![]()

Chapter 1

Introduction

The purpose of this book is to introduce the economic research on enterprises of small and medium scale. This has been a topic of active economic research for about a generation. In earlier economics, there was little or no special study of small business, probably because economists thought of small business as the norm. Agricultural enterprises, which are typically small, were the special study of agricultural economics. Otherwise, it seemed that it was “big businesses” that needed specialized study — monopoly and oligopoly. Much was learned about these enterprises in the specialized studies of industrial organization and public utilities. These studies showed how the abstract idea of “the firm” in economic theory could give way to a more detailed, empirical understanding of business organizations. In the late 1980s, some economists began to study small business in a similar way. The journal Small Business Economics began to be published in 1988. In the quarter century that has followed, a great deal has been learned, some of it built on work that had already been done before 1988 and proved particularly valuable for the study of small- and medium-scale businesses, and much of it novel. The purpose of this book is to convey the results of this research in a form accessible to undergraduate students in economics and others with some preparation in economics. The focus will be on non-agricultural small and medium enterprises (SMEs).

Why study small businesses? First, there are a lot of them. There are many more small businesses than big businesses. In the United States, about 99.75 percent of businesses are “small.” Over the years, in the United States, small businesses have employed about half of the work force and produced about one-third of GDP. There is reason to believe that small businesses often face different conditions than larger businesses. Small businesses are more likely to be located in rural areas. Small businesses tend to be in different industries than large businesses: industries in which increasing returns to scale are less important. Finally, but most importantly, government policies often give small businesses special consideration.

1.Small and Medium Enterprises as a Topic for Economics

In the first issue of Small Business Economics, Brock and Evans wrote (1989, p. 7) “About 13 million of the 17 million corporations, partnerships, and sole proprietorships that filed (United States) federal tax returns in 1986 had no employees other than their owner. All but approximately 10,000 of the 4 million businesses with employees had fewer than 500 employees.” We will see that the numbers of firms have continued to grow in the interim. They continue (p. 7)

Small-business economics seeks to better understand why firms come in different sizes, how and why firm behavior varies with size, what determines the formation, growth, and dissolution of small firms, the role of small firms in the introduction of new products and the evolution of industries, and the dynamic relationships among small firms and macroeconomic variables such as output and employment.

A first step is to get a better idea of just what we might mean by “small business.” How is the business scale best measured? Should we focus on sales, capital value, employment, or use different measures for different purposes? Where can we find the boundary between small-, medium-, and large-enterprise scales? Certainly, the range given by Brock and Evans includes enterprises that will operate very differently. A self-employed businessman without any employees is a very different kind of operation than a firm with 20 employees, and the firm with a few hundred employees is a different kind of operation yet again.

The most common measure of the size of the enterprise is the number of employees. This has the advantage that it is relatively easily comparable. If one company sells tractors and the other sells cheesecakes, it will be easier to compare the number of employees of the tractor company and the number of employees of the cheesecake company than it is to compare the output of tractors to the output of cheesecakes! On that basis, we will treat the number of employees as the principle measure of the size of the firm. From time to time, for specific purposes, we will also measure the size of the firm by revenue or capital value.

2.How Small is Small?

The U.S. Small Business Administration serves businesses with 500 or fewer employees, for most purposes. At the other extreme, about three-quarter of businesses have no paid employees. They employ the proprietor (maybe part-time) and, in some cases, family labor. In the United States and some other countries, firms with fewer than 50 employees are excluded from certain regulations as “small businesses.” For other regulations, there are different thresholds below which the enterprises are excused as “small businesses.” Thus, what is a “small business” depends on the purpose for which we ask the questions. We should probably say “small and medium enterprises” (SMEs) for enterprises with 500 or fewer employees.

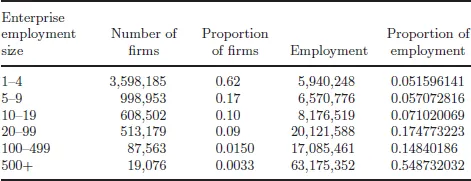

Caruso (2012) writes “In 2012, large enterprises employed 59.9 million people (51.6 percent of all employees), very small enterprises employed 20.4 million people (17.6 percent), small enterprises employed 19.4 million people (16.7 percent), and medium enterprises employed 16.3 million people (14.0 percent).” For these statistics, very small enterprises have fewer than 20 employees, but do have employees other than the owner, small enterprises have 20–99 employees, medium enterprises 100–499 and large enterprises 500 or more. This book will use those categories whenever possible. This is summarized in Table 1. But, as we will see, other studies use other break points. Table 2, based on data from the U.S. Bureau of the Census, presents some data for the United States in 2014. (Data for 2016 is not yet available as I write.)

Table 1. Categories of SMEs.

| Microenterprise | Self-employed part time |

| Non-employer | No paid employees |

| Very small employers (VSE) | 19 or fewer paid employees |

| Small employers (SE) | 20–99 employees |

| Medium-size enterprise (MSE) | 100–499 employees |

Table 2. Businesses of Different Sizes in the United States in 2014.

In studying small business, it is important to distinguish between the firm and the establishment. Some firms have multiple locations — establishments — so the establishment may be small even if the firm itself is medium or large. Headd (2000, p. 13) writes, “First, with regard to small businesses, establishment data . . . can result in incomplete figures, because many small establishments are parts of large businesses.” Franchises generate a slightly different problem. Most employees that we see in a franchised operation such as a McDonald’s® restaurant are not employees of McDonald’s, a large business, but of the franchisee, which will often be a small business.

