than 6Mha of deforestation took place in Indonesia between 2001 and 2012. By 2012, deforestation in Indonesia exceeded that of Brazil.

Several recent analyses have found that the latest trend has been to move away from the clearance of dryland forests to secondary and peatland forests (Margono et al., 2014; Miettinen et al., 2011). Fire is used extensively to clear peatland and degraded forests. Herein lies the genesis of a major transboundary air pollution problem because of economic necessity of cultivating oil palm in Indonesia.

Peatland forests are generally protected by the presence of high water tables. In order to reclaim these lands for planting oil palm trees, water has to be drained so that vegetation growth can be cleared by fire. As the water table declines, forests and vegetation become increasingly susceptible to burning, as well as to oxidation. This burning has now become the primary source of national and transboundary air pollution. Oxidation does not have any perceptible impact on air quality.

Peatlands are major carbon sinks and can store up to 20 times more carbon dioxide compared to tropical rainforests on normal mineral soils. Thus, when they are burnt, they become major emitters of CO2 as well as other undesirable gaseous pollutants like CO, CH4, NOx and NH3. Minister Zulkifli (2015) of Singapore noted during his speech at UNFCCC COP-21 meeting in Paris that peat fires, in 2015, in Indonesia, released over one giga-ton of CO2 into the atmosphere. These emissions, only over a few months, were higher than the total annual carbon emissions of a major industrialized country like Germany.

This burning, in addition to producing greenhouse gases, contributes to extensive generation of smoke, including particulate pollution, which in turn contributes to serious haze problems in Indonesia and neighboring countries every summer.

The direct linkages between the demand for plantation products, global economy and deforestation can be appreciated by the fact that deforestation rates were significantly lower during the economically lean years of 1999–2001. During this period, the demand for commodities like palm oil was not robust. As the global economy improved, demand increased, and prices of palm oil and other commodities firmed as well. This, in turn, increased the production of palm oil in Indonesia.

Traditionally, forests and degraded lands are mostly cleared by slash-and-burn agriculture. This has been the normal practice in the country for centuries. The ...