![]()

Part I

Biographical Perspectives

![]()

1

Odysseys in China Watching: Comparative Look at the Philippines and Nepal

Tina S. Clemente

Asian Center, University of the Philippines Diliman, Philippines

Pamela G. Combinido

Independent Scholar

This chapter attempts to accomplish three objectives. The first objective is to explore an oral history comparison that goes beyond the usual geopolitical boundaries. It is usual for the Philippine context to be compared with that of another country within Southeast Asia owing to the similar experiences of overseas, diasporic, or transnational Chinese and the issues that relate to the region’s relationship with China. The second objective is to problematize the idea that oral histories on China knowledge are not hinged on essentialism. The notion that China knowledge may be less valid owing to the absence of essential elements such as classical Sinology and language proficiency deserves some rethinking. The third objective is to explore the concept that such a comparison underscores that flexible epistemological approaches can build the field of China studies.

Section 2 casts attention on dissecting the evolution of thinking of Santa Romana and Pandey, bringing to light the salient points of inflection in their odysseys. Section 3 focuses on how a deep interest in China elucidates the thinkers’ positioning of their perceptions on China. In closing, the chapter argues how the comparative insights fill a gap, enriching the field of China studies.

Comparison of Intellectual Trajectories

We trace paths of China watching through parallel comparison of experiences, retrieved through oral history interview. Through parallel comparison of Santa Romana’s and Pandey’s transcripts, we generate insights into the linkages between the intellectuals and their China watching, considering the exercise of agency during the interplay of external socio-historical factors and their internal motivations. Drawing inspiration from Mallard’s (2014) paired biographies approach, we embark on content analysis that aids in teasing out the internal deliberation by both intellectuals in their China watching. In a sense, akin to Mallard (2014), the problematique of this chapter, that is China watching is parametrized by particular contexts, is intrinsically borne of comparison, or as Mallard puts it, conceptually relational. Also, we avoid the issues on inter-subjectivities that Boyd (2015) raises, given that we allow the intellectual’s subjectivity as a fundamental assumption in their storytelling to aid in our understanding of the nature of their China watching.

Giving importance to individual stories, Thomas Carlyle and Ralph Waldo Emerson viewed history in parallel fashion (Boorstin 1998). The former saw history as the “essence of innumerable biographies” (Carlyle 1852: 220) while the latter saw history as subjective, arguing that “there is properly no history; only biography” (Emerson 1841/1886: 40). In venturing into intellectual history, we go further by scrutinizing the journeys behind the ideas of the thinkers as these provide a better understanding of the internal negotiations that were instrumental in refining the thinkers’ ideas and their identity as thinkers. Buchholz (2007) underscores this in his study of the celebrated economist, John Stuart Mill. While Mill is known for doing landmark work on enhancing utilitarianism, the achievement did not come without Mill going through an existential crisis at 20 years of age, wasting away in rationalism but later regenerating as a romantic — the messy internal negotiations registered as inflections in thinking. In his autobiography, Mill laments:

On a similar note, Bangladeshi intellectual and Nobel Laureate, Muhammad Yunus, recounts his journey as an economist and attributes part of his transformation to experiential learning through immersion among the poor, whose economic plight he studied. Yunus relates,

Yunus articulates an important vantage point of his intellectual transformation:

We consider affective memory as the unit of analysis of this study on comparative intellectual history (Havel 2005). Thinkers recollect myriad of experiences in the course of articulating their oral history, but only those experiences that are emotionally encoded become significant units in the evolution of their thinking. The lived experience of individuals as manifested in personal affective memory, by definition and ontology, is central to public memory (Havel 2005). The perspective on affective memory in this chapter is informed by the caveats embedded in the intertwined web of emotion, experience, and identity and how social concerns tend to be seen as determined by an overemphasis on personal emotion. We thus recognize that the various mechanisms through which meaning is constructed also constitute their own narratives that are internalized in the intellectual’s deliberation of his experiences. Identity, which is a “coherent sense of self over time” (Harding 2014: 99) and experience then, while elements in articulating one’s narrative, are also outcomes of the narrative (Harding 2014).