3.Non-Employer Businesses

Many of our statistics refer only to employer firms, since they are classed by number of employees. However, about three-quarters of all business firms in the United States have no employees. The same is true of Britain (BMG Research, 2013): “The 2012 Business Population Estimates calculated that there were 4,794,105 businesses in the UK private sector. . . . However, 74 percent of these businesses had no employees. . . .” (p. 13). These are self-employed individuals and some family firms that deploy only the labor of family partners in the enterprise. I think of a firm I have done business with in which the work (paving) is done by a father and son and the mother is the telephone receptionist, scheduler and bookkeeper. At the other extreme, some businesses employ a proprietor only part-time. After my sister’s retirement, she sold some craftwork but did not work at that full-time.

Here are some data on non-employer firms (some of the following bullet points are adapted from Nazar, 2015):

•There were 23.8 million non-employer firms in 2014.

•Approximately 75 percent of all U.S. businesses are non-employer businesses.

•Of the nearly 24 million non-employer businesses in the United States, over twenty million, that is 86 percent, are individual proprietorships as of 2014.

•Over 1.7 million are partnerships, comprising about 7 percent.

•Almost 1.5 million are corporations, comprising 6 percent. (This includes both C corporations and S corporations, distinctions of tax treatment.)

•To be classified as a “non-employer” business you must have annual business receipts of $1,000 or more and be subject to federal income taxes. (For less than that, you are not considered to have a business.)

•Total revenue of non-employers was over one trillion dollars in 2014.

•Around 80 percent of non-employer businesses for 2014 (over 18 million businesses) reported less than $50,000 in receipts

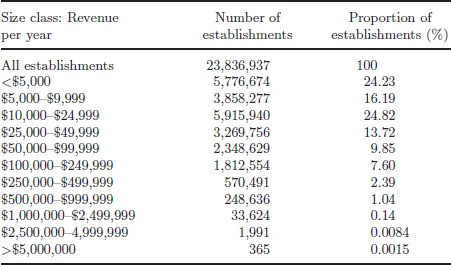

Table 3 below gives some detail on the distribution of sizes of non-employer businesses in 2014, where size, in this case, is annual revenue.

Table 3. Size Distribution of Non-Employer Businesses.

Source: Author’s computations from Bureau of the Census, American FactFinder, https://factfinder.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?pid=NES_2014_00A3&prodType=table, accessed on 3/29/2017.

Who are the proprietors of non-employer businesses? Fairlee and Robb (2007, p. 226) write “A few patterns are beginning to emerge in the young and expanding literature on self-employment. The empirical studies in this literature generally find that self-employment is positively associated with being male, white, older, married, and an immigrant, and with having more education and higher asset levels. Another important determinant that has been identified in the literature is having a self-employed parent.” Relying on their statistical analysis, they argue that it is the experience of working in the parent’s business that provides the key advantage, even though only a very small proportion of the businesses are inherited.

4.Who Are The Proprietors of Small Businesses?

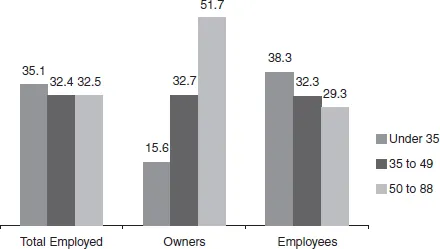

The “demographic” characteristics of small business employers have been studied for some time. The word “demographic” means how they fit in the overall population, that is, for example, are they older? Are they likely to be more or less educated? Headd writes (2013, p. 2) “In 2013, the age makeup of business owners was much older than that of employees. While the proportion of those of prime age in the workforce did not differ between business owners and employees, business owners were much less likely to be younger (under age 35) than employees, 15.6 percent versus 38.3 percent, respectively.” This is illustrated in Figure 1. These data are for all business owners, but they are mostly the owners of small businesses — as we learned earlier in this chapter, small businesses are the huge majority of all businesses — so the data for small business owners could not be very different. The contrast, however, is with the employees of all businesses, and an important proportion of all employees are employed by big businesses.

Figure 1. Ages of Employers and Employees.

Source: Headd (2013).

Further, Headd (2013, pp. 2–3) writes “Business owners were more likely to have a bachelor’s degree or higher education level than employees, 39.2 percent versus 29.2 percent, respectively. In addition, owners were less likely than employees to have a high school degree or less.” Business owners are less likely to be nonwhite, Hispanic or women (Headd, pp. 1–2). “Minority and Hispanic business owners made up less than 15 percent of all U.S. business owners in 2013. Asian business owners represented 4.3 percent of all owners versus 4.8 percent of all private sector employees. Blacks represented 7 percent of all owners compared to 12.1 percent of all employees. Hispanics represented 10.6 percent of all business owners versus 16.7 percent of all employees in 2013. Women’s share of business ownership in 2013 was 35.4 percent of business owners compared to 47.3 percent of private sector employees. . . . This ownership proportion is in line with an Office of Advocacy study which found that 29 percent of U.S. firms were owned by women.” Business owners are also more likely to be married, to own a home and to be veterans. This is shown in summary form in Table 4.

These data are for the United States, but studies for Canada, Britain and Australia, and an international survey by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, suggest that similar patterns will be found in other industrialized countries.

5.The Employees of Small and Medium Employers

Small, medium and large enterprises differ in a number of ways, and there are corresponding differences in the characteristics of their employees. For this section, we will be concerned with enterprises that have from 1 to 500 employees — very-small-, small- and medium-scale employers. If the firm has more than one establishment, employees at all establishments are included. Headd (2000) summarized data from the Bureau of the Census on some of the characteristics of small business employees in the United States, as of 1999. For example, he found that small-business employees were somewhat more likely to be part-time employ...