![]()

Chapter 01 | Water is Chemistry and Physics |

Origins of water

Viewed from space, our planet’s most remarkable feature is its water. It covers around 70% of Earth’s surface, and participates in virtually all meteorological, geological, chemical, and biological processes. Most of us learned about the water cycle in school, but rarely is the question “Where did all the water come from in the first place?” posed. You might think that is a simple question with an established answer. This is not the case. The origins of Earth’s water remain a subject of intense study and debate in the scientific community. Let’s start by going back even further in time — all the way back to the Big Bang. In the moments following the birth of the Universe, primordial particles joined to form considerable amounts of hydrogen, by far the most plentiful element even today. Hydrogen is one of the ingredients that make up water, as we all know from the world’s most famous chemical formula: H2O. Oxygen, the other ingredient, was not created directly from the Big Bang. To find oxygen we have to wind the clock forward a billion or so years to a time when stars populated the universe. Inside the dense, intensely hot cores of stars, light elements like hydrogen and helium fuse together into heavier ones, including oxygen. When a massive star explodes in a supernova, the colossal blast spews these fused elements out into space. When hydrogen and oxygen meet up in interstellar clouds, they merge to form water molecules. So that is, in a sense, where our water came from, and that part is not under dispute. But how did it get from space into our oceans and lakes? Here is where things get less certain.

Our solar system, which formed about nine billion years after the Big Bang, condensed from one such dusty interstellar cloud that certainly contained water. It is reasonable to conclude, then, that Earth’s water has always been on Earth, being a constituent of the materials that originally formed the planet. However, in Earth’s early history, there was not a well-formed atmosphere as we know it today and the surface temperatures were scalding. Any water existing on the surface at that time would most likely have evaporated and escaped into space, so the water we see on Earth today must have been delivered to the surface much later. We can look up for a possible answer: comets and asteroids. Both of these extraterrestrial bodies contain water ice, and many collided with Earth (especially in the young solar system), thereby depositing water onto the planet. As to whether it was asteroids or comets that contributed a greater share, scientists continue to deliberate on that topic. Do comets and/or asteroids answer the question, then? Not necessarily. It is indeed likely that at least some of the water on Earth came via bombardment from space, but there is another option to consider. We can instead look down for a possible answer: deep water. It may be that a vast amount of the water that was present when the Earth formed remained safely trapped inside the planet during those atmosphere-less eons. Earth has an active core that, over geologic time scales, can tectonically exchange materials between the crust and the interior. Perhaps this slow exchange brought water to the surface to form oceans after the planet had cooled sufficiently to maintain a stable atmosphere. Somewhat surprisingly, it is often easier for scientists to probe the chemical makeup of a distant planet than that of our own planetary core. This is because scientists use light and other radiation signals to understand chemical makeup. Such signals can travel through light years of empty space but won’t penetrate from the depths of the Earth’s interior. However, once in a while the deep mantle that is otherwise inaccessible delivers a gift to researchers in the form of rocks expelled through volcanic activity. By studying these specimens and probing subsurface structure through analysis of seismic waves, scientists have found evidence for a shockingly large amount of water buried deep below the surface in a transition zone between the upper and lower mantle — perhaps even several times the total volume of water that we see in our oceans. This water is not free like the water on the surface, but rather it is locked up in the rock itself. No doubt there remains much to learn about the origins of Earth’s water, but water’s mysteries extend beyond just its beginnings.

An anomalous liquid

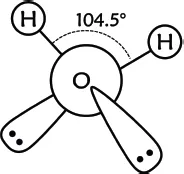

We experience water in various forms every day of our lives. It is the most common and ubiquitous liquid. It is odorless and tasteless. What we smell and taste in water is actually from the presence of other species. Water is so mundane that it seems it could not be less remarkable. On the contrary, despite its apparent ordinariness, water is the most anomalous liquid we encounter. In The Immense Journey, anthropologist and author Loren Eiseley said “If there is magic on this planet, it is contained in water.” Water is undeniably astonishingly bizarre and, surprisingly, still not fully understood. We will get to all sorts of things we do know about water shortly, some of which make clear just how weird water really is, but first let’s take a moment to go over what we don’t know. A single water molecule is not a complicated thing. It is comprised of one oxygen atom and two hydrogen atoms. The geometric arrangement of these atoms is of pivotal importance in determining the properties of water as a material, when lots of molecules come together. The three atoms in a water molecule are not arranged in a straight line, rather, it is bent with both hydrogen atoms sitting on one side of the oxygen atom (Figure 1.1). Many other common molecules form straight lines and do not possess the unique properties of water.