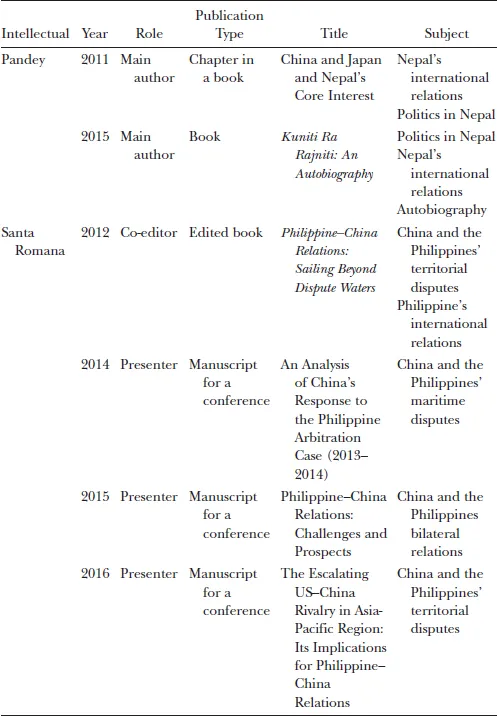

Table 1 provides a brief academic and professional background of Chito Santa Romana and Ramesh Nath Pandey. Journalism played a significant role in the background of both Santa Romana and Pandey. Santa Romana had a long career as a journalist in China before becoming a Philippine-based public intellectual while Pandey was a journalist prior to his long career as a political figure, minister, and senior diplomat in Nepal.

Table 1. Professional Background

Aside from his media commentaries on issues about China–Philippines bilateral relations, Santa Romana engaged with the academe in the Philippines through symposia, conferences, and similar events. His work focused on the foreign relations issues between the Philippines and China, and particularly the maritime dispute. Pandey, on the one hand, published commentaries in newspapers in Nepal and India. He recently published his book, which details his involvement in Nepal’s politics and its relations with other countries. He also wrote a chapter in a book edited by his son, Nishchal Nath Pandey. Table 2 lists selected scholarly works of these thinkers, which centered on the dynamics of bilateral relations with China.

Table 2. Selected Scholarly Work

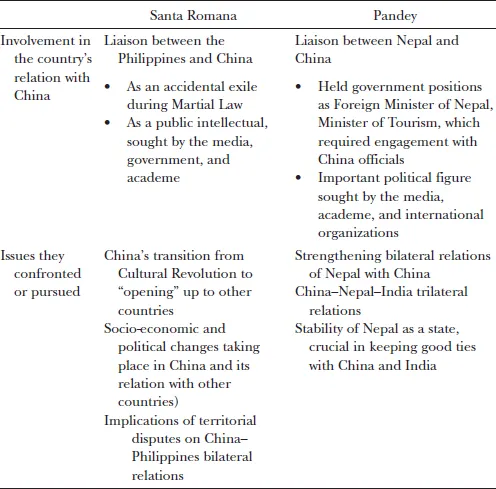

Santa Romana and Pandey are important figures in their respective countries for their public discussions about bilateral relations with China. Santa Romana became a China “expert” owing to his many years of experience in China as an accidental exile and as a respected broadcast journalist. Pandey, on the other hand, held several government positions that gave him leeway in directly dealing with Chinese counterparts on bilateral projects that had material outcomes for Nepal. Table 3 presents both thinkers’ roles in bilateral dealings with China.

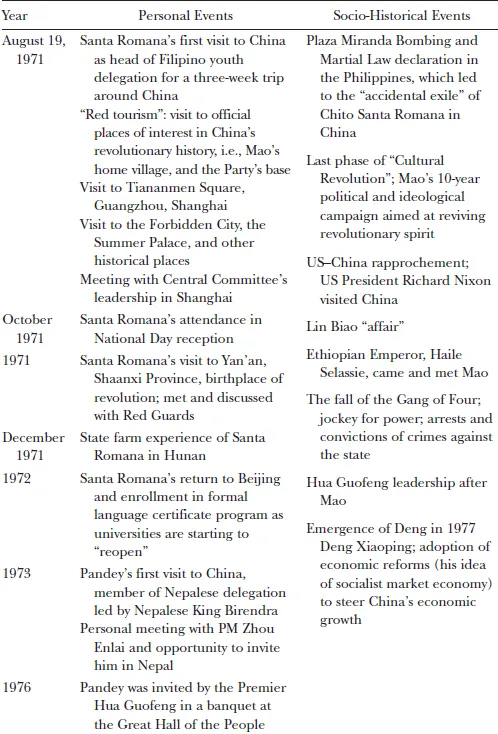

As part of our attempt to grapple with the history–biography connection (Mills 1959), we trace the goings-on of the intellectuals by looking at their “lives processually in the context of the society they live in” (Brannen and Nielsen 2011: 609). As presented in Table 4, the content analysis framework paid attention to significant personal events that the intellectuals keep going back to in the interview transcripts. Personal events here are happenings they directly witnessed due to their interaction with China. Socio-historical events are the incidences related to history and politics and development of China which they related to their personal experience.

Table 3. Intellectuals’ Key Roles in Country’s Engagement with China

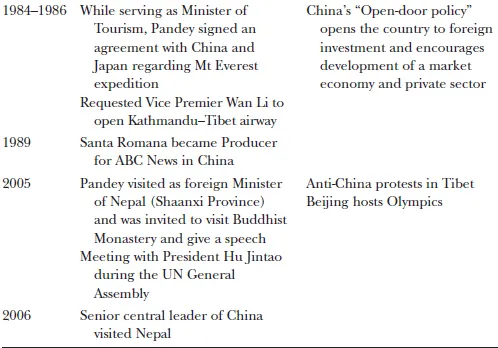

Table 5 summarizes the inflections in perspectives about understanding China. The perspective of China watching is shaped by the experiences, lessons, and hope for the prospects of China. The perspective changed over time as they directly experienced China and contemplated about future directions.

Studying China and Positioning as a China Watcher

Recollecting one’s China watching brings to view a confluence of circumstances in the macroenvironment, one’s particularities as a thinker, and the kind of role that one ascribes to oneself in studying China. In this section, we use the elements teased out in the previous section and focus on four major areas of the thinkers’ lens in studying China and their internal and external negotiation in positioning themselves as a China watcher. In all the subsections, we consider the thinkers’ positioning across gradations of affinity, objectivism, and balance regarding China as we posit no absolute boundaries in these categories. In this sense, we go beyond the ontological discomfiture in the objectivism vs. relativism discursive crevasse (McCourt 2007; Bernstein 1983). We first look at the motivations that began their interest in China, the experiment of direct experience, reflections on witnessed change, and opinions on the prospects of China.

Initial Impressions and Contact

For Santa Romana, it was the anti-martial law activism during the Marcos years that began his interest in China. He was an activist during his university days in De La Salle University and was also the president of the student council and a part of the student paper. His active involvement in the national student union, national college editors’ guild, and graduate studies at the University of the Philippines — the bastion of student activism — deepened his activism. Santa Romana, in his visit to the US, saw how student activism was a force that opposed the Vietnam War. But China got him hooked. The Cultural Revolution demonstrated student power and the Red Guards projected the expression of that power in his mind while his involvement in the leftist movement created an ideological affinity. Santa Romana started reading about China and Maoism and wanted to know about what the Philippines could learn.

Table 4. Biography–History Nexus in Intellectuals’ China Watching

In Pandey’s case, interest comes from what he sees as a national environment that is generally interested in China, a setting where it is usual for Nepalese to follow goings-on in China. As a journalist, he also found himself featuring China in his work. He recounts the anticipation he felt on seeing China for the first time, which he had only known from what he had read in dailies and books until then. As he traversed to “No Man’s Land,” crossing from Hong Kong to China in five minutes, what greeted him was the sight of the Chinese who had no gender distinction in the same gray garb and hairstyle that they wore.

Table 5. Evolution of Thinking about China

Experiment of Experience

The thinkers depict China in varied ways. While both relate contentious accounts, Santa Romana depicts them with an investigative, analytical eye while Pandey renders them positively. This demonstrates that one’s subjective perspective determines the interpretation of an experience and, likewise, it determines the knowledge that one forms about the experience (Nietzsche 1989: 12).

Santa Romana believed that “[d]irect experience teaches people” (Santa Romana 2016: 12). The experiment of experience led to discoveries of internal socio-political struggles in China. Santa Romana was able to capture the social climate in China at that time that the country was not open to outsider scrutiny. He had to learn to hear between the lines as bu qingchu (not clear) was a common response to deflect questions. Trying to understand was “almost like the art of reading tea leaves” (Santa Romana 2016: 3, 13).

Santa Romana was puzzled by the “formal protocol” set by the host team as a way of organizing the delegation hierarchically. In the first trips, Santa Romana felt uneasy that he had to ride a different vehicle because they wanted to separate the senior members from the rest of the delegation. “It was actually hierarchical when we were expecting it to be egalitarian,” Santa Romana recalled (2016: 4–5). Then he narrated how they were treated better than the ordinary Chinese. In trains, they rode first class. They would be given delicacies as compared to the ration given to ordinary Chinese. They experienced being mobbed by Chinese locals who were amazed at how different they seemed. In response to the protectiveness of the host...