Each hydrogen atom is covalently bonded to the oxygen atom, consuming two of the six electrons available in oxygen’s outer electron shell. The bent structure is a result of oxygen also having two so-called lone pairs of electrons that do not bond to other atoms. The bent structure and the lone pairs make water much more chemically active and interactive than other simple molecules. The covalent bonds and the lone pairs all repel each other, forcing the hydrogen atoms onto the far side of the molecule, forming a bond angle of 104.5°. This structure maximizes the distance between the hydrogen atoms and oxygen’s electron pairs, with each item pointing to the corner of a virtual tetrahedron, a three-dimensional structure with four similar surfaces and corners.

Figure 1.1.Structure of a water molecule.

It is the interactions between these simple water molecules that remains something of a mystery despite over a century of scientific study. There is a complex dance among groups of water molecules, with different molecules coming together and separating in extremely fast fluctuations. The structures of these transient clusters and dynamics of this process are maddeningly challenging to explore even using state-of-the-art characterization instruments and high-level theory. It is quite likely that hidden inside these ephemeral clusters are insights that could transform our understanding of biology, chemistry, geology, and more.

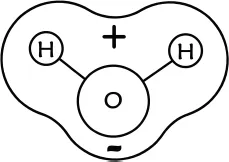

With that in mind, let’s get back to things we understand pretty well when it comes to water. Water’s bent shape has ramifications of importance that is difficult to overstate. Foremost among these is that, because oxygen favors electrons more so than does hydrogen (oxygen is more electronegative), the electron cloud surrounding the molecule is asymmetric. That is, the population of electrons on the oxygen side of the molecule is higher than that on the hydrogen side, leading to a net positive charge in the vicinity of the hydrogens (Figure 1.2) and a net negative charge near the oxygen. The term describing this phenomenon is “polarity,” and it is arguably the most important feature of water.

Figure 1.2.Polarity of a water molecule.

Water is the only substance on Earth that is found naturally in three phases: solid, liquid, and gas. That in itself is a curious fact, but a closer look reveals an even more unusual observation regarding the states of matter for water. Polarity leads to a rare property of water, namely, that solid water (ice) is less dense than liquid water. Upon freezing, the density of water drops nearly 10%. You’ve surely noticed this yourself in that ice cubes float in your beverages. Almost all known materials have the reverse relation. It turns out that the maximum density for water actually occurs at 4 °C. (Under increasing pressure, ice will eventually undergo transitions to other crystalline structures with higher density, but these conditions do not typically exist on Earth — except in Kurt Vonnegut novels.) Ice has a lower density because the molecules arrange themselves into a stable crystalline structure with the polar species orienting to minimize contact between like charges. Ice’s structure consumes a greater volume per unit molecule than those mysterious disordered water clusters present in liquid water. This strange feature is crucial for life. When bodies of water freeze in the winter, ice floats to the surface and provides an insulating barrier allowing the water below to remain liquid throughout the year, thereby sustaining aquatic life in cold climates. If ice did not float, then it would sediment and possibly even remain frozen the next summer. Many bodies of water would slowly freeze over, and the planet would be uninhabitable.

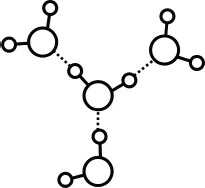

Figure 1.3.Hydrogen bonding.

The interaction between water molecules occurs primarily through so-called hydrogen bonding. A hydrogen bond is an attractive electrostatic force between a hydrogen atom bound to an electronegative atom (such as oxygen) and a second electronegative atom. The hydrogens in water fit this description, and this leads to an attraction between neighboring water molecules (Figure 1.3).

Hydrogen bonds are generally not as strong as covalent bonds, but that does not mean they are not significant. Water, in particular, exhibits rather robust hydrogen bonding. One consequence of water’s hydrogen bonds is that the boiling point of water is higher than one might expect from its mass alone. Normally, lightweight molecules like water are gases at room temperature and pressure, but not water. Intermolecular hydrogen bonding makes it harder for the molecules to separate from one another and enter the gas phase; this allows water to exist in its liquid form on most of our planet. Another consequence of hydrogen bonding is that water is sticky. The technical terms for this stickiness are cohesion and adhesion, with the former describing water’s attraction to water and the latter water’s attraction to other substances. Water’s cohesion is actually the highest among all non-metallic liquids, yet another example of its anomalous nature. Water forms drops so easily thanks to its cohesion. A correlated property is water’s surface tension — also the highest among common liquids. Water molecules sitting at the surface do not have as many neighboring molecules as their brethren buried in the bulk, so these surface molecules cohere more strongly to their neighbors. The surface layer experiences a net inward force, pulled by the molecules below. Therefore, these surface molecules contract a bit, meaning the surface is under tension. Surface tension allows small insects like the water strider and even some amazing lizards to walk or run on water, provides the mechanism by which soap and detergents work (by lowering water’s surface tension), and explains why bubbles are round.

Yet another effect of hydrogen bonding is a phenomenon called capillary action. When water is confined within a narrow tube or porous material, adhesion between water and the walls causes the liquid to rise along the edges. Surface tension acts to maintain an intact surface, resulting in a smooth, curved surface. If the adhesion is stronger than the water’s cohesion, the water will lift upward into the tube or material, stopping only when gravity overcomes these forces. Capillary action is why paper towels wick up fluids so readily, and it allows plants to survive by carrying water through the xylem from the roots up into the limbs and leaves.

Strong hydrogen bonding in water also provides it with a specific heat capacity exceeding that of all common liquids and solids. Heat capacity is a measure of how much the temperature of a material changes upon the addition of a certain amount of heat. A material with a high heat capacity will experience relatively little change in temperature. Since water molecules are strongly attracted to one another, it takes more energy to make them move around. At the molecular level, temperature can be viewed as proportional to the average energy associated with molecular motion, so less motion means lower temperature. Water’s anomalously high heat capacity makes it a good heat storage medium, coolant, and heat shield.

Another anomalous feature of water is its color. Yes, even pure water does have a color, albeit faint and, yes, it’s blue. Bodies of water generally appear to be blue, of course, but that color is in part a product of impurities, in part a result of scattering of light by particulates suspended in the water and density fluctuations, in part reflection of the blue sky above (itself blue because of scattering), and in part because water itself is indeed blue. To see why water’s color is anomalous, we first have to review the origin of color in most common materials. Light from the sun or typical light bulbs contains a full spectrum of colors, evident when it is dissected into a rainbow. When combined all together, these colors become white light. If a transparent material absorbs parts of that spectrum, say the reds, then only the remaining colors will pass through, making it appear blue. (Similarly, if an opaque material absorbs parts of the spectrum and reflects or scatters others, it will appear to be the color of the reflected or scattered light.) Color-generating absorption processes almost always involve the excitation of an electron from a lower energy state to a higher one, an electronic transition, with the color of light absorbed corresponding to the energy difference between these two states. Water, evidently, would not be satisfied with such an ordinary way of creating color. The states for electrons in water do not have levels separated with energies corresponding to visible colors. Vibrations within a water molecule itself, rather, are actually the origin of water’s blue tinge. Oxygen-hydrogen bond vibrations have an energy that corresponds to light having a wavelength of about three microns — that’s in the infrared part of the spectrum, invisible to the human eye. So it also is not simply fundamental excitation of these vibrations that explains the blue color either. It is excitation of higher level vibrations, something that is a rather unlikely event as light passes through water, which results in the blue tinge. These absorptions are so weak, in fact, that it was only in recent years that they have been measured accurately. That’s why your glass of water looks clear and colorless; you need an awful lot of water, like in a large pool or the ocean, before the delicate blue is apparent.

The universal solvent

In addition to all of these extraordinary physical properties of water that result in large part from its polarity, water’s polar nature also makes it a phenomenally effective solvent. That is, water is capable of dissolving a breathtaking variety of different substances; it is, in fact, often called the “universal solvent.” Those materials that are attracted to water (and therefore are likely to dissolve well) are anthropomorphically called “hydrophilic” (water-loving) and those that are not are called “hydrophobic” (water-fearing). When ionic or polar molecules such as acids, salts, sugars, or alcohols encounter water, many water molecules surround them with the negatively charged oxygen sides of water attracting the positively charged components of the solute and the positively charged hydrogen sides attracting the negative components. Dissolved molecules are therefore said to be “hydrated” by a shell of water molecules. It is even possible to get small amounts of some non-polar substances such as carbon dioxide or gasoline to dissolve in water via a process where water either induces mild polarity in the solute or there is a gain in entropy (greater dispersal of the solute molecules relative to the pure materials) from the dissolution process. Since the Big Bang, nature strives to increase entropy. Water’s unique ability to dissolve so many different substances is critical for life. Our bodies, like those of all living things, contain many thousands of different chemicals — each solvated in water. Wherever water goes, whether through the soil and rocks, through our bodies, or through the atmosphere, it grabs other substances and takes them along for the ride. Such action carries valuable minerals and nutrients to sustain life and reshape the world around us, but it has an unfortunate flip side — water is also extremely easy to pollute.

Let’s take a look at some examples of the universal solvent in action and its central importance. One of the non-polar substances that can dissolve in water, although only in relatively low concentrations (just a few milligrams per liter), is oxygen (O2). Many organisms living in the water depend on this dissolved oxygen (DO) to breathe. There is a delicate balance in aquatic environments where various dissolved substances can promote or hinder different species. Too many nutrients in the water from agricultural runoff or sewage can spur the growth of algal or phytoplankton blooms, which consume DO and create eutrophic condition